The Struggle for Women’s Rights Begins

In Colonial America and the first few decades of the new United States, individual women often fought for equal rights for themselves, such as assuming business interests of a husband after his death. During the war for independence women did their part by supporting the Patriots in numerous ways, including organizing boycotts of British goods.

In Colonial America and the first few decades of the new United States, individual women often fought for equal rights for themselves, such as assuming business interests of a husband after his death. During the war for independence women did their part by supporting the Patriots in numerous ways, including organizing boycotts of British goods.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, American law was based upon English common law and the doctrine of coverture, which stated that a woman’s legal rights were incorporated into those of her husband when she married, and she was not recognized as having rights and obligations distinct from those of her husband. One of the few legal advantages of marriage for a woman was that her husband was obligated to support her and be responsible for her debts.

The ownership of a woman’s real and personal property passed to her husband the moment she said, “I do.” Furthermore, a husband could do anything he wished with his wife’s material possessions. He could sell them, give them away or simply destroy them, while a wife was forbidden to convey (sell, give or will) her own property.

A Married Woman’s Legal Rights in Antebellum America

• She could not control property that was hers before the marriage.

• She could not keep or control the wages she earned.

• She could not acquire property while married.

• She could not transfer or sell property.

• She could not bring any lawsuit.

• She could not make a contract.

Technically, a husband could do anything he wished with his wife’s material possessions. He could sell them, give them away or simply destroy them, while a wife was forbidden to convey (sell, give or will) her own property. How strictly this was adhered to depended upon the couple. Each was different and, decision-making was shared to varying degrees.

Over the course of the 19th century, however, women’s demands for equal rights began to change from a series of isolated incidents to an organized movement, but for years it was far from unified. Enormous changes swept across the United States as we changed from an agrarian society to an industrialized one.

Beginning in the 1820s, single young women began to work in the textile mills that opened in New England, where they often lived in boarding houses owned by their employers – a totally new concept. Middle-class women were increasingly confined to the dreaded domestic sphere, where she created a haven for her hardworking husband and raised her children.

However, the changes in women’s lives allowed them to begin to act politically, for themselves and for others. Women began working in the abolitionist movement and in the process became organizers and leaders, and found their own voices. Over time, they began to realize that their own legal and political rights had been neglected.

First Women’s Rights Convention

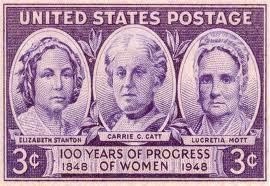

The abolitionist movement was a critical first step in the creation of an organized movement for the rights of women. The seed for the first Women’s Rights Convention was planted in 1840, when social reformers and abolitionists Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton met at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, England. Stanton was the young bride of antislavery agent Henry Stanton, and Mott was a Quaker preacher and a veteran of reform movements.

The two women became allies when the male delegates attending the convention voted that women should be denied participation in the proceedings because of their gender. They talked then of calling a convention in the United States to address the condition of women. Eight years later, it came about as a spontaneous event.

After Quaker service on Sunday July 9, 1848, a social visit brought Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott together again. Mott was visiting her sister Martha Coffin Wright in Auburn, New York, and Stanton was then living in nearby Seneca Falls. Stanton, Mott and Wright joined Mary Ann McClintock and Jane Hunt for tea at the Hunt home in nearby Waterloo. All except Stanton were Quakers, a sect that afforded women some measure of equality, and all five were well acquainted with the anti-slavery and temperance movements.

Fresh in their minds was the April passage of the long-deliberated New York Married Woman’s Property Rights Act, a significant but far from comprehensive piece of legislation. The time had come, Stanton argued, for women’s wrongs to be laid before the public, and women themselves must shoulder the responsibility. Before the afternoon was out, the women decided on a call for a convention “to discuss the social, civil and religious condition and rights of woman.”

Using the Declaration of Independence as her guide, Stanton wrote the Declaration of Sentiments, in which she stated that “all men and women had been created equal” and went on to list eighteen “injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman.” This document was presented at the first Women’s Rights Convention on July 19 and 20 at the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Seneca Falls.

A crowd of about three hundred people, including forty men, attended the convention. Since none of the women felt capable of presiding over the meeting, Lucretia’s husband James Mott did the honors. Every resolution in the Declaration of Sentiments passed unanimously except women’s suffrage (the right to vote).

The eloquent Frederick Douglass, a former slave and editor of the Rochester North Star, however, swayed the gathering into agreeing to that resolution as well. At the closing session, Lucretia Mott called for “the overthrowing of the monopoly of the pulpit, and for the securing to woman equal participation with men in the various trades, professions and commerce.” The Seneca Falls Declaration was signed by 100 women and men, but subsequent criticism caused some of them to withdraw their names.

The proceedings in Seneca Falls, followed a few days later by a meeting in Rochester, brought forth a torrent of sarcasm and ridicule from the press and pulpit. Noted Frederick Douglass in the North Star:

A discussion of the rights of animals would be regarded with far more complacency by many of what are called the wise and the good of our land, than would be a discussion of the rights of woman.

Although somewhat discomforted by the widespread misrepresentation, Elizabeth Cady Stanton understood the value of attention in the press. “Just what I wanted,” Stanton said when the New York Herald printed the entire text of the Declaration of Sentiments, calling it amusing. She wrote:

Imagine the publicity given to our ideas by thus appearing in a widely circulated sheet like the Herald. It will start women thinking, and men too; and when men and women think about a new question, the first step in progress is taken.

When the members of the American Anti-Slavery Society in Boston met in 1850, they decided to create a national women’s rights convention. For the next ten years (except 1857), delegates met at National Women’s Rights Conventions, where a wide range of issues were discussed including educational rights, equal pay for equal work, marriage reform and women’s property rights. Stanton, then only thirty-two years old, went gray for the cause, seemingly overnight.

National Women’s Rights Conventions were not held during the Civil War years (1861-1865). Instead women activists focused their energies on the abolition of slavery and supporting the Union war effort. At the 1866 meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in Boston, Lucy Stone and Susan B. Anthony suggested that women and African Americans establish an organization which would work toward universal suffrage.

That same year, the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) (also known as the Equal Rights Association) was founded by activists Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Frederick Douglass. The 15th Amendment, proposed by the U.S. Congress on February 26, 1869, would grant voting rights for African American men. It did not extend voting rights to women of any color.

This caused a rift among AERA members – some considered it a victory, while many women activists were very disappointed. In 1869, Stanton and Anthony established the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) whose sole mission was to win voting rights for women. Abolitionists like Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell and Julia Ward Howe believed that suffrage for women and blacks should remain linked. Therefore, they created a new organization – the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

During the ensuing years, African American women also created their own reform movements, and women like Sojourner Truth represented an important link between these organizations. For years, these organizations worked side-by-side for equal rights for all women. However, it soon became clear that securing the right to vote for women would require a united effort.

In 1890 the NWSA and AWSA united as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). When victory finally came in 1920, seventy-two years after the first convention for women’s rights, only one signer of the Seneca Falls Declaration – Charlotte Woodward – had lived long enough to cast her ballot.

Timeline of Significant Events in the Women’s Rights Movement:

• 1850

The first National Women’s Rights Convention was held at Worcester, Massachusetts, attracting more than 1,000 participants. Paulina Wright Davis, Abby Kelley, William Lloyd Garrison, Lucy Stone and Sojourner Truth attended.

• 1851

The second National Women’s Rights Convention was held again in Worcester, Massachusetts. Participants included Horace Mann, New York Tribune columnist Elizabeth Oakes Smith and Reverend Henry Ward Beecher.

• 1853

Women delegates Antoinette Brown Blackwell and Susan B. Anthony were not allowed to speak at The World’s Temperance Convention held in New York City.

• 1853

The Una premiered in Providence, Rhode Island, edited by Paulina Wright Davis. With a masthead declaring it to be “A Paper Devoted to the Elevation of Woman,” it was acknowledged as the first feminist newspaper.

• 1866

The 14th Amendment was passed by Congress (ratified by the states in 1868), the first time “citizens” and “voters” are defined as “male” in the Constitution.

• 1866

The American Equal Rights Association was founded, the first organization in the United States to advocate women’s suffrage.

• 1868

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan Anthony began publishing The Revolution, one of the most important radical periodicals of the women’s rights movement. Its motto: “Men, their rights and nothing more; women, their rights and nothing less!”

• 1869

Women in Wyoming became the first to vote following the granting of territorial status. For the first time in the history of jurisprudence, Wyoming also allowed women to serve on juries and had the first woman court bailiff and justice of the peace (1870).

• 1870

Iowa became the first state to admit a woman to the bar: Arabella Mansfield.

• 1870

The 15th Amendment received final ratification. By its text, women were not specifically excluded from the vote. During the next two years, approximately 150 women attempted to vote in almost a dozen different jurisdictions from Delaware to California.

• 1872

Through the efforts of woman lawyer Belva Lockwood, Congress passed a law giving women federal employees equal pay for equal work.

• 1872

Howard University law school graduate Charlotte Ray, the first African American woman lawyer, also became the first woman permitted to argue cases before the U.S. Supreme Court

• 1873

Myra Bradwell applied for admission to the Illinois bar, but the state supreme court denied her admission because she was a woman, noting that the “strife” of the bar would surely destroy femininity. In Bradwell v. Illinois, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that states could restrict women from the practice of any profession to uphold the law of the Creator.

• 1873

The Comstock Act of 1873, was a federal law which made it illegal to send any “obscene” materials through the mail, including contraceptive devices and banned the distribution of information on abortion for educational purposes. Twenty-four states passed similar prohibitions. These state and federal restrictions are collectively known as the Comstock laws.

• 1877

Helen Magill is the first woman to receive a Ph.D. at a school in the United States, a doctorate in Greek from Boston University.

SOURCES

The Little Meeting at Seneca Falls that Changed the World

Gale Encyclopedia of US History: Women’s Rights Movement

Sewall-Belmont House and Museum: Women’s History in the U.S.