Two Women Diarists Tell the Story

The Battle of Baton Rouge might have been considered small or insignificant by Civil War standards, but to the women who lived in that city, it was traumatic. Twice they were forced to flee from their homes when Union gunboats in the Mississippi River shelled their town.

The Battle of Baton Rouge might have been considered small or insignificant by Civil War standards, but to the women who lived in that city, it was traumatic. Twice they were forced to flee from their homes when Union gunboats in the Mississippi River shelled their town.

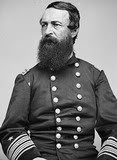

Image: Civilians, including a young girl in the foreground, survey damage in Baton Rouge after the battle there in August 1862.

Backstory

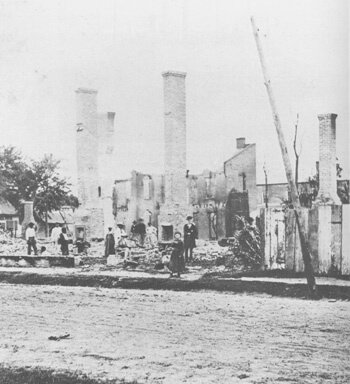

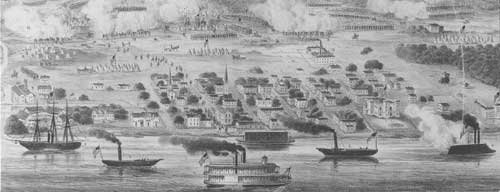

The Union Navy captured Baton Rouge in May 1862, meeting little resistance as the state government fled to Opelousas, about 60 miles west, and later to Shreveport. A few weeks later, when Confederate guerrillas fired on Union sailors rowing ashore to get their laundry done, fleet commander Admiral David Farragut bombarded the city.

In the spring of 1862 the Union Navy sailed up the Mississippi intent on capturing Baton Rouge.

On May 28, three weeks after Federal forces took control of the capital, five of Admiral David Farragut’s men set off for the riverbank in a small unarmed boat in search of a woman to do their laundry.

A band of Confederate guerrillas fired on the sailors as they neared the shore. Two U.S. gunboats returned fire, destroying several waterfront homes and accidentally killing three women. In his diary, Baton Rouge planter John C. Elder recorded that he had seen women running for safety as the attack got underway. He gave his buggy to two of them, one coddling a newborn baby in her arms, to help them escape.

A number of buildings were destroyed and many more were damaged, including the Capitol and St. Joseph’s Catholic Church. Sarah Morgan Dawson, a young woman of twenty who lived in Baton Rouge, fled the city with many others when the shells began to fall. She later described the mass exodus in her diary:

It was a heartrending scene. Women searching for their babies along the road, where they had been lost, others sitting in the dust crying and wringing their hands, for by this time, we had not an idea but what Baton Rouge was either in ashes, or being plundered, and we had saved nothing.

After Farragut’s bombardment ceased, General Thomas Williams landed 2,600 Union soldiers and occupied the city, and the people of Baton Rouge came to respect General Williams because he sometimes provided armed guards to protect private homes from looters. On the other hand, Williams treated his own men cruelly. It was said that the soldiers got even by digging hidden pits around town so Williams would fall into them when he made inspections.

In the summer of 1862, Confederate General Earl Van Dorn came to the conclusion that re-taking Baton Rouge would be key to driving Union forces out of Louisiana, by launching attacks on Union occupied territory and threatening Union control of New Orleans. The Confederate ironclad ram Arkansas had come down the Yazoo River, inflicting damage on the unprepared Union fleet as she passed, and was anchored in Vicksburg.

Battle of Baton Rouge

The summer in occupied Baton Rouge had passed uneventfully, until early August, when Confederates tried to recapture the capital city. General John C. Breckinridge (US vice president under James Buchanan) took a small army from Camp Moore to attack the city from the east. At the same time, the Confederate gunboat Arkansas was to steam down the Mississippi and attack the Union ships in the river. If all went well for the rebels, General Williams and his Yankees would be crushed between them.

On the foggy morning of August 5, 1862, Breckinridge attacked and began pushing the enemy back toward the river. General Ben Hardin Helm, brother-in-law of Mary Todd Lincoln, was one of the first Confederates to fall. Before daylight two units mistakenly fired on each other, and Helm suffered a crushed leg when his horse reared and fell on top of him. He later died of his injuries.

Then, Union gunboats in the river began shelling the Confederate forces. The Arkansas could have neutralized the Union gunboats, but her engines failed and was unable to participate in the battle. Federal land forces, in the meantime, fell back to a more defensible line, and Union commander General Thomas Williams, was killed soon after.

The new commander, Colonel Thomas W. Cahill, ordered a retreat to a prepared defensive line near the river and within the gunboats’ protection. Rebels assaulted the new line, but with the help of three gunboats, Union troops forced Breckinridge to retreat.

Image: A Lithograph Depicting the Battle of Baton Rouge

Image: A Lithograph Depicting the Battle of Baton Rouge

When the Arkansas crew was unable to restart the ship’s engines the following day, they decided to destroy the vessel rather than allow the enemy to capture it. The men set fire to the ironclad, set it adrift in the river and scrambled ashore. When the fires reached the powder magazine, the Arkansas exploded and sank.

Diarist Sarah Morgan Dawson witnessed the burning of the Arkansas:

I had no words or tears; I could only look at our sole hope burning, going, and pray silently. O it was so sad! Think it was our sole dependence! And we five girls looked at her as the smoke rolled over her, watched the flames burst from her decks, and the shells as they exploded one by one beneath the water, coming up in jets of steam. And we watched until down the road we saw crowds of men toiling along towards us. Then we knew they were those who had escaped [the Arkansas], and the girls sent up a shriek of pity. On they came, dirty, half dressed, some with only their guns, a few with bundles and knapsacks on their backs, grimy and tired…

Approximately a third of the city of Baton Rouge was destroyed in the battle, largely because Union soldiers burned or knocked down nearly all of the houses and buildings close to the river to give their gunboats a clear field of fire. But the city’s troubles were not over. Before leaving the city on August 21, the Federals went on a looting and burning spree that destroyed more of the town.

Later that day, the Union ground troops boarded transports and went back down the river to Carrollton, just above New Orleans. The gunboats Essex and No. 7 remained at Baton Rouge, and their commanders threatened to shell the town if Confederate troops returned. Union forces returned in December, burned down the Capitol, and remained in the Baton Rouge area for the rest of the war.

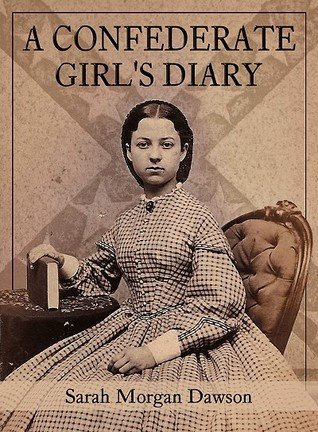

Sarah Morgan Dawson

Nineteenth-century writer, Dawson is best known for the diary she kept during the Civil War (March 1862 through April 1865), in which she chronicled her thoughts and experiences, providing one of the most detailed accounts of civilian life in wartime Louisiana. Living in Baton Rouge with her mother and sisters, with all their menfolk already deceased or fighting in the Confederate Army, Dawson recorded the scarcity of food and household items as a result of the Union blockade.

When the Federal onslaught on Baton Rouge began in earnest, Dawson kept her running bag packed and her personal papers ready to burn. Within days of the Battle of Baton Rouge, Sarah, her mother and her sisters, Miriam and Eliza, abandoned their home for safer quarters in Clinton. Inhabiting a sparsely furnished one-bedroom apartment, Dawson documented the hardships of refugee life.

The federal assault on the Confederate stronghold at Port Hudson in July 1863 forced the Morgan women to make a final exodus to occupied New Orleans, where they joined the household of Dawson’s half-brother and Unionist sympathizer Judge Philip Hicky Morgan. While in his home, Dawson received news of the death of her brothers, Gibbes and George, in February 1864.

Without an independent fortune, Dawson spent the late 1860s as a dependent in Philip Morgan’s household. In May 1872, Dawson and her mother moved to South Carolina to make their home with Sarah’s younger brother, James. In an effort to support herself, Dawson accepted an editorial position at the Charleston News and Courier, for which she wrote a series of editorials on the plight of young, single women in the postwar South.

Eliza McHatton Ripley

Eliza Chinn had married James Alexander McHatton in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1852, and for ten years thereafter they lived at Arlington plantation on the Mississippi, four miles below Baton Rouge. On the morning of August 5, 1862, Eliza Ripley witnessed hundreds of women pouring out of the town, having been roused from their beds by gunfire, and gave a vivid description of the scene:

So, that morning, standing alone at my window, watching through the dim mist what seemed to be the ebb and flow of battle, hearing in the distance the booming, hissing and rattling sounds of conflict, I never once thought of the homes of that besieged city, of the women and children, the old men and the sick, never once thought of them, so swallowed up the destiny of the day every other consideration.

But when that struggling mass was revealed to me, pouring, panting, rushing tumultuously down the hot, dusty road, hatless, bonnetless, some with stockings and no slippers, some with wrappers hastily thrown over nightgowns… men trundling children too young to run, in dirty wheelbarrows, while other little half-clad, barefooted ones ran beside, weary and crying; an old man who could scarcely totter along, bearing a baby in his trembling arms, while the distracted mother carried an older child with wounded and bleeding feet…

Some ran, some stumbled along, others faltered and almost gave out; but before I could hurry on my clothes they poured into our gates and invaded the house, a small army of them, about five hundred tired, exhausted, broken-down, sick, frightened, terrified human beings… no turning back; on – on – through yards and over fences and down narrow, dusty lanes – anywhere to get away from the clash of steel and the bursting of countless bombs!

The battle roared and surged, but there was a roaring and surging battle for bread in that house which for the moment silenced every other. Our store-closets were thrown wide open; but how the crowd managed that day I never knew. Before noon news came of our defeat. I was sick and heart-sore, too much so to eat my own slender breakfast which Charlotte smuggled up the back stairs under her apron; too sick to care, too overwhelmed with the immensity of the undertaking of feeding a great multitude with five loaves and no fishes….

The few men in the army that invaded Arlington foraged as better-disciplined ones do, and brought in some sheep and an ox; killed, skinned, and cut them up with such knives as they could find, and in lieu of better, used their own pocket-knives. Bits of meat distributed around hastily cooked, smoked, and singed, they devoured like savages… Long before noon the twelve pounds of tea from the store-closets had entirely disappeared.

The brief conflict was over. We knew we were beaten; the bad news followed swiftly after the defeat; but the news of our dear ones, the anxiety to know particulars… but, above all, the overwhelming news that we were beaten, wore us all out. About sunset a sergeant and a few men from the victorious enemy came down to Arlington and demanded to see my husband. Of course, he was not at home, and I received them, bewitched to know what to say, for I could not tell them that he was with General Breckinridge’s wounded.

I made the most plausible excuse possible for his temporary absence, and the sergeant handed me a permit for him to enter their lines and visit General Clark of Mississippi, a most dear friend, who had been grievously wounded and was their prisoner. My husband returned before bedtime, and hurriedly availed himself of the permit. In his absence word came to me… that the Federal officer in command said, if we did not send that rebel crowd away from Arlington, a gunboat should be dispatched to shell them out. I was desperate then, and simply replied that I could not send that homeless multitude adrift.

Many became alarmed, however, and took up their weary march, some going down to neighboring plantations on the river-bank, and others going back into the woods and swamps; enough remained, however, to overflow the house – every stair-step had its reclining form, every inch of sofa, bed, and floor was occupied by tired, sleepy humanity…

At that time, Eliza Ripley had a small child and a baby only two-weeks-old, and she was caught in a desperate situation, made worse when Federal authorities made good their threat.

A hissing noise rent the air, and a bomb exploded in front of the house; then another, and another; and a fourth went whizzing over our heads, exploding with loud reports back of the house, and on this side and on that. A gunboat anchored in the river was sending its deadly missives far and wide…

Each bomb called forth wails and shrieks of terror from the thoroughly alarmed and nervously excited people. After having accomplished their purpose, the boat moved off; but there was no more roosting that night, nor sleeping either. A feeling that something more was to happen pervaded the air, and we sat about in anxious groups and desperately waited for it.

The first slanting rays of the rising sun saw a good many tired fathers and mothers march off with their little half-clad families in various directions. Others wandered back to their demolished and desecrated homes, or to the homes of friends in the country; and by noon none were left to our hospitable care, except the mothers with the new babies.

The poor woman with the sick child was frightened by the mere threat of bombardment; she picked up the scarlet fever and blanket [?], there seemed little else tangible – the patient was so emaciated and lifeless – and sought refuge in the woods. I would add here that the child is alive to-day, a beautiful woman, so deaf from that illness and cruel exposure that she has almost lost her speech.

Shortly after the Battle of Baton Rouge, Eliza’s husband fled to avoid arrest for having removed some of his slaves in defiance of the orders of the Federal general, narrowly escaping the approach of the Union Army. Thus he left Eliza to follow him with a carriage, and a wagon carrying their belongings, a duty which proved both difficult and dangerous.

Eliza, James and a small caravan traveled with cotton and supplies through Texas into Mexico, and remained there until the war ended, and then sailed for Cuba in 1865. There, they ran a sugar plantation, using the southern antebellum model with which they were familiar, and joined the highest social circles.

The Battle of Baton Rouge Commemorative Ceremony is held every year on the first Saturday in August in and around Magnolia Cemetery, sponsored by the Foundation for Historical Louisiana.

SOURCES

Sarah Morgan Dawson by Giselle Roberts

The Battle of Baton Rouge