Wives of Generals Killed at Gettysburg

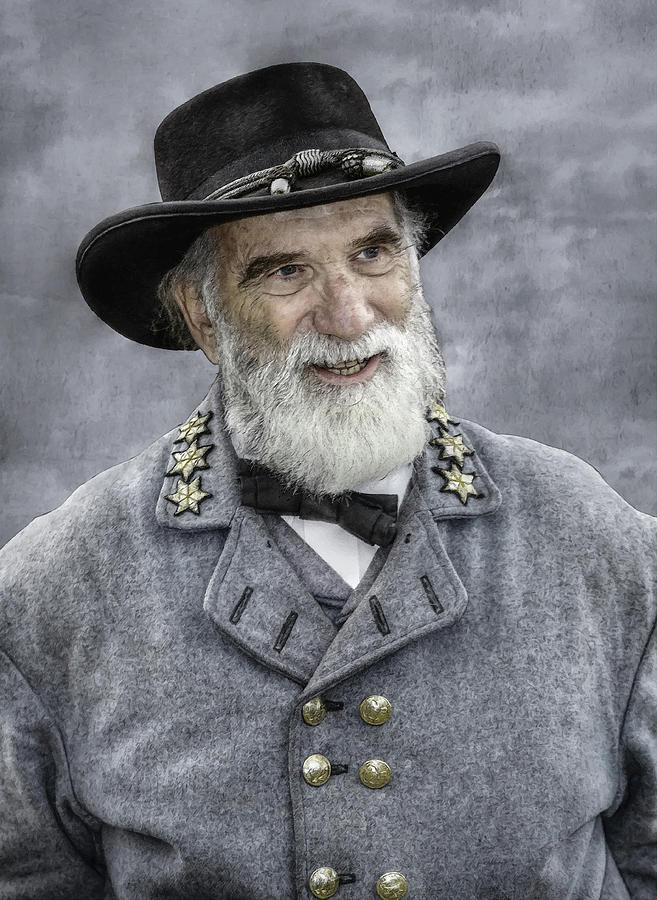

Image: Barksdale’s Charge by Don Troiani

Confederate General William Barksdale – his hat off, his long white hair blowing in the wind – led his Mississippi brigade into battle to break the Union Line on the afternoon of July 2, 1863 at Gettysburg. This action would forever after be known as the grandest charge ever made by mortal man.

Narcissa Saunders Barksdale and the General’s Dog

William Barksdale, senator turned general, originally from Tennessee, moved to Mississippi as a young man, and settled near Columbus, where he studied law and was admitted to the bar. In 1849 Barksdale married Narcissa Saunders, who brought twenty slaves, horses, mules, and several wagon loads of household goods to the marriage. By 1860 Barksdale owned thirty-six slaves, a plantation, and several small farms.

General William Barksdale and his men arrived at Gettysburg in the early morning hours of July 2, 1863. General Robert E. Lee‘s plan for the second day of the battle was to have General James Longstreet‘s Corps advance up the Emmitsburg Road and attack the thin Union left. Late in the day, Barksdale’s brigade of Mississippians stood ready to attack.

When word finally came to advance, the gallant Barksdale galloped to the front of his brigade and personally led the charge. A veteran later recalled that they ran “yelling at the top of their voices, without firing a shot,” and “sped swiftly across the field.” A Union colonel who witnessed the charge called it the “grandest charge ever made by mortal man.”

In this grand charge, General Barksdale rode at the head of his troops, with his hat off and his long white hair blowing in the wind. For a moment, they pierced the Union line, until reinforcements arrived to block them. Barksdale fell amid a hail of gunfire. When his men finally left the field, they had to leave their commander behind; he fell into enemy hands.

Two Union soldiers – Private David Parker of the 14th Vermont and Musician Robert Cassidy of the 148th Pennsylvania – wrote letters to the Narcissa Barksdale after the war to tell her about her husband’s death. (Most unusual.) Parker had found the general west of Plum Run near midnight on July 2, 1863, and helped carry him to a Second Corps aid station on the Taneytown Road behind Cemetery Ridge.

Cassidy was helping Assistant Surgeon Alfred Hamilton of the 148th Pennsylvania who ran that aid station at the small, two-story home of Gettysburg shoemaker and widower Jacob Hummelbaugh, just to the rear of the Union lines on Taneytown Road. The house was already full of wounded and dying, so someone made a bed of blankets for the dying general in the dooryard.

Cassidy gave Barksdale water with a spoon because he was too injured to sit up. According to Cassidy the man said: “Beware! You will have Longstreet thundering in your rear in the morning.” When the general identified himself, Cassidy called Assistant Surgeon Hamilton out to see their famous prisoner.

In the book, The Story of Our Regiment, A History of the 148th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Written by the Comrades (1904), Hamilton wrote that he found wounds in Barksdale’s left chest, through his jacket which was trimmed with gold braid, and in his left leg. Barksdale had been hit at least three times and probably had a punctured lung. Blood was spraying from the chest wound with every breath he took. All that could be done was to give him morphine for pain.

General Barksdake died alone during the night. After dawn, Cassidy saw that souvenir hunters had taken some of his gold braid and the Mississippi star buttons from his jacket. The studs with Masonic emblems had been removed from his linen shirt. Cassidy took the last remaining accoutrements from his uniform which he later gave to his wife. Barksdale was buried in a temporary grave behind the Hummelbaugh House.

Narcissa Barksdale came to Gettysburg after the war with her husband’s favorite hunting dog to retrieve his remains to be buried at home in Mississippi. As they unearthed the burial site, the dog whimpered, and soon began to wail. Barksdale’s dog refused to leave his master’s grave, even after his corpse was removed. Mrs. Barksdale had no choice but to leave the animal behind. Every night, the poor animal howled and whimpered. Finally, there was silence.

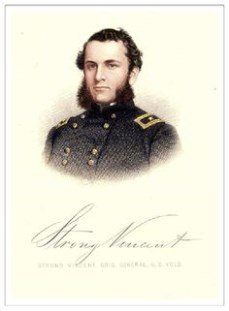

Elizabeth Vincent

Strong Vincent, a young lawyer in Erie, Pennsylvania, enlisted in the Union Army April 16, 1861, the day after President Abraham Lincoln first called for volunteers. He married his fiancee Elizabeth Carter in Jersey City, New Jersey April 25, 1861. Elizabeth was described as a very handsome, tall and graceful woman. She was a skilled horsewoman, and she gave him her riding crop to take with him when he left for the war the day after their wedding.

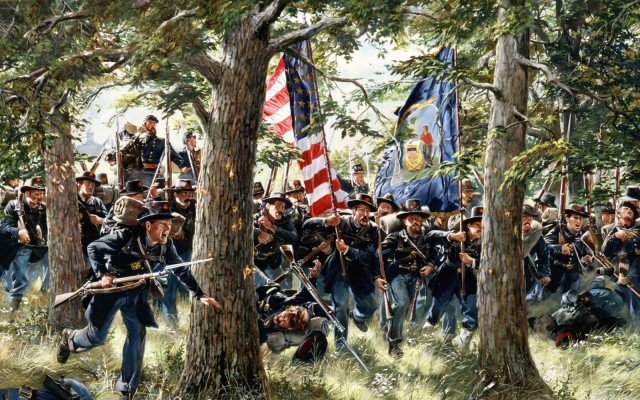

Images: Strong and Elizabeth Vincent

Elizabeth was pregnant with their first child when Strong Vincent began the Gettysburg Campaign. He passed his 26th birthday on the march to Gettysburg. His letters to Elizabeth were filled with phrases about the righteousness of the Union cause:

Surely the right will prevail. If I live we will rejoice in our country’s success. If I fall, remember you have given your husband to the most righteous cause that ever widowed a woman.

Colonel Strong Vincent and his brigade arrived at the Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863 and were soon swept up in the fray. General Daniel Sickles had disobeyed orders by moving his corps forward, leaving Little Round Top undefended. Chief Engineer of the Army of the Potomac General Gouverneur Warren recognized the importance of the hill and began looking for Union troops to occupy it before the oncoming Confederates could.

Vincent rushed his brigade to the rocky hill on the double quick. Urging his troops to repel the Rebels, Vincent mounted a large boulder and brandished the riding crop Elizabeth had given to him, shouting to his men “Don’t give an inch!” A bullet struck him through the thigh and groin and he fell. Vincent was carried to the George Spangler Farm, where he lay dying for five days, unable to be transported home due to the severity of his injury.

His corps commander, General George Sykes, described Vincent’s actions in his official report of the battle:

Night closed the fight. The key of the battle-field was in our possession intact. Vincent, [Stephen] Weed, and Charles Hazlett, chiefs lamented throughout the corps and army, sealed with their lives the spot intrusted to their keeping, and on which so much depended…. General Weed and Colonel Vincent, officers of rare promise, gave their lives to their country.

In the early morning hours of July 3, Union General George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, sent a telegram to General Henry Halleck at the War Department, stating:

I would respectfully request that Col. Strong Vincent, Eighty-Third Pennsylvania Regiment, be made a Brigadier-General of Volunteers for gallant conduct on the field yesterday. He is mortally wounded, and it would gratify his friends, as well as myself. It was my intention to have recommended him with others, should he live.

President Lincoln acted immediately and promoted Vincent to brigadier general later that day. According to Private Oliver Willcox Norton in Army Letters 1861-1865: “His commission as Brigadier General was read to him on his deathbed.”

Elizabeth Vincent gave birth to a girl she named Blanche two months later, but the baby died before reaching the age of one.

The portion of Little Round Top to the southeast of Sykes Avenue on the battlefield is known as Vincent’s Spur. Vincent is portrayed in the film Gettysburg by Maxwell Caulfield.

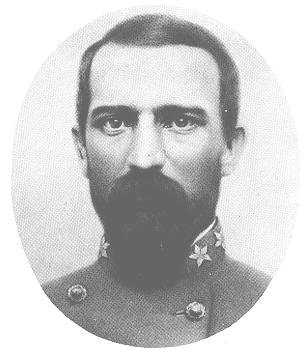

Mary Frances Shepperd Pender

William Dorsey Pender, called Dorsey, graduated from West Point, finishing 19th in a class of 46 in 1854. This distinguished class included these future Civil War generals: John Pegram, G.W. Custis Lee, J.E.B. Stuart, Stephen D. Lee, and Oliver O. Howard.

In 1859, Pender and Mary Frances Shepperd were married. The daughter of longtime Congressman Augustine Henry Shepperd, she was lovingly called Fanny by those dear to her. Two sons, Turner and Dorsey, followed in the next two years. Fanny loved Dorsey so much that she travelled with him as he was sent from post to post on the frontier that was then West Coast.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Pender offered his services to the Confederacy. He was promoted to Brigadier General a week later. During the early months of 1863, many Confederate congressmen and fellow generals petitioned General Lee to promote Pender to division command.

After the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, Lee promoted Pender to major general and put him at the head of General A.P. Hill‘s old Light Division, one of the best divisions in the army. At twenty-nine Pender was the youngest and the fastest-rising officer in the Army of Northern Virginia.

During the first day at Gettysburg, Pender helped push the Federal Army back through town to the heights beyond. Late on the second day, July 2, 1863, General Hill, sent Pender’s Division forward to attack the Union lines. General Pender was riding down his line when he was struck in the thigh by a two-inch piece of an exploding artillery shell.

Image: General Dorsey Pender

Mortally wounded at Gettysburg

Pender was quickly taken to the rear. The wound bled profusely, but the surgeons controlled the hemorrhaging. The next morning, he attempted to mount his horse, but it was too painful. His participation in the battle was over. The general was placed in an ambulance and carried back to Virginia with the retreating army.

On July 18, in Staunton, Virginia, an artery in his leg ruptured. Surgeons attempted to mend the artery but it was impossible. They then performed an emergency amputation of the leg in an attempt to save him, but Pender died a few hours later, leaving this message for his family:

Tell my wife that I do not fear to die. I can confidently resign my soul to God, trusting in the atonement of Jesus Christ. My only regret is to leave her and our two children. I have always tried to do my duty in every sphere in which Providence has placed me.

Upon receiving word of her husband’s passing, Fanny Pender locked herself in her bedroom, and her hair soon turned white. A few months later she gave birth to their third son Stephen Lee Pender, who was named for her husband’s friend and classmate.

Fanny Pender never remarried. After the war, she supported herself and her family by operating a boarding school until 1885, when she was appointed postmistress of Tarboro, North Carolina. In 1875, she witnessed the naming of Pender County, North Carolina, in honor of the man she had loved so much. She died of acute colitis on July 3, 1922, at the age of 82.

Robert E. Lee described Pender in these words:

The confidence and admiration inspired by his courage and capacity as an officer were only equaled by the esteem and respect entertained by all with whom he was associated… Wounded on several occasions, he never left his command in action until he received the injury that resulted in his death.

In 1929, at the dedication of the North Carolina Memorial at the Gettysburg battlefield, former Governor Angus McLean stated:

A great poet has said that “battles are fought by the mothers of men;” and that “back of every brave soldier is a brave woman.” Peculiarly was this true of the old South. Our soldiers who fought here had back of them a great gallery of Spartan womanhood.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Strong Vincent

Wikipedia: William Dorsey Pender

GoErie.com: Strong Vincent at Gettysburg

13th Mississippi Infantry Regiment: Barksdale’s Death

And Speaking of Which: The Grandest Charge Ever Made