Women Who Served as Nurses for the Union Army

Washington, DC

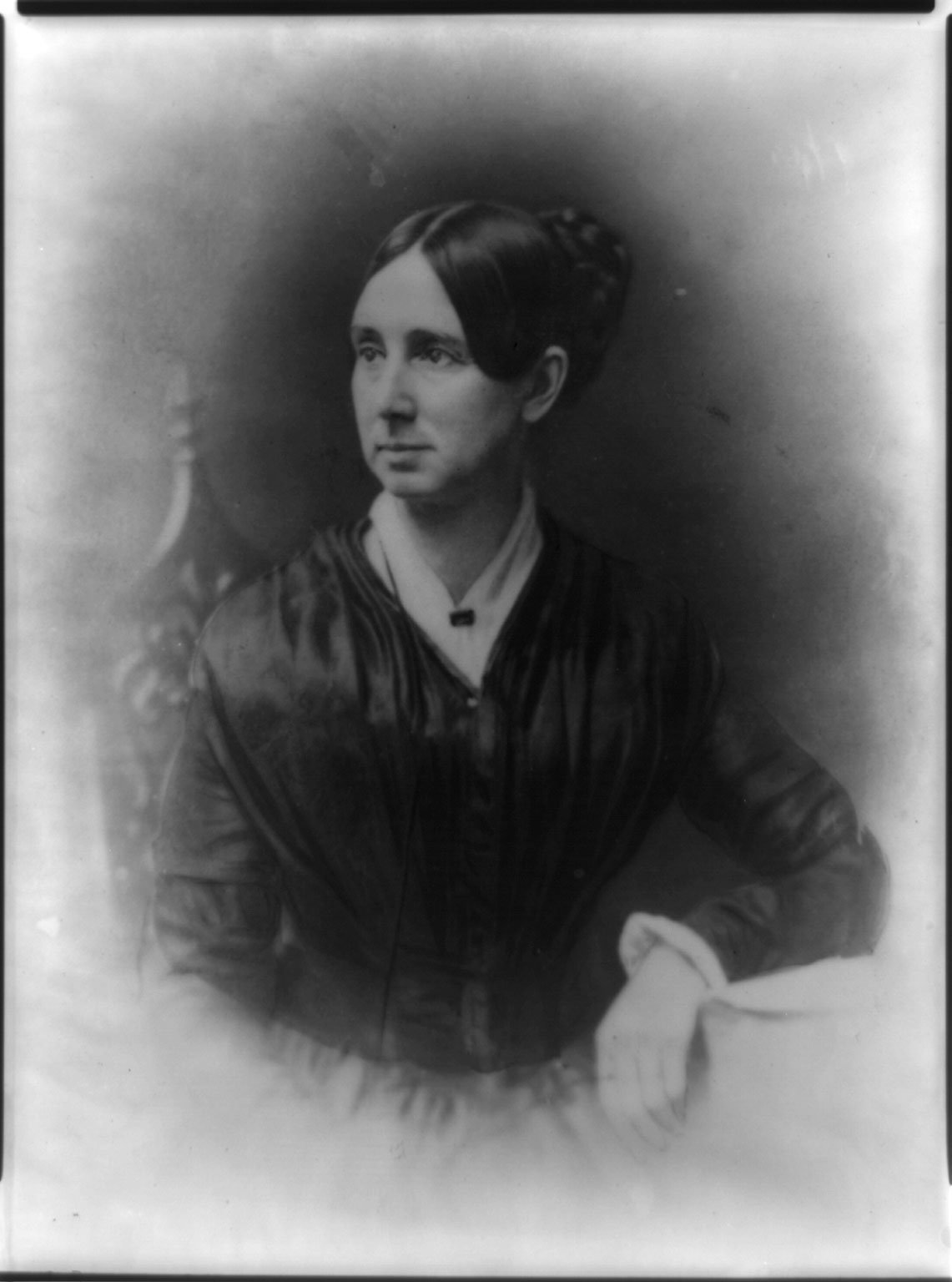

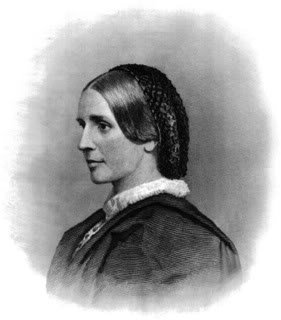

Soon after the Civil War began, the United States government established the Army Nursing Service and appointed Dorothea Dix as its Superintendent of Women Nurses. The 60-year-old Dix quickly established stringent qualifications for her volunteer nurses.

Image: Civil War Nurses Memorial

Washington, DC

Each nursing candidate had to be “past 30 years of age, healthy, plain almost to repulsion in dress and devoid of personal attractions.” They had to be able “to cook all kinds of low diet” and avoid “colored dresses, hoops, curls, jewelry and flowers on their bonnets.” They could not associate with either surgeons or patients socially, and they must always insist upon their rights as the senior attendants in the wards. Still, many women answered the call.

To insure that her volunteers met these criteria, Dix conducted intensely personal interviews with the applicants. Although her friends described Dorothea Dix as a sensitive and selfless person, her nurses feared her. Behind her back, they called her “Dragon Dix” because of her strict rules concerning the appearance and behavior of the Union army nurses.

In June 1861, the United States Sanitary Commission was established. This organization monitored camps in the field, the quality of hospital food, and the availability of clothing and medical supplies. Its purpose was to investigate and advise the officials in matters of sanitation and hygiene. By war’s end, the commission had distributed almost $15 million worth of supplies, wholly provided by the citizens of the United States.

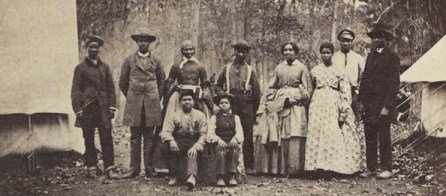

Many volunteer nurses were unprepared for the emotional impact of seeing the war up close – bodies that were mangled by bullets and bayonets, the anguished cries of the wounded, and the stench of rotting amputated limbs. Some of these women had husbands or sons at the front; others were motivated by patriotism alone.

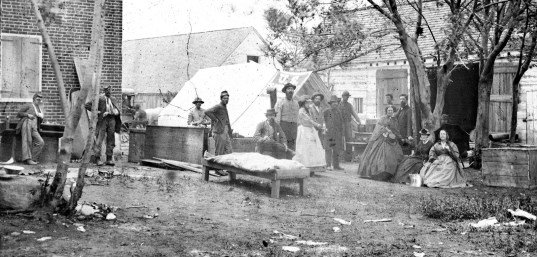

The nurses cleaned wounds, performed minor surgeries, administered treatments, and had to endure hard physical labor. They worked under horrible conditions, were grossly understaffed, and constantly exhausted. They were also expected to serve as a mother figure to the soldiers and to always be feminine and cheerful to the patients.

In general hospitals, nurses supervised the preparation and serving of the daily meals and oversaw the distribution of clothing and supplies from the Christian Commission and the Sanitary Commission. Most importantly, nurses were to provide all physical, emotional, and spiritual care for the patients and their families.

In September 1863, the War Department approved a new policy concerning nursing volunteers. Individual surgeons were allowed to appoint their own nurses, provided they had the recommendation of the Surgeon General. This offered the nurses who had been rejected by Dorothea Dix another way to join the nursing corps, and younger nurses began to appear in the hospitals.

Female nurses usually worked in base hospitals, far away from the front lines. But some, like Clara Barton, served in field hospitals. Barton sometimes reached the battlefield before the fighting had ended. At Antietam, Maryland, she treated the wounded on the field by removing bullets with her pocketknife. When she ran out of bandages, she wrapped their wounds in cornhusks.

By 1863, both armies had built larger and better field hospitals. Regimental hospitals were clustered together, with some differences in the duties of the various medical officers. The chief surgeon of the brigade was in charge. Then, brigade hospitals clustered into division hospitals, and by 1864 corps hospitals were established. There, the best surgeons operated, with one surgeon in charge of records, another in charge of drugs, and another of supplies.

The Army of the Potomac, under its medical director Jonathan Letterman, developed the Letterman Ambulance Plan, first put into service after the Battle of Antietam. In this system, the ambulance, with two stretcher-bearers and one driver per ambulance, collected the wounded from the field, brought them to the dressing stations, and later took them to the field hospital.

Nursing was emotionally draining, and it could be life-threatening. Communicable diseases took the lives of some Union nurses, contracted through direct contact with their patients. One nurse wondered what took more courage: a man stepping onto the battlefield or a nurse entering a smallpox ward.

These women left the safety of their homes and served their country in a time of great need. Working side by side with poorly trained physicians, these pioneers unselfishly provided aid to the sick and wounded. They exposed themselves to horrific sights, but at the end of the war, they received no praise.

The work of the Union nurses of the Civil war aided in the development of nursing as a profession, as well as women’s rights. Soon after the war, the American Medical Association authorized the founding of a nurses’ training academy. The Connecticut and Boston Training Schools for Nurses were opened in the 1870s.

My overwhelming desire in writing this blog is that everyone will come to realize the contributions these heroic women made to the history of our country and to the advancement of the rights of women. We owe them a debt of gratitude that is long overdue.