Civil War Nurse in Virginia

Phoebe Yates Levy was born on August 18, 1823. She was the fourth of six daughters of a prosperous and socially prominent Jewish family in Charleston, South Carolina. Her father was a successful merchant and her mother was a popular actress.

Phoebe Yates Levy was born on August 18, 1823. She was the fourth of six daughters of a prosperous and socially prominent Jewish family in Charleston, South Carolina. Her father was a successful merchant and her mother was a popular actress.

Members of Phoebe’s family were quite active in public life during the war. Her sister Eugenia Levy Phillips, a Confederate spy, was banished to an island. Her brother Samuel was the highest ranking Jewish officer in Savannah, Georgia.

The family’s wealth enabled them to gain acceptance in the community, which wasn’t easy for Jews. They moved among Charleston’s elite until a series of financial setbacks sent them to Savannah, Georgia, in 1850.

Phoebe was then 27 years old and wanted a life of her own. She married Thomas Pember, a non-Jew, in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1856. Soon after the wedding, Thomas contracted tuberculosis, and the couple moved to the South, hoping his health would improve there.

On July 9, 1861, Thomas died of tuberculosis in Aiken, South Carolina. He was 36 years old. Widowed and childless, Phoebe returned to her family, who had fled to Marietta, Georgia, to escape the ravages of war.

In November 1862, Mrs. George Randolph, wife of the Confederate Secretary of War, offered Phoebe a position as a matron at the Chimborazo Hospital, a Confederate military hospital outside of Richmond, Virginia. Though Phoebe had no professional medical training, she believed that caring for her husband through years of illness qualified her for hospital work.

Chimborazo was said to be the largest military hospital in the world at that time. A complex of long, one-story whitewashed buildings sprawled atop a hill, the hospital began receiving patients in 1862 and was eventually expanded to 150 wards.

Each ward was a separate building, thirty feet wide and one hundred feet long, and housed approximately forty to sixty patients. Phoebe supervised 150 wards, and an estimated 15,000 soldiers were under her care during the Civil War.

On December 1, 1862, 39-year-old Phoebe Yates Pember became the chief matron of the Second Division at Chimborazo, which was one of five divisions in the hospital. Though she was confident in her abilities, she encountered much opposition, but she was not one to be pushed around.

In response to criticism that ladies should not see the horrors of a hospital, Phoebe replied:

In the midst of suffering and death, hoping with those almost beyond hope in this world; praying by the bedside of the lonely and heart stricken; closing the eyes of the boys hardly old enough to realize man’s sorrows, much less suffer man’s fierce hate, a woman must soar beyond the conventional modesty considered correct under different circumstances.

Though plagued by shortages of medicine and supplies, and having to contend with doctors who didn’t approve of female nurses, Phoebe cared for sick and wounded Confederate soldiers for the balance of the war.

But her position seemed little more than that of a cook, until the surgeon-in-charge, Dr. James McCaw, found her peeling potatoes one day. McCaw made a thorough study of hospital rules and organized a full staff under Phoebe’s jurisdiction. She was provided with an assistant matron, cooks and bakers, and two laborers to perform menial tasks.

She also made sure that the orders of surgeons were performed properly, and that the medical and dietary needs of her patients were fulfilled. She wrote letters for the soldiers and comforted the dying, and set a pattern of compassionate care for the terminally ill that served as a model for future generations of nurses.

She eventually found some respite from her duties by renting a room in town, to which she returned at night. Meanwhile, her patients taught her something about courage:

No words can do justice to the uncomplaining nature of the Southern soldier. Day after day, whether lying wasted by disease or burning up with fever, torn with wounds or sinking from debility, a groan was seldom heard.

As the war progressed, casualties multiplied and Phoebe’s duties increased. Large numbers of incoming wounded caused shortages of medical supplies, surgeons and assistants, and hospital beds. She arranged for makeshift beds and continually washed and dressed minor wounds, preparing the more difficult cases for the surgeons.

Phoebe wrote in her memoir about Richmond:

The horrors that attended, in other and past times, the bombardment of a city, were experienced to a great degree in Richmond during the fighting around us. The close proximity to the scenes of strife; the din of battle, the bursting of shells, the fresh wounds of the men hourly brought in, were daily occurrences.

Walking home after the duties of the Hospital were over, often when evening had well set in, during this time, the pavement around the railroad depot would be lined with wounded men, laid there to wait for ambulances to take them to the receiving hospital; some on stretchers, others on the bare bricks, or a thin blanket, suffering from wounds hastily wrapped around with the coarse, galling, unbleached homespun bandages, in which the blood had stiffened till every crease cut like a knife.

Women, passing like myself, would put down their basket or bundle, and ringing at the bell of any neighboring house, ask for basin and soap, and a few soft rags, and going from one sufferer to another, alleviate, with what skill they had the pain of wounds, change the uneasy position and allay the thirst. Many passing, would stop and look on, till the labor appearing to require no particular skill, they too would follow the example set them, and asking occasionally a word of advice, do their part carefully and willingly.

Idle boys passing, would get a pine knot, or tallow candle, and stand quietly as torch bearers, till the scene, with its gathering accessories, formed a strange picture, not easily forgotten. Persons passing in vehicles would sometimes alight, and, choosing the patients most in want of surgical aid, put them in and send them to the Seabrook Hospital, continuing their way on foot. There was very little conversation carried on, no necessity for introductions, and no names ever asked.

Phoebe remained at Chimborazo until the Confederate surrender in April, 1865. She stayed with her patients after the fall of Richmond and until the facility was taken over by Federal authorities. During that time, she cared for both Confederate and Union soldiers. A total of 76,000 patients had been cared for at Chimborazo by the end of the Civil War.

She suddenly found herself alone in Union-occupied Richmond, without prospects, and with just a silver 10-cent piece and a box of useless Confederate money to her name. Laughing at her lot, she spent her paltry remaining funds on “a box of matches and five cocoa-nut cakes.”

When her responsibilities in Richmond were completed, Phoebe returned to Savannah, Georgia. There, she maintained her elite social status, and traveled extensively in the United States and Europe. She was honored by Confederate veterans’ organizations during her later years.

Phoebe also wrote her memoirs, A Southern Woman’s Story: Life in Confederate Richmond. First published in 1879, it is rated by Civil War historian Douglas Southall Freeman as “the most realistic treatment of the war” ever published.

Phoebe Yates Pember died on March 4, 1913, at the age of 89, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She was buried in Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah. An obelisk was later erected there in her memory.

In 1995, her portrait appeared on a sheet of 20 stamps issued by the United States Postal Service, which commemorated important persons and events during the Civil War.

SOURCES

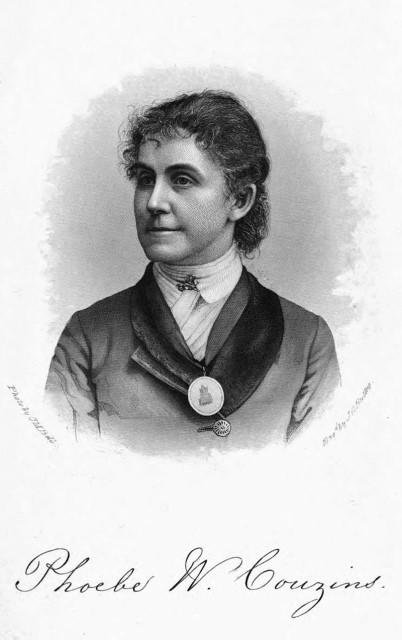

Phoebe Yates Levy Pember