Wife of Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles

Mary Jane Hale was born June 18, 1817, in Glastonbury, Connecticut, the daughter of Elias White Hale and Jane Mullhallan Hale. Her father graduated from Yale College in 1794, and practiced law in Mifflin and Centre Counties, Pennsylvania.

Mary Jane Hale was born June 18, 1817, in Glastonbury, Connecticut, the daughter of Elias White Hale and Jane Mullhallan Hale. Her father graduated from Yale College in 1794, and practiced law in Mifflin and Centre Counties, Pennsylvania.

Gideon Welles was born July 1, 1802, in Glastonbury, Connecticut. He was a member of the seventh generation of his family in America. His original immigrant ancestor, Thomas Welles, arrived in 1635 and was the only man in Connecticut’s history to hold all four top government offices: governor, deputy governor, treasurer, and secretary.

Welles earned a degree at the American Literary, Scientific, and Military Academy at Norwich, Vermont. He studied law, but soon shifted to journalism and became the founder and editor of the Hartford Times in 1826. From 1827–1835, he was a member of the Connecticut House of Representatives.

Gideon Welles married Mary Jane Hale on June 16, 1835, at Lewiston, Pennsylvania.

Their children were:

Anna Jane Welles (1836 – 1852)

Samuel Welles (1838 – 1853)

Edward Gideon Welles (1840 – 1843)

Thomas Gideon Welles (1846 – 1892)

John Arthur Welles (1849 – 1883)

Herbert Welles (1852 – 1853)

Hubert Welles (1853 – 1862)

Mary Juanita Welles (1854 – 1858)

Gideon Welles became an early supporter of Andrew Jackson, and was a personal adviser to Jackson while he was president (1829–1837).

Welles served in various governmental posts, including State Controller of Public Accounts in 1835, Postmaster of Hartford (1836–41), and Chief of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing for the Navy (1846–49). During his three years in the Navy Department, he acquired valuable administrative experience and made enduring friendships.

By the 1850s, Welles had come to oppose slavery, the Fugitive Slave Law, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Although he failed in his first tries at national office, Welles built a reputation among a wide circle of influential Americans through his writings and travels, and devoted his energies and considerable talents as a journalist to the fight against slavery.

Mainly because of his strong antislavery views, Welles left the Democratic Party and helped organize the new Republican Party in Connecticut in 1856. That same year Welles was defeated in a bid for the governorship; but he became a Republican national committeeman.

He also founded a newspaper, the Hartford Evening Press, in 1856 that would espouse Republican ideals for decades thereafter.

Union Secretary of the Navy

Welles’ strong support of Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election made him the logical candidate from New England for Lincoln’s cabinet, and on March 7 1861, the new president named Welles his Secretary of the Navy. With no prior experience, Welles proved quite adept at the job, though he found the Naval Department in disarray, with Southern officers resigning en masse.

Through Congress, Welles revitalized a Navy Department with its ships scattered at various stations throughout the world, two of its most important navy yards seized by the Confederacy, and many of its former employees now serving in the Confederate Navy. In July 1861, he established the post of assistant secretary and temporary volunteer officers to fill wartime needs, and retired older officers.

In July 1861, Welles allowed Union ships to keep contrabands – escaped slaves – on board. By September, he authorized enlisting them under the same regulations as other enlistments. And in July 1862, he ordered the East Gulf Blockading Squadron actively to recruit contrabands.

When William H. Seward argued for a Union blockade of Southern ports, Welles strongly argued against the action but was eventually convinced by Lincoln. Despite his misgivings, Welles’ efforts to implement the blockade and promote the construction of ironclad ships proved extraordinarily effective. From 76 ships and 7600 sailors in 1861, by 1865 the Navy had expanded almost tenfold.

He resisted public demands of ships for the Northern coastline while concentrating on blockading and strangling the Confederacy. While never completely effective in sealing off all 3500 miles of Southern coastline – there were numerous inlets through which small Confederate craft could slip through the Federal blockade – it greatly contributed to the Union victory.

Welles’ implementation of the blockade weakened the Confederacy’s ability to finance the war by limiting the cotton trade, and he constantly strengthened it until the South was almost completely sealed off from the rest of the world. He used monitors for Southern harbors and ironclad riverboats on the Mississippi River. He also supported development of armored cruisers, heavy ordnance, and steam machinery.

Shrewd, methodical, and knowledgeable and a man of unusual energy, the Union’s Secretary of the Navy rapidly doubled the size of the Navy and took an active part in the direction of the naval war against the South. His ideas influenced the designs of ordnance, machinery and improvements in the navy yards – both existing and planned.

Quick to reprimand persons he believed negligent or competent, Welles angered some high-ranking officers, and offended politicians who wanted navy installations in their districts. He took a direct part in shaping naval strategy and tactics, and is given deserved credit for the general success of the Federal Navy.

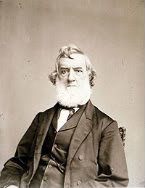

Image: Gideon Welles

This photograph of Welles by Mathew Brady’s studio was taken in 1865, when Brady was taking photographs of the notables who had been present at Lincoln’s bedside just before he died. Welles had been one of the many. The photographs were then used to compose a picture entitled The Last Hours of Lincoln, painted by Alonzo Chappel. This head-on view was taken at the same time and is perhaps the best view extant of Welles’ ill-fitting wig, which received ample notice in his day.

In Abraham Lincoln’s Cabinet

Despite his successes, Gideon Welles was never at ease in the Cabinet. His conservative views led to arguments with some of his fellow officers, particularly William H. Seward (Secretary of State) and Edwin M. Stanton (Secretary of War).

On July 7, 1863, Welles received a telegram that Vicksburg had fallen to Ulysses S. Grant and brought the news to President Lincoln in his office, as Welles wrote in his diary:

The President was detailing certain points relative to Grant’s movements on the map to Chase and two or three others, when I gave him the tidings. Putting down the map, he rose at once, said we would drop these topics, and ‘I myself will telegraph this news to General Meade.’

He seized his hat, but suddenly stopped, his countenance beaming with joy; he caught my hand, and, throwing his arm around me, exclaimed: ‘What can we do for the Secretary of the Navy for this glorious intelligence? He is always giving us good news. I cannot, in words, tell you my joy over this result. It is great, Mr. Welles, it is great!’ We talked across the lawn together. ‘This,’ said he, ‘will relieve Banks. It will inspire me.’

The Secretary of the Navy was critical of cabinet meetings about which he repeatedly complained in his diary because of their irregularity and informality. He generally disapproved of how most other cabinet members behaved, in their departments and in cabinet meetings.

In Andrew Johnson’s Cabinet

Following Lincoln’s death by assassination in April 1865, Welles was retained as Secretary of the Navy by Andrew Johnson. The same moderation that led him to support Lincoln’s announced plans for Reconstruction led him to support President Johnson in opposition to many of his former Republican colleagues. Welles stayed through Johnson’s administration, working for the modernization of the Navy.

Even after the new President ran into difficulties, Welles loyally and enthusiastically supported Johnson throughout the impeachment proceedings. At the end of Johnson’s administration, Welles returned to private life; and, although he never again occupied public office, he remained politically active and wrote prolifically until his death.

Later Years

After leaving politics, Welles returned to Connecticut and to writing, editing his journals and authoring several books, including Lincoln and Seward, a biography published in 1874.

After retirement, he continued to speak out on public issues, and wrote many articles. His most lasting contribution is the three-volume Diary of Gideon Welles, documenting his Cabinet service from 1861–1869. The diary is an opinionated, brilliant insider’s account and analysis of events and personalities of the war years. He recognized Lincoln as “in every way large – brain included.”

At the end of 1877, his health began to wane, and an illness caused by a streptococcal infection of the throat struck him in February 1878.

Gideon Welles died February 11, 1878, in Hartford, Connecticut, at the age of seventy-five, and was buried in Cedar Hill Cemetery there.

Mary Jane Hale Welles died February 28, 1886, in Hartford, and was buried next to her husband in Cedar Hill Cemetery.

SOURCES

Gideon Welles

Wikipedia: Gideon Welles

Mr. Lincoln’s White House

Naval History and Heritage

Gideon Welles: Secretary of the Navy