Wife of General John C. Breckinridge

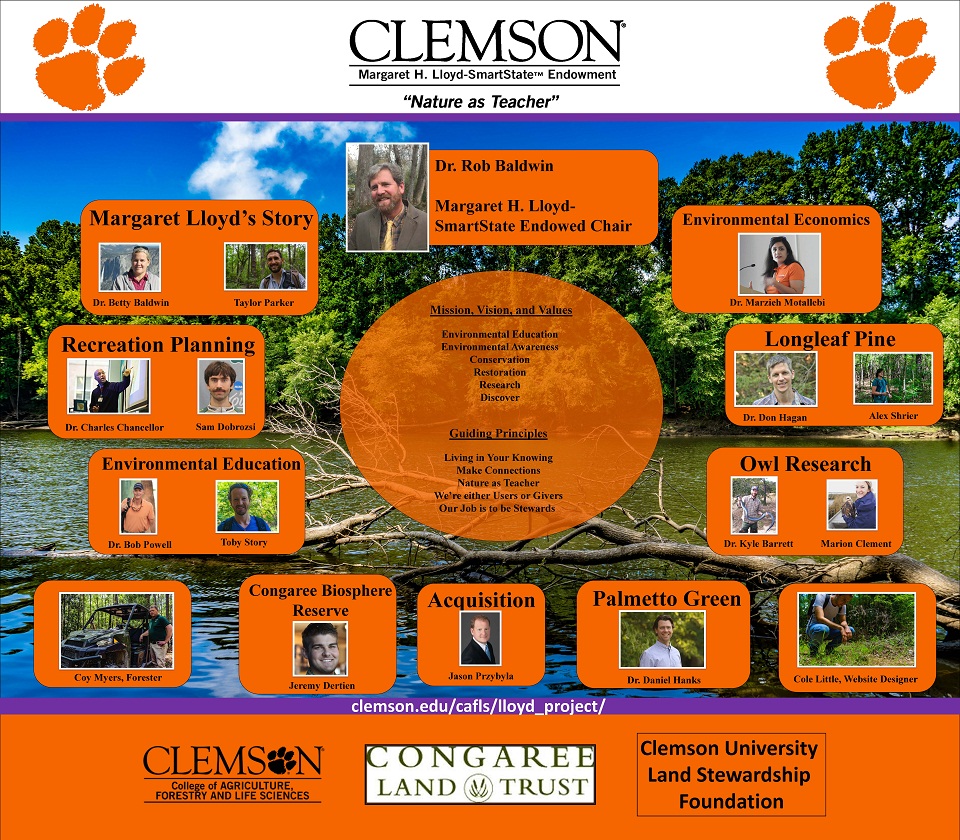

Mary Cyrene Burch was born in 1826, the daughter of Clifton Rhodes Burch and Alethia Viley Burch. Born at Cabell’s Dale, the family estate near Lexington, Kentucky, on January 16, 1821, John Cabell Breckinridge was named for his father and grandfather. His grandfather, the first John Breckinridge was a U.S. senator and served as attorney general for President Thomas Jefferson. His father, Joseph Cabell Breckinridge, a rising young politician, died at the state capital at the age of thirty-five.

Mary Cyrene Burch was born in 1826, the daughter of Clifton Rhodes Burch and Alethia Viley Burch. Born at Cabell’s Dale, the family estate near Lexington, Kentucky, on January 16, 1821, John Cabell Breckinridge was named for his father and grandfather. His grandfather, the first John Breckinridge was a U.S. senator and served as attorney general for President Thomas Jefferson. His father, Joseph Cabell Breckinridge, a rising young politician, died at the state capital at the age of thirty-five.

Image: Husband of Mary Breckinridge

Vice President John Cabell Breckinridge

Left without resources, John’s mother, Mary Clay Smith Breckinridge, took her children back to Cabell’s Dale to live with their paternal grandmother, known affectionately as “Grandma Black Cap.” John and his sisters were raised by their mother and grandmother, who often regaled the children with stories of their grandfather, who had helped secure the Louisiana Purchase.

The sense of family mission that his grandmother imparted shaped young John C. Breckinridge’s self-image and directed him towards a life in public office. The family also believed strongly in education, since Breckinridge’s maternal grandfather, Samuel Stanhope Smith, had served as president of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, and his uncle Robert J. Breckinridge started Kentucky’s public school system.

Young John attended the Presbyterian Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, where he received his bachelor’s degree at seventeen. He then attended Princeton University in New Jersey before returning to Lexington to study law at Transylvania University and under Judge William Owsley. He was admitted to the bar in 1840.

A tall, strikingly handsome young man with a genial air and a powerful voice, considered by many “a perfect gentleman,” Breckinridge set out to make his fortune on the frontier. In 1841, he and his law partner Thomas W. Bullock settled in the Mississippi River town of Burlington in the Iowa Territory, but Iowa’s fierce winter gave him influenza and made him homesick for Kentucky.

When he returned home on a visit in 1843, he met and married Mary Cyrene Burch of Georgetown, Kentucky, on December 12, 1843. She was the cousin of his law partner, Thomas Bullock. The newlyweds settled in Georgetown, and had five children. John opened a law office in Lexington.

Breckinridge was known for his striking good looks, commanding personality, and oratory skills. He first gained statewide attention when he gave an address at a funeral service honoring Kentucky soldiers who were killed at the Battle of Buena Vista in the Mexican-American War.

Shortly afterwards, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and served as an officer in a Kentucky infantry regiment in Mexico. Major Breckinridge won the support of his troops for his acts of kindness, being known to give up his horse to sick and footsore soldiers. After six months in Mexico City, he returned to Kentucky to an almost inevitable political career.

Political Career

Breckinridge began to attract notice as a potential candidate for office while still in his twenties. He was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1849 as a Democrat, at the age of 28. In that election, as in all his campaigns, he demonstrated both an exceptional ability as a stump speaker and a politician’s memory for names and faces.

John’s uncle, Robert Breckinridge, was a prominent antislavery man, and as a state legislator, John supported the Kentucky Colonization Society, which was dedicated to gradual emancipation and the resettlement of free blacks outside the United States. While Breckinridge was no planter, he owned a few household slaves and idealized the southern way of life.

Shortly after the 1849 election, he met Abraham Lincoln, the Illinois legislator who had married John’s cousin Mary Todd. While visiting his wife’s family in Lexington, Lincoln paid courtesy calls on the city’s lawyers, and Lincoln and Breckinridge became friends, despite their differences in party and ideology.

Breckinridge was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives (1851 – 1855), and, obviously for political reasons, abandoned his earlier support of the gradual emancipation of slaves. He became a spokesman for the proslavery Democrats, arguing that the federal government had no right to interfere with slavery anywhere, either in the District of Columbia or in any of the territories.

The Pennsylvania newspaper publisher and political adventurer, John W. Forney, insisted that when Breckinridge came to Congress “he was in no sense an extremist.” Forney recalled how the young Breckinridge spoke with great respect about Texas Senator Sam Houston, who denounced the dangers and evils of slavery. But Forney thought that Breckinridge “was too interesting a character to be neglected by the able ultras of the South. They saw in his winning manners, attractive appearance, and rare talent for public affairs, exactly the elements they needed in their concealed designs against the country.”

Congressman Breckinridge became an ally of Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas. When Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which repealed the Missouri Compromise and left the issue of slavery in the territories to the settlers themselves, Breckinridge worked hard to enact the legislation. His support of that bill further aligned him with militant States Rights supporters.

Breckinridge hoped the Kansas-Nebraska Act would take slavery in the territories out of national politics, but the act had entirely the opposite effect. Public outrage throughout the North caused the Whig party to collapse and new antislavery parties, the Republican and the American (Know-Nothing) parties, to rise in its wake.

When the spread of Know-Nothing lodges in his district jeopardized his chances of re-election in 1855, Breckinridge declined to run for a third term. He also rejected President Pierce’s nomination to serve as minister to Spain and negotiate American annexation of Cuba, despite the Senate’s confirmation of his appointment. Citing his wife’s poor health and his own precarious finances, Breckinridge returned to Kentucky. Land speculation in the West helped him accumulate a considerable amount of money during his absence from politics.

As the Democratic convention approached in 1856, the three leading contenders – President Franklin Pierce, Senator Stephen Douglas, and former Minister to Great Britain James Buchanan – all courted Breckinridge. He attended the convention as a delegate, voting first for Pierce and then switching to Douglas. When Douglas withdrew as a gesture toward party unity, the nomination went to Buchanan. The Kentucky delegation nominated former House Speaker Linn Boyd for vice president.

When Boyd ran poorly on the first ballot, the convention switched to Breckinridge and nominated him on the second ballot, and Breckinridge was chosen by the Democrats as James Buchanan’s running mate in the 1856 presidential campaign.

Although Tennessee’s Governor Andrew Johnson grumbled that Breckinridge’s lack of national reputation would hurt the ticket, Buchanan’s managers were pleased with the choice. They thought Breckinridge would appease Douglas, since the two men had been closely identified through their work on the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Being present at the convention, Breckinridge was prevailed upon to make a short acceptance speech, thanking the delegates for the nomination, endorsing Buchanan and the platform, and reaffirming his position as a “state’s rights man.”

The election was a three-way race among the Democrats under Buchanan, the Republicans under John Charles Frémont, and the Know-Nothings under former President Millard Fillmore. Denouncing the antislavery policies of the Republicans and Know-Nothings, Breckinridge described himself not as proslavery, but as a defender of the people’s constitutional right to make their own territorial laws, a position that caused some Deep South extremists to accuse him of harboring abolitionist views.

Breaking with tradition, Breckinridge campaigned actively for his ticket. In November, Democrats carried all the slaveholding states except Maryland (which went Know-Nothing) and enough northern states to win the election. Breckinridge was proud that Kentucky voted for a Democratic presidential ticket for the first time since 1828. Inaugurated at age 36, Breckinridge became the youngest Vice President in American history.

Although vice presidents generally had little influence in this period of history, Breckinridge had almost no role because Buchanan excluded him from his administration. Viewing Breckinridge as part of the Pierce-Douglas faction, Buchanan almost never consulted him, and rarely invited him to the White House for either political or social gatherings. However, Vice President Breckinridge was respected for presiding over the U.S. Senate with fairness during a contentious time in American history. While he defended the right of individuals to make their own territorial laws, he also counseled against secession and appealed for national unity.

As the presidential election of 1860 approached, the country was increasingly divided over the issue of slavery. The Democratic Party split when the Southern states walked out of the convention. The Northern Democrats nominated Illinois senator Stephen Douglas.

Southern Democrats convened their own convention and nominated John Breckinridge for president on a pro-slavery platform, with Oregon senator Joseph Lane as his running mate. Breckinridge had no desire to head this doomed ticket – he had already been appointed to the U.S. Senate by the Kentucky legislature. He consented to run out of a sense of duty, and hoped that Douglas could be persuaded to withdraw in favor of a new Democratic nominee. In the end, both he and Douglas remained in the race. Attempts at combining forces were only partially successful.

The 1860 presidential election resulted in Abraham Lincoln sweeping the North, while winning only 39 percent of the popular vote. Breckinridge came in third in the popular vote, carrying 12 of the 15 slave states, but finished second in the Electoral College with a total of 72 electoral votes. He failed to carry a single free state and, to his particular disappointment, was defeated in Kentucky. The race put Breckinridge at odds with his uncle, Robert Jefferson Breckinridge, who supported Lincoln.

The Civil War

The results of the 1860 election revealed how polarized the nation had become. When Breckinridge assumed his Senate seat, he hoped that he might be able to help the nation avoid war. He worked hard to promote compromise proposals that would allay Southern fears of Republican antislavery policies. He did not support secession, but had little chance of influencing Southern states that had already started seceding from the Union.

Image: Confederate General John C. Breckinridge

Image: Confederate General John C. Breckinridge

Senator Breckinridge returned to Kentucky to try to keep his state neutral; he spoke at a number of peace rallies. Despite his efforts, pro-Union forces in the state legislature voted to remain in the Union on September 18, 1861. He could no longer find any neutral ground, no way to endorse both the Union and the southern way of life.

Unlike other Confederate leaders, such as Robert E. Lee, who followed the will of their states, Breckinridge broke with his state. Forced to choose sides, Breckinridge joined his friends in the Confederacy. When another large peace rally was scheduled for September 21, the legislature sent a regiment to break up the meeting and to arrest Breckinridge. Forewarned, he fled to Virginia.

On December 4, 1861, the Senate by a 36 to 0 vote expelled the Kentucky senator, declaring that Breckinridge, “the traitor,” had “joined the enemies of his country.” Ten Southern Senators had been expelled earlier that year. Reacting to his expulsion, he declared, “I exchange with proud satisfaction a term of six years in the Senate of the United States for the musket of a soldier.”

Although his cousin Mary Todd Lincoln resided in the White House, and his home state of Kentucky remained in the Union, the turbulence of the times led Breckinridge to become the second vice president (after Aaron Burr) to be accused of treason when he joined the Confederate Army and took up arms against the Union.

In Richmond, Breckinridge volunteered his services, and was appointed brigadier general in the Confederate Army by Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and placed in command of the First Kentucky Brigade – nicknamed the Orphan Brigade because its men felt orphaned by Kentucky’s state government, which remained loyal to the Union.

His initial hope was to return to his native state and spark a pro-Confederate uprising. When this failed to happen, he retreated to Tennessee in the spring of 1862 and served under General Albert Sidney Johnston’s forces during the Battle of Shiloh, in which he was wounded. His heroic performance there raised his rank to that of major general.

General Breckinridge developed an intense personal dislike of CSA General Braxton Bragg, the commander of the Army of Tennessee. He considered Bragg incompetent, a point of view shared by many other Confederate officers. For his part, Bragg despised Breckinridge and tried to undermine his career with accusations that he was a drunkard.

Furthermore, Breckinridge felt that Bragg was unfair in his treatment of Kentucky troops in Confederate service. At the Battle of Stones River near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, Bragg ordered Breckinridge’s division to launch a near-suicidal attack on the Union lines on January 2, 1863. Breckinridge survived the attack, but he lost nearly one-third of his Kentucky troops, primarily the Orphan Brigade. He was devastated by the disaster.

Breckinridge continued to fight with Bragg’s army, and helped achieve victory for the Confederate army at the Battle of Chickamauga on September 20, 1863, and in the unsuccessful defense of Missionary Ridge at Chattanooga on November 25, 1863. As a commander, Breckinridge proved to be resourceful and courageous, inspiring great loyalty in his troops.

In 1863, Breckinridge was brought to the Eastern Theater, and put in charge of Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley. He defeated a superior Union force led by USA General Franz Sigel at the Battle of New Market, which included the famous charge of cadets from the Virginia Military Institute.

In June 1864, General Breckinridge reinforced Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, and held the line against General Ulysses S. Grant’s assault at the Battle of Cold Harbor. In July, Breckinridge participated in CSA General Jubal Early’s Raid on Washington, DC, moving north through the Shenandoah Valley and crossing into Maryland. He fought at the Battle of Monocacy in early July, and was with Early when the Confederate force probed the defenses of Washington.

Breckinridge’s troops advanced as far as Silver Spring, Maryland, and got so close to Washington that he could see the newly completed Capitol dome, and General Early joked that he would allow him to lead the advance into the city so that he could sit in the vice-presidential chair again. But Federal troops halted the Confederates, who retreated back to the Shenandoah Valley.

There they confronted Union troops commanded by USA General Philip H. Sheridan at Winchester, Virginia. The Third Battle of Winchester, was fought on September 19, 1864. CSA General John B. Gordon later recalled that Breckinridge was “desperately reckless” during that campaign, and “literally seemed to court death.” When Gordon urged him to be careful, Breckinridge replied, “Well, general, there is little left for me if our cause is to fail.”

General Breckinridge took command of Confederate forces in southwestern Virginia in September 1864, where Confederate forces were in great disarray. He reorganized the department and led a raid into northeastern Tennessee.

Following a victory outside of Saltville, Virginia, in October 1864, Breckinridge discovered that some Confederate troops had killed scores of black Union soldiers of the 5th United States Colored Cavalry – slaves, ex-slaves, and free men – the morning after the battle. The incident shocked and angered Breckinridge. He attempted to have the commander responsible, Felix Huston Robertson, arrested and put on trial, but was unable to achieve this before the Confederacy disintegrated.

On January 28, 1865, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed Breckinridge Confederate Secretary of War. He performed well in this final government position, firing the Confederacy’s bumbling commissary general and trying to bring order out of the chaos, but these efforts came too late.

During the chaos of the fall of Richmond in early April 1865, Breckinridge saw to it that the Confederate archives, both government and military, were not destroyed but rather captured intact by the Union forces. By so doing, he ensured that a full account of the Confederate war effort would be preserved for history.

When General Robert E. Lee surrendered his army on April 9, 1865, President Davis was determined to keep on fighting, but Breckinridge opposed continuing the war as a guerilla campaign. “This has been a magnificent epic,” he said; “in God’s name let it not terminate in farce.” Fleeing Richmond, Breckinridge commanded the troops that accompanied Davis and his cabinet through the Deep South to avoid capture. Davis was apprehended.

Indicted by the Federal government for high treason, Breckinridge feared that he would be put on trial and resolved to flee the country. With Jefferson Davis a prisoner back in the States, Breckinridge was the highest ranking official of the Confederacy still at large. He led a small party of Confederates into the wilds of Florida. Commandeering a small sloop, he survived a rough voyage across the Caribbean and found asylum in Cuba.

Following his escape from capture in June 1865, Breckinridge settled initially in exile in Canada. He lived abroad for three years, and traveled to England, France, and the Middle East during this period. The Breckinridge family spent the summer of 1866 in Niagara, on Lake Ontario, where they enjoyed the visits of family, friends, and old comrades.

Subsequently, the family settled in Toronto, Canada, where Breckinridge met other Confederate exiles, including the freed Jefferson Davis, with whom he rode to Niagara one day. Across the river, they could see the red stripes of the American flag, which Breckinridge viewed nostalgically, but the more embittered Davis described it as “the gridiron we have been fried on.”

His daughter Mary later remarked that, while exile was a quiet relief for her mother, it was hard on her father, “separated from the activities of life, and unable to do anything towards making a support for his family.” He longed to return to his country, but refused to actively seek a pardon from the Federal government. He later rejoined his family in Canada and moved into a house within sight of the United States border.

Image: Breckinridge Monument

Image: Breckinridge Monument

Vicksburg National Military Park

On Christmas Day 1868, President Andrew Johnson proclaimed a universal amnesty for all former Confederates. John and Mary Breckinridge returned to the United States in February, 1869. Stopping in many cities to visit old friends, he reached Lexington, Kentucky, a month later. He had not been to Kentucky since he fled eight years before. In welcome, a band played “Home Sweet Home,” “Dixie,” and “Hail to the Chief.”

Breckinridge declared himself finished with politics: “I no more feel the political excitements that marked the scenes of my former years than if I were an extinct volcano.” He did speak out in favor of the legal rights of freedmen and denounced the Ku Klux Klan as “idiots or villains.” Most of all, he urged forgiveness and harmony between the North and South. Though he never said so publicly, he intimated to friends that the South had been wrong to leave the Union.

Refusing all requests (including one from President Grant) to seek public office, the former vice president resumed his law practice. Various business ventures occupied much of Breckinridge’s time in his final years; he became vice president of the Elizabethtown, Lexington, and Big Sandy Railroad Company.

Although he was only fifty-four, his health began to decline in 1873, in part due to a Civil War battlefield injury to his liver. Despite his weakened condition at the end, Breckinridge surprised his doctor with his clear and strong voice. “Why, Doctor,” the famous stump speaker said from his deathbed, “I can throw my voice a mile.”

Major General John Cabell Breckinridge died of complications from cirrhosis at his home on May 17, 1875, at the age of 54. He was interred in Lexington Cemetery.

His passing was mourned throughout the country. An unfortunate symbol of sectional hatred, John C. Breckinridge suffered for his political convictions, and went on to become a champion of national healing.

Mary Cyrene Burch Breckinridge died in October 1907 at the age of 81.

SOURCES

John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge

Wikipedia: John C. Breckinridge

Confederate Major General John C. Breckinridge