Wife of Confederate General John C. Pemberton

Martha Thompson was born May 17, 1827 in Norfolk, Virginia. Little is known about her life except through her husband’s activities. She likely moved with John to many posts during his career in the United States Army in the East and the West, especially in the 1850s.

Martha Thompson was born May 17, 1827 in Norfolk, Virginia. Little is known about her life except through her husband’s activities. She likely moved with John to many posts during his career in the United States Army in the East and the West, especially in the 1850s.

John Clifford Pemberton was born August 10, 1814 to Quaker parents in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. As a teenager, John decided that he wanted and college education and began preparing for the entrance exam at the University of Pennsylvania. While at UP, Pemberton decided to study engineering at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Using his family’s connection to President Andrew Jackson to secure an appointment., Pemberton was admitted to West Point May 15, 1833. He graduated in 1837, 27th out of 50 cadets and was commissioned as an officer in the Fourth Artillery, the beginning of a long career in the U.S. Army.

Pemberton served garrison duty at several posts in New York, New Jersey, and Michigan in the late 1830s and early 1840s and was promoted to first lieutenant on March 19, 1842. He and the Fourth Artillery returned to garrison duty at Fort Monroe, Virginia in 1842, and then stationed at the U.S. Army Cavalry School in Pennsylvania in 1842 and 1843, and returned to Fort Monroe from 1844 to 1845. He served in Texas and Mexico during the Mexican-American War (1845 – 1849).

John Pemberton married Martha Thompson in January 1848, and they had three children who survived to adulthood:

Martha (Pattie) Pemberton Berman (1850 – 1940)

John Clifford Pemberton, Jr. (1853 – 1934)

Francis Rawle Pemberton (1856 – 1923)

Pemberton and his artillery next served garrison duty in Florida and during hostilities against the Seminoles (1849 – 1850). He was promoted to captain on September 16. He next served in Maryland (1851 – 1852), New York (1852 – 1856), and fought again in Florida during hostilities against the Seminoles (1856 – 1857). He served on frontier duty in Kansas, Utah, New Mexico Territory, and Minnesota (1857 – 1861), and at the Washington Arsenal in Washington, DC in 1861.

Pemberton in the Civil War

John C. Pemberton had served honorably in the United States Army for twenty-four years, and when war broke out in 1861, he agonized for weeks before deciding to fight for the Confederacy and Martha’s native state of Virginia. His two brothers fought for the Union. Pemberton resigned from the Federal army on April 24, 1861, and was appointed a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate Army, then assistant adjutant-general of the forces around and in the Southern capital of Richmond, Virginia on April 29. He was promoted to colonel on May 8 and the next day was assigned to the Virginia Provisional Army Artillery.

Pemberton was adept at military politics, and he moved rapidly up the ranks despite a lack of accomplishments. In June 1861, he was made a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. His first brigade command was in the Department of Norfolk, leading its 10th Brigade from June to November 1861.

Officials in the Union Army promoted the brigadier to major general on January 14, 1862 and assigned him to the command of the Department of South Carolina and Georgia, with his headquarters in Charleston. Pemberton’s manner was often abrasive, and his public statement that he would abandon the area rather than risk the loss of his outnumbered army and his Northern birth, caused the governors of both states in his Department to petition Confederate President Jefferson Davis for his removal. But he remained there from March 14 to August 29, 1862, strengthening Union coastal defenses in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

Pemberton at Vicksburg

Davis needed a commander for a new department in Mississippi, so he promoted Pemberton to lieutenant general in October 1862, and assigned him arguably the most difficult command in the Confederacy: the defense of Vicksburg, Mississippi, known as the Department of Mississippi and West Louisiana. The city stood on high bluffs above the Mississippi River and was well-fortified by the Confederates. This position would prove to be beyond his capabilities.

Pemberton arrived at his new headquarters in Jackson, Mississippi, on October 14, 1862. His force consisted of fewer than 50,000 men under the command of Generals Earl Van Dorn and Sterling Price. Approximately 24,000 manned the permanent garrisons at Vicksburg and Port Hudson, Louisiana. Pemberton faced his former Mexican War colleague, the aggressive Union commander General Ulysses S. Grant and over 100,000 Union soldiers.

With orders to hold the city at all costs, Pemberton revamped Vicksburg’s defenses and improved defenses along the Mississippi River. He then went to work solving supply problems and improving the morale of the troops. For several months he enjoyed remarkable success; during the winter of 1862-1863 he quashed attempts by General Grant to take Vicksburg.

In spring 1863, however, General Grant confused Pemberton with a series of diversions and crossed the Mississippi River below Vicksburg practically unnoticed. About that same time, Pemberton’s immediate superior, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston assigned Pemberton’s cavalry to the Army of Tennessee, leaving him no mounted force to scout the movement of Grant’s infantry.

In May 1863, General Grant’s campaign to take Vicksburg began in earnest, and he swept inland scoring a series of quick victories Port Gibson (May 1), Raymond (May 12), and Jackson (May 14). In an attempt to carry out orders from both Davis and Johnston, Pemberton and his Army of Mississippi headed east to combine with Johnston’s forces gathering around Jackson, while remaining in contact with and covering Vicksburg.

Another order from Johnston changing their proposed meeting location caused Pemberton to turn around, and when he did, he collided with the full breadth of Grant’s army. Pemberton’s tactical errors and lack of coordination with Johnston led to Confederate defeats at Champion Hill (May 16) and even heavier losses at Big Black River Bridge (May 17).

General Johnston pressured Pemberton to abandon the city, but Grant forced nearly 30,000 Rebel soldiers back into the Vicksburg defenses on May 18, 1863. Pemberton was completely isolated. Grant launched two major assaults (May 19 and May 22) in an attempt to take the city, but Pemberton’s men repulsed them with heavy casualties, demonstrating the strength of the Vicksburg defenses. Grant’s force lay siege to the city and filled the twelve-mile ring around Vicksburg.

Pemberton and his soldiers endured a forty-seven-day siege, while soldiers and civilians were starved into submission. By the end of June, half of his men were out sick or in the hospital. Scurvy, malaria, dysentery, and other diseases cut their ranks. As the siege wore on, fewer and fewer horses, mules, and dogs were seen wandering about Vicksburg. Shoe leather became the last resort of sustenance for many adults.

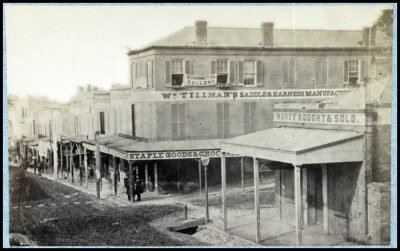

Image: Street view of Vicksburg

Image: Street view of Vicksburg

Corner of Washington and Clay

Fire Power

During the siege, Union gunboats lobbed more than 22,000 shells into the town, and artillery fire was even heavier. As the barrages continued, suitable housing became a rarity in Vicksburg. A ridge between the town and the rebel defense line provided lodging for some civilians. Others dug more than 500 caves into the yellow clay hills of Vicksburg, and it was often safer in these dugouts than elsewhere.

People did their best to make the caves comfortable, with rugs, furniture, and pictures. They tried to time their movements and foraging with the rhythm of the cannonade, sometimes unsuccessfully. Union soldiers gave the town the nickname of Prairie Dog Village. Despite the ferocity of the Union gunboat and artillery fire, less than a dozen civilians were killed during the siege.

Diarist Emma Balfour of Vicksburg later wrote:

I was up in my room sewing and praying in my heart … when Nancy [her slave girl] rushed up … warning of the falling shells, which sent people rushing into caves. Just as we got in [their cave], several … [shells] exploded … just over our heads, and at the same time two riders were killed in the valley. … As all this rushed over me and the sense of suffocation from being underground, the certainty that there was no way of escape, that we were hemmed in, caged – for one moment my heart seemed to stand still. Nearly all the families in town spent the night in their caves.

On the evening of July 2, Pemberton asked in writing if his four division commanders believed their men could “make the marches and undergo the fatigues necessary to accomplish a successful evacuation.” After receiving four votes of no, Pemberton asked Federal authorities to discuss terms of surrender.

On July 3, Pemberton sent a note to General Grant, who first demanded unconditional surrender. On second thought, Grant did not want to feed 30,000 hungry Confederates, and so he offered to parole all prisoners after the surrender. At 10:00 o’clock a.m. on July 4, 1863, Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg and his army – 2,166 officers and 27,230 men, 172 cannon, and almost 60,000 muskets and rifles. Terms were negotiated so that the Confederate soldiers would be paroled and:

…be allowed to march out of our lines, the officers taking with them their side-arms and clothing, and the field, staff, and cavalry officers one horse each. The rank and file will be allowed all their clothing, but no other property.

In the siege of Vicksburg and the battles leading up to it, Grant lost over four thousand men. The Southern military lost over thirty-five thousand soldiers. The Confederate surrender following the siege at Vicksburg, when combined with General Robert E. Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg the previous day, is sometimes considered the turning point of the war.

Pemberton was exchanged on October 13, 1863, and he returned to Richmond. There he spent some eight months without a command. Boredom and a desire to render faithful service prompted Pemberton to write to Jefferson Davis for an assignment “in any capacity in which you think I may be useful.”

Johnston, and Southerners in general, branded Pemberton a traitor for surrendering Vicksburg and accused him of causing the Confederate defeat by disobeying orders. Although the accusations plagued Pemberton for the rest of his life, it was the charge of incompetence that became inseparably attached to his reputation.

Unable to find a position commensurate with his rank, he resigned his commission as lieutenant general on May 9, 1864. Three days later, Davis offered him a commission as a lieutenant colonel in the artillery and he accepted. He commanded the artillery of the defenses of Richmond until January 9, 1865, and then he took a position as inspector general of the artillery and held it until the end of the war.

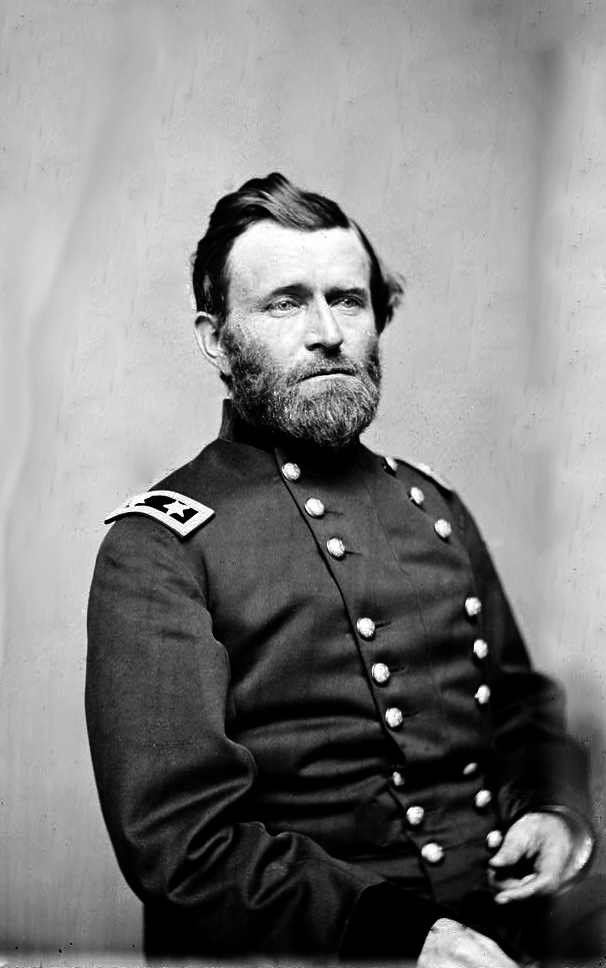

Image: Confederate General John C. Pemberton

Image: Confederate General John C. Pemberton

In his Civil War uniform

After the war, Pemberton’s mother bought John a farm named Harleigh near Warrenton, Virginia; he and Martha lived there from 1866 to 1876. The farm was not always prosperous, and he taught school in 1868-1869. After a while John became restless, and he and Martha moved to Allentown, Pennsylvania where he worked as a supervisor for the Iron Storage Department of the Pennsylvania Warehousing and Safe Deposit Company.

He later resigned and he and Martha moved to her hometown of Norfolk, Virginia, but they eventually moved to his hometown of Philadelphia.

John Clifford Pemberton died July 13, 1881 while visiting at the family home in Penllyn, Pennsylvania, a month before his 67th birthday.

Pemberton was scheduled to be buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, but there were protests by the families of several famous people already buried there: General George Meade (commander-in-chief at the Battle of Gettysburg), Thomas McKean (a signer of the Declaration of Independence) and Admiral John A. Dahlgren (head of the Union Navy’s ordnance department during the Civil War).

Pemberton was finally interred in an obscure section of the cemetery. A ground level plate was surreptitiously added noting that he was a ‘Confederate General Staff Officer.’

John C. Pemberton’s nephew, John Stith Pemberton, was a Confederate veteran and a druggist in Atlanta, Georgia, who invented Coca-Cola. The name was suggested by his bookkeeper Frank Robinson, who also had excellent penmanship and first scripted Coca-Cola into the flowing letters of their famous logo.

Martha Thompson Pemberton died August 14, 1907, in New York, at the age of eighty and was buried beside her husband.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: John C. Pemberton

Civil War Trust: John C. Pemberton

American Civil War: Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton

Vicksburg During the Civil War (1862-1863): A Campaign; A Siege