Abolitionist and African American Businesswoman

S. Epatha Merkerson plays Lydia Hamilton Smith in the 2012 film Lincoln, alongside Tommy Lee Jones as Thaddeus Stevens. The movie stars Daniel Day-Lewis as Abraham Lincoln and Sally Field as Mary Todd Lincoln. Merkerson owes much of her fame to her role as Lt. Anita Van Buren on the original Law and Order television series.

S. Epatha Merkerson plays Lydia Hamilton Smith in the 2012 film Lincoln, alongside Tommy Lee Jones as Thaddeus Stevens. The movie stars Daniel Day-Lewis as Abraham Lincoln and Sally Field as Mary Todd Lincoln. Merkerson owes much of her fame to her role as Lt. Anita Van Buren on the original Law and Order television series.

Lydia Hamilton Smith had a special relationship with U.S. Congressman Thaddeus Stevens. She became Stevens’ housekeeper in 1847, and for 25 years she managed his homes and businesses. Through their partnership she gained the skills and social contacts necessary to become a successful businesswoman after his death.

Lydia Hamilton was born in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on February 14, 1815, to an African mother and Irish father. She married a free black man named Jacob Smith and bore two sons but they separated before he died in 1852 and she raised the children alone.

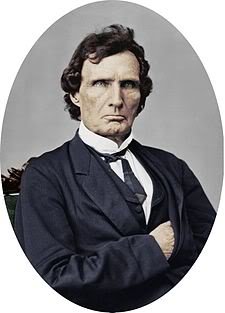

Thaddeus Stevens was born in Danville, Vermont, on April 4, 1792. He suffered from many hardships during his childhood, including a club foot. Stevens put himself through Dartmouth College, then moved to York, Pennsylvania, where he taught school and studied law. After admission to the bar, he established a law practice in Gettysburg in 1816.

After his skillful defense of a murderer for whom he pleaded insanity, an unusual defense at that time, he quickly acquired a lucrative practice and earned recognition as the leading figure of the Adams County bar. By shrewd purchase and by taking full advantage of sheriff’s sales, Stevens became the owner of so much property that by 1830 he was the largest taxpayer in Gettysburg.

During his days in Gettysburg, Stevens also assisted fugitive slaves who were traveling eastward from the city of Columbia, which was fourteen miles away and a key station on the Underground Railroad. He paid a spy to keep watch on slave catchers in the area. “I have a spy on the spies and thus ascertain the facts.”

Stevens served for several years in the Pennsylvania legislature, and delivered a brilliant speech that single-handedly saved the state’s infant public school system from an attempt to abolish it by the wealthy and devout. And he fought the state Constitution of 1838, which took away from black males the right to vote.

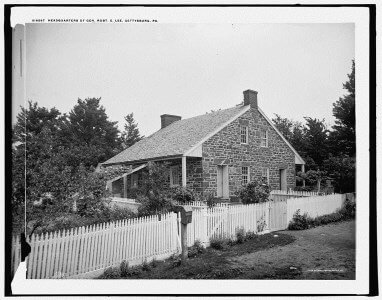

Thaddeus Stevens moved to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1842 and purchased property there in the early 1840s. He built a small addition connecting a saloon on Queen Street and his residence, and that is where he created his law office.

Stevens, whom Lydia Smith and her mother had known when he was an attorney and abolitionist in Gettysburg, offered her a position as his housekeeper in Lancaster. In 1847, Lydia moved her two boys to Lancaster to work for Stevens. She learned quickly how to manage a household with staff, as well as how to manage the household finances.

Lydia served as Stevens’ housekeeper, property manager and confidante for twenty years. Their partnership afforded her the opportunity to gain the skills and social contacts that helped her later become a successful businesswoman.

Stevens lived in the main house with his two orphaned nephews, Alanson and Thaddeus, whom they raised together, and who both later served in the Union Army. Lydia lived in “a one-story frame house on the rear of Mr. Stevens’ lot, fronting on South Christian street,” according to an article in the Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society.

Both Smith and Stevens were believed to have been involved in the antislavery movement while they lived in Lancaster. There is no proof that an underground cistern behind the Stevens home was used in the Underground Railroad, but a number of archaeologists who have visited the cistern discovered on the property have confirmed its probable use as a hideaway for runaway slaves. The fugitives might have been delivered in barrels to the tavern next door, which Stevens also owned, and hidden in the cistern until they could be passed on to another station.

There is ample documentation that Stevens regularly assisted black fugitives and paid spies to report on slave catchers active in the area. While less definitive information exists on Smith’s role in the Underground Railroad, research is continuing. However, the nature of their partnership, the proximity of her home to the cistern, and her connections in the local African-American community offer tantalizing clues.

While it was widely rumored during Stevens’ lifetime and afterward that he and Lydia were lovers, no evidence exists to support that. Stevens’ only comment on the matter was deliberately ambiguous: “I believe I can say that no child was ever raised, or so far as I know, begotten under my roof.” Years later, some of Stevens’ local friends and political associates acknowledged the domestic relationship, and Stevens’ political enemies were quick to make reference to it.

In any case, Stevens treated Lydia with great respect. He always addressed her as Madam, gave her his seat in public conveyances, and included her in social occasions with his friends. He hired Jacob Eichholtz to paint her portrait – an unusual sign of respect for a white lawyer to show a black housekeeper.

Image: Congressman Thaddeus Stevens

Image: Congressman Thaddeus Stevens

In the chaotic election year of 1848, Thaddeus Stevens won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives as an anti-slavery Whig, representing Lancaster County between 1849 and 1853. He opposed the Fugitive Slave Law and the Compromise of 1850. Lydia accompanied Stevens on his trips to Washington, DC, and was included in Stevens’ social gatherings.

When the new, anti-slavery Republican Party formed in the mid-1850s, Stevens helped organize it in Pennsylvania. Stevens rode the Republican Party into Congress again in 1858. He was renominated every two years thereafter through 1866, often running unopposed.

As a passionate believer in the principles of Radical Republicanism, the Great Commoner, as he was known, pushed for emancipation and black suffrage. The Radicals “were primarily responsible for turning the struggle into a war not only to preserve the Union but also to extinguish slavery.”

In 1860 Lydia purchased her home from Stevens and the lot adjacent to his, the first of several homes she owned in Lancaster – quite an accomplishment for a woman of color. She also purchased property in Washington, DC. Lydia Smith’s oldest son William died in 1860.

During the Civil War, Lydia’s son Isaac, a noted banjo player and barber, enlisted in the 6th U. S. Colored Troops in 1863. He and his regiment served primarily in Virginia.

In Congress Stevens was the Chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee, controlling the purse strings of President Abraham Lincoln’s war to preserve the Union, and was an early advocate Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. He also served as chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, and hence played a crucial role in Congressional funding for the Civil War. Following the war, he was chief architect of Reconstruction.

The three years after the Civil War ended were perhaps Stevens most prolific period. He proposed a bill to abolish slavery, the 13th Amendment. He ushered a bill through Congress that extended equal protection under the law to all citizens, the 14th Amendment; and he laid the groundwork for the passage of the 15th Amendment, which extended the right to vote to all male citizens.

After the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, driving a borrowed horse and wagon through Adams County, Lydia Hamilton Smith traveled around to the farms in the area, telling people of the tens of thousands of suffering men. She accepted donations of food and clothing for the wounded and, when the donations dried up, began spending her own money.

Each day, with her wagon heaped high, she rode to the field hospitals, where she distributed the articles to Union and Confederate soldiers alike. She continued to provide the makeshift hospital populations around Gettysburg with food, clothing and delicacies.

By 1868, Stevens was severely ill, and Smith hired nuns from a local convent to care for him in his last days. Smith and Thaddeus, Stevens’ nephew, stayed by his side until his death.

Congressman Thaddeus Stevens died in Washington, DC, on August 11, 1868. Even after death, he stood by his commitment to equality, having insisted on being buried in an African American cemetery. His gravestone proclaims “I have chosen this [burial site] to illustrate in my death the principle, which I advocated through a long life: Equality of man before his creator.”

Stevens had never married, and upon his death bequeathed to Lydia $5000 cash and some personal furnishings. With those funds and her property management experience, Smith operated her own boarding houses in Lancaster and Philadelphia.

Lydia became prosperous enough to purchase Stevens’ home and law office on South Queen Street in Lancaster and lived there for twenty years. She also bought a large boarding house across from the prestigious Willard Hotel in Washington, DC. She spent most of her time operating the establishment and earned a reputation as an astute businesswoman, but she returned often to Lancaster.

Lydia Hamilton Smith died in a hospital in Washington, DC, on February 14, 1884 – her 69th birthday. She was buried in St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery, at the church where she had long been a member.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Thaddeus Stevens

Lancaster County Historical Society

Lydia Smith – American Patriot and Inspiration

Editor:

I would like to have permission to re-print this article our quarterly journal, but your contact form is not functional.

Would you please contact me at the email address below?

Thank you,

James Knights,

BoD, Society for Women and the Civil War

This is the type of information that should be included in history books.

Thank you for this entry on Lydia Hamilton Smith. There are a few inaccuracies which I would like to point out in the hope that you can make some changes. These are in no particular order. When you write about Stevens assisting fugitives from slavery who are going eastward from Columbia they would have been headed to Lancaster, not Gettysburg. Columbia is approximately 14 miles west of Lancaster.

You claim that Jacob Eichholtz painted LHS’s portrait. I am recognized as the foremost authority on the work of Eichholtz and I can assure you there is no documented evidence that he painter her portrait, nor is the portrait of her in the style o Eichholtz. Several early writings made that assumption based on the fact that Eichholtz had painted Stevens’ portrait. Charles Bird King was the artist who painted Lydia Hamilton Smith’s portrait.

Stevens is buried in Shreiner Concord Cemetery which is not an African American cemetery. Rather, at the time of Stevens’ death, it was the only integrated cemetery in Lancaster and that is why Stevens chose to be buried there.

Also, the use of the cistern as a hiding place for fugitives from slavery is highly speculative and the National Park Service did not consider it sufficiently supportable, thus denying the site as an official designation as part of the Network to Freedom. That status was eventually conferred on the house at 45-47 South Queen Street, but it was based on documented evidence that the house had been instrumental in Underground Railroad activity, not based on the assertion that the cistern had served that purpose.

Finally, while it is possible that Smith originally lived separately from Stevens in Lancaster, after at least 1856 she almost certainly lived in the same house as he since many of their personal furnishings were intermingled at the time of his death.

Mr. Ryan-

I too noticed the error about Columbia and Gettysburg in the article. Lydia Hamilton Smith intrigues me and I am interested in her education as she was born in Gettysburg and Stevens was once head of the school board there. Did she go to public school in Gettysburg as a child? Stevens was an advocate for equality in education. She became a businesswoman, so I assume a high level of literacy.

Thomas-

Thank you for your post. Do you know the names (first and last) of Lydia’s parents. I found a half-sister in her will (from the Lancaster Historical Society) but no one seems to know her parents’ first names. Tim Black. ([email protected])

Thomas-

Thank you for your post. Do you know the names (first and last) of Lydia’s parents. I found a half-sister in her will (from the Lancaster Historical Society) but no one seems to know her parents’ first names.