Civil War Nurse and Wife of General E.R.S. Canby

Louisa Hawkins Canby, wife of Union General Edward Richard Sprigg (E.R.S.) Canby, was named the Angel of Santa Fe for her compassion toward the cold and wounded Confederate soldiers who occupied Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1862. She not only nursed the Rebel troops, but also showed them the location of the blankets and food her husband had ordered to be hidden before he and the Union troops left the city.

Louisa Hawkins Canby, wife of Union General Edward Richard Sprigg (E.R.S.) Canby, was named the Angel of Santa Fe for her compassion toward the cold and wounded Confederate soldiers who occupied Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1862. She not only nursed the Rebel troops, but also showed them the location of the blankets and food her husband had ordered to be hidden before he and the Union troops left the city.

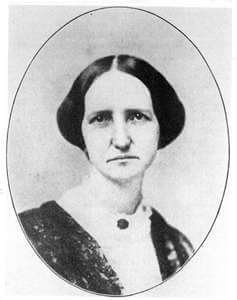

Image: Louisa Hawkins Canby

Early Years

Louisa Hawkins, was born December 25, 1818 at Paris, Kentucky to John and Elizabeth (Waller) Hawkins. Relatives and close friends always called her Lou. Raised in Crawfordsville, Indiana, at age 19 Lou met the dashing Edward Richard Sprigg (E.R.S.) Canby, a West Point cadet home on summer furlough. Like the Hawkinses, the Canbys had moved from Kentucky to Indiana.

Marriage and Family

After graduating from Georgetown Female College in Georgetown, Kentucky, Louisa married Lt. E.R.S. Canby at Crawfordsville, Indiana on August 1, 1839. Canby continued in military service, seeing combat in Florida during the Second Seminole War in the late 1830s and early 1840s and in the Mexican-American War in the mid-1840s. The couple had one child, Mary, who died young.

In his memoirs, General William Tecumseh Sherman recalls the arrival of the Canbys at Monterey, California in early 1849 where then-Major Canby succeeded Sherman as adjutant-general of the military Department of California. While the Canbys were in the territory, California applied for statehood. Lou Canby contributed to this effort by copying documents for the statehood convention and Major Canby arranged and indexed territorial records.

Lou then accompanied her husband to military posts in upstate New York, Wyoming and Utah in the 1850s. In 1859, while Colonel Canby was commander of Fort Bridger, Utah Territory (now in the state of Wyoming), the Canbys spent an enjoyable Christmas with Captain Henry Hopkins Sibley, who had graduated from West Point a year ahead of Canby.

Canby had also served on a court-martial trial that exonerated Sibley in 1858, and subsequently endorsed Sibley’s invention, the Sibley tent, which would be widely used during the Civil War. By 1860, Canby was posted in New Mexico and had found a large house in Santa Fe for his wife, where she could be comfortable while he was away campaigning against hostile Indians.

The Civil War

When the Civil War began, Colonel Edward R.S. Canby remained out west and was put in charge of defending an area that today covers the states of Arizona, New Mexico and the southern tip of Nevada. Canby assigned to himself the command of Fort Craig. Set in the rugged country of Socorro County, New Mexico, south of Sante Fe, it was one of eight forts situated on the primary north-south road in the Rio Grande Valley.

On December 20, 1861, Canby’s old friend now-Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley claimed New Mexico for the Confederacy. Following the Rio Grande River with 2,590 ill-equipped men, Sibley advanced north in February 1862, intending to take Fort Craig and the territorial capital at Santa Fe.

After capturing Union military installations to the south, on February 13, Sibley neared Fort Craig which was defended by around 3,800 Union soldiers under Colonel Canby. Unsure of the size of the approaching Confederate force, Canby employed several ruses to make the fort look stronger than it actually was. Sibley was afraid that Fort Craig might be too strong to be taken by direct assault, therefore he remained south of the fort and tried to entice Canby to attack.

After three days, Canby still did not leave his fortifications. Short on rations, General Sibley crossed the Rio Grande and moved up the east bank, intending to capture the ford at Valverde and sever Fort Craig’s lines of communication to Santa Fe. The Confederates camped to the east of the fort on the night of February 20-21.

Battle of Valverde

The Battle of Valverde took place upstream from Fort Craig at the Valverde Crossing. Alerted to the Confederate movements, Canby dispatched a mixed force of cavalry, infantry, and artillery under Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Roberts to the ford on the morning of February 21, 1862. Roberts sent the cavalry ahead to hold the ford where they met four companies of Sibley’s Confederates.

Depsite possessing a numerical advantage, the Union forces did not fire on the Confederate position until reinforcements arrived. When the Union force finally sent off the first volley, they discovered that the Confederates – largely equipped with pistols and shotguns which lacked sufficient range – were at a distinct disadvantage, but the Federals did not advance.

Learning of the standoff, Canby left Fort Craig with the bulk of his command. Arriving on the scene, he left two regiments of infantry on the west bank and pushed the remainder of his men across the river. Pounding the Confederate position with artillery, Union forces slowly gained the upper hand. Early in the afternoon, a company of lancers from the 5th Texas Rifles attacked, but they were met by heavy fire and soon withdrew. Ill (some said drunk), Sibley remained in camp.

Assessing the situation, Canby decided to turn the Confederate left flank. Seeing the Union assault forming, the Rebels attacked the Union right, but they were repulsed and the Union troops began advancing. However, the Confederates regrouped and surged forward in three waves. In fierce fighting, they succeeded in taking the big guns and shattering the Union line.

His position suddenly collapsing, Canby ordered a retreat back across the river, but many of his men had already begun to flee. Although many consider the battle to have been a Confederate victory, Union forces succeeded in holding Fort Craig, and they destroyed the Confederate supply train in the rear.

While Colonel Canby was fighting Sibley in the Battle of Valverde, Lou Canby was awaiting the outcome of the campaign at Santa Fe. Canby’s standing order to his troops was to destroy or hide not only weapons and ammunition but food, equipment and blankets prior to any retreat. Therefore when the Union Army and government evacuated Santa Fe, they burned or hid any supplies they were unable to carry with them.

Lou and several of the other officers’ wives made the bold decision to stay in Santa Fe instead of leaving with the army. On March 2, the Confederates captured Albuquerque and eight days later took Santa Fe. Bereft of rations, spare clothing and blankets, the men in gray, according to the Santa Fe Gazette, “rode, walked or hobbled into the city.” Among them were many wounded.

Angel of Santa Fe

Santa Fe residents were expecting them, having heard the booming of artillery that signaled a battle in progress. One woman took the lead in organizing preparations to receive and care for the Confederate wounded: Louisa Hawkins Canby. It was winter and snow was still falling in the region. The Confederates did not have enough blankets to keep their sick and wounded warm.

Taking pity on her husband’s enemies, Lou not only organized the officers’ wives to nurse the wounded and freezing soldiers, she showed them where food and blankets had been hidden. She converted the spacious Canby home into a hospital where Confederate surgeons dressed wounds and performed amputations on shattered limbs, without anesthesia. Lou herself served as nurse and hospital supervisor.

When some citizens objected to aiding the enemy, Lou said: “Whether friend or foe, the wounded must be cared for. They are the sons of some dear mother.” When she learned that some soldiers were left beside the road after the Battle of Glorieta Pass, unable to reach Santa Fe due to extreme hunger, exhaustion or loss of blood, Lou Canby drove her carriage along the route, delivering food, water and blankets to the needy men.

Since horse-drawn ambulances were unavailable to transport the men, she obtained several farm wagons in which she rigged hammocks of tent cloth, so that the wounded could travel in some comfort. One of the Texans reported that her ingenuity and dedication in this endeavor “doubtless saved many lives.”

After a week, the rebel troops began a withdrawal southward, leaving 100 of their critically wounded behind. Lou and the other women assisting in the hospital were relieved of their duties when Santa Fe was again occupied by U.S. military and civil officials. For her tireless efforts in aiding the suffering Texans, the gallant Mrs. Canby became known as The Angel of Santa Fe.

On April 1 or 2 General Sibley, who had been at Albuquerque most of this time, arrived at Santa Fe and personally met with Louisa. It is not known what transpired between them, but he probably thanked her for caring for his men and reminisced about their earlier encounters when he and her husband had been on the same side.

In a series of battles, Colonel Canby’s actions prevented Confederate expansion from Texas into the southwest, and he was promoted to brigadier general for his efforts.

In a series of battles, Colonel Canby’s actions prevented Confederate expansion from Texas into the southwest, and he was promoted to brigadier general for his efforts.

Image: General E.R.S. Canby

Back East

Soon after the defeat of the Confederates in New Mexico, General Canby was reassigned, and spent more than a year in bureaucratic service in Pennsylvania, New York and Washington, DC, sometimes as an unofficial administrative assistant to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Canby had a varied military career, serving in both important administrative positions and active battle service.

While he was a gifted administrator, there were some in the army, including General Ulysses S. Grant, who thought Canby was not aggressive enough in the field. In May 1864 he was promoted to Major General and placed in command of the Military Division of Western Mississippi. He and Lou eventually found a home in New Orleans where she stayed while he supported the Union’s impending defeat of Confederate forces.

Shortly before his forty-seventh birthday, General Canby was shot by a sniper while on an inspection tour up the Mississippi and White rivers. His wound was a painful but “through-and-through” gunshot to the pelvis. He arrived home the day after his birthday, and Louisa immediately put him to bed and nursed him back to health during the next month.

When the Confederacy fell in April 1865, General Canby accepted the surrender of the Confederate forces west of the Mississippi, which happened to include the remnants of Sibley’s brigade; although, by this time, Sibley himself had been court-martialed for dereliction of duty. Canby received the surrender of General Richard Taylor on May 4, 1865, and of General Edmund Kirby Smith on May 26.

Following the war, General E.R.S. Canby was retained by the army as one of only ten brigadier generals and served as military commander of various districts throughout the South. His first post was at Washington, DC, where General Grant came to hold Canby in great esteem for his knowledge and understanding of policy, law and army regulations.

Canby was then given a number of postings around the country including his service as military governor in Louisiana. This was followed by his appointment as Commander of the Fifth Military District, comprising the states of Delaware, Maryland, Alexandria and Fairfax, Virginia and Washington, DC. Additional postings in the Reconstruction South followed in Texas, and North and South Carolina.

Lou continued to follow General Canby wherever his military career took them. She greatly admired and respected her husband and, without children to occupy her time, she devoted her life to him. She was far more social than her husband and she always arranged for gatherings at the Canby residence. Some of Lou’s actions (like her heroic efforts to save the enemy at Santa Fe) complicated her husband’s life and career, but to his credit, he always steadfastly supported her.

In March 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant assigned Canby commander of the Department of the Columbia in the Pacific Northwest, which encompassed Oregon, Washington and Alaska in an effort to address issues with the Modoc Indians. The Canbys then moved to Portland, Oregon.

Relations between the Modoc tribe and the United States government were tense after a series of failed negotiations and treaties over native lands. The Modocs began attacking settlers in Oregon and northern California, which led to the Modoc War in 1872. After a number of false starts, Canby was able to arrange a meeting with the leader of the Modoc tribe, who was called Captain Jack.

Canby wrote frankly to Louisa about his misapprehensions over negotiations with the Modocs. His chief concern was that Captain Jack so feared treachery that he might respond in kind. Lou wrote back from Portland:

I think over all sorts of Modoc treachery till I am becoming a nervous, hysterical woman and will have to get away from Oregon to get over it.

Although he knew that the Modoc were volatile, Canby set up the meeting at a neutral site and went unarmed, hopeful that he could relieve the building tension between the two sides. During the peace talks, Canby stated that he did not have the authority to grant the Modoc their ancestral lands, the Modoc leader became enraged.

On April 11, 1873 Modoc leader Captain Jack killed General E.R.S. Canby.

General Canby was given a full military funeral in the west before his body was sent home. Former Civil War generals William Tecumseh Sherman, Phillip Sheridan, Irvin McDowell and Lew Wallace were in attendance, with McDowell and Wallace, Canby’s long-time friend, serving as pall bearers.

Lou found her husband’s death so unbearable that she spent a week in bed, but the people of Portland rallied to her side. When they discovered that her widow’s pension would be only $30 a month, they raised $5,000 as a gift to her. She accepted the money, but invested it and used only the interest to supplement her income. In her will, the full principal of $5,000 was returned to the people of Portland.

General Canby’s body was shuttled from place to place for more than a month before it reached Indiana and was finally buried at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis on May 23, 1873. With the support of her brother, Colonel John Hawkins, Lou devoted the last sixteen years of her life to promoting the memory of her husband and his many achievements. Lou was also well remembered for all of the lives she had touched during her military years.

Louisa Hawkins Canby died on June 27, 1889 at the age of 70, and was buried beside her gentleman general in Crown Hill Cemetery.

SOURCES

The Wallaces & the Canbys

Wikipedia: Louisa Hawkins Canby

American Civil War: Battle of Valverde