Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony

Roanoke Island is located between the Outer Banks and the mainland coast of North Carolina. It is well known as the site of the Lost Colony, where the first settlement of British colonists disappeared in 1587. It is not so well known for another colony that was established during the Civil War. The island was important militarily because it is located near the opening of two major sounds and is protected somewhat from the harsh weather in the Atlantic Ocean.

Roanoke Island is located between the Outer Banks and the mainland coast of North Carolina. It is well known as the site of the Lost Colony, where the first settlement of British colonists disappeared in 1587. It is not so well known for another colony that was established during the Civil War. The island was important militarily because it is located near the opening of two major sounds and is protected somewhat from the harsh weather in the Atlantic Ocean.

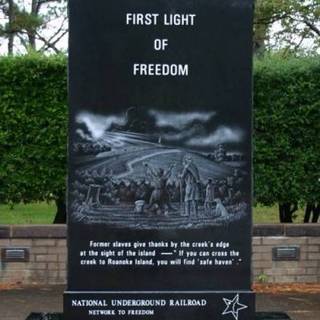

Image: Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony Monument

Fort Raleigh National Historic Site

In 2001, the Dare County Heritage Trail committee erected a marble monument to commemorate the Freedmen’s Colony of Roanoke Island. In 2004, the monument was added to the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

Soon after North Carolina seceded from the Union on May 20, 1861, the Confederacy established a military stronghold on the Roanoke Island. By the following winter, slaves hired by the Rebels had constructed three sand forts on the west side of the island, small batteries on the east side, and over a dozen large wooden barracks buildings.

But, even with the fortifications, General Henry Wise, the officer in charge, had a right to be concerned. He complained to his superiors that reinforcements would be needed to adequately defend the island, but he was told that the troops were needed elsewhere.

General Ambrose Burnside attacked on February 8, 1862 and after a brief but bloody battle, captured the island. Within several months, they also captured Fort Macon and Morehead City on the North Carolina coast.

When the Yankees arrived, there were about 200 slaves who had been working for the Confederates on Roanoke Island. Following the precedent established by General Benjamin Butler at Fortress Monroe in Virginia, Union officers did not return the slaves to their owners. They were considered contraband of war, and they were initially referred to as contrabands, and later freedmen or freedpeople.

Some of these male slaves returned to the mainland to get their wives and children and bring them to freedom. During their first days on the island, the former slaves sought shelter wherever they could find it, and many of them moved into the barracks that had been abandoned by the Rebels on the north end of the island.

Within weeks of the establishment of Union occupation, large numbers of slaves organized themselves into refugee camps at or near Union headquarters in the occupied areas. The early freedmen and freedwomen worked as laundresses, cooks, teamsters and porters for the Union officers and soldiers, and they lived undisturbed on the periphery of the Union camp.

Meanwhile, word that slaves who made it to Roanoke Island would be granted freedom spread rapidly to the rest of the island and northeastern North Carolina. Other slaves soon sought refuge in the Union camp.

By early April 1862, the refugees numbered approximately 250. As more slaves poured onto the island, Federal authorities grew concerned that sanitation problems in the makeshift camps would have adverse effects on the Union encampment. By late summer the number of refugees approached 1,000.

Roanoke Island was never attacked again, but Union troops continued to man the forts there. The island was used as a coaling station for gunboats. The soldiers and the freedmen ate well on clams and oysters from the surrounding waters.

Anticipating that a number of the black men would be recruited into the Union army, the military saw the need to provide a safe sanctuary for the families. In April 1863, Major General John G. Foster, Commander of the 18th Army Corps, ordered the Reverend Horace James, a Congregationalist minister who was serving as a chaplain in the Union army, to establish a colony of former slaves on the island. This site became known as the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony.

Although his headquarters was in New Bern, Reverend James felt a special fondness for Roanoke Island. He viewed it as more than a temporary shelter for the former slaves. Although the military took over the direction of the colony in the spring of 1863, the freedpeople continued to play a significant role in the direction of the group.

Once it was established that black men would be able to serve in the Union army, most of the island’s able-bodied men enlisted in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd North Carolina Colored Volunteers, which were later renamed the 35th, 36th and 37th U.S. Colored Troops.

Six teachers from the American Missionary Association and the National Freedman’s Relief Association made up the heart of the colony’s teaching corps, but at least 27 teachers, most from New England, worked on the island. They believed that education would prepare the freedpeople for citizenship.

The missionaries noted that all the able-bodied men were away from the island serving in the Union army. Freedmen from Roanoke Island fought in battles throughout the South, including Olustee, Petersburg and New Market Heights. Many died or sustained life-shattering disabilities.

Reverend Horace James, the superintendent of the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony, corresponded frequently with the officers of the American Missionary Association and the National Freedman’s Relief Association, describing his work in North Carolina.

In a letter dated June 27, 1863, Reverend James stated:

The location decided upon in which to commence this work, in North Carolina, is Roanoke Island. Its insular position favors this design, making it comparatively safe against attack. It is an island ten or twelve miles long, by four or five in breadth, well wooded, having an abundance of good water, a tolerably productive soil, a sufficient amount of cleared land for the commencement of operations, and surrounded by waters abounding in delicious fish. The time in which to do this work, is the present.

…an appeal is hereby made to all the friends of the New Social Order in the South, and in particular to those who believe that the solution of the negro question is the turning point of the war, for prompt and efficient help in the prosecution of our designs…Send contributions in cash, clothing, shoes, instruments, and supplies of every kind needed, to the undersigned at No. 1 Mercer street, New York, (offices of the National Freedman’s Relief Association).

Horace James,

Superintendent of Blacks for the Department of North Carolina

On September 5 1863, James wrote:

The colony is fairly on its feet. There are from eleven to twelve hundred Negroes now on the Island. They have come here from Plymouth, Elizabeth City, New Bern, and from the country around these and other points. For the present they are living in close quarters, too much huddled together in barracks formerly occupied by soldiers. But a large tract of well-wooded land has been laid off in streets running at right angles, and upon these streets lots of nearly an acre (40,000 ft.) have been assigned to the various families desiring them.

We have already staked out the outlines of an African village of grand proportions. It would gratify their friends at the north could they see the energy and zeal with which the freedmen enter upon the work of clearing up their little acre of land, by cutting the timber upon it, and preparing it for their rude log-house.

Let the unbeliever declare that the Negro does not desire his freedom, and has no wish to secure the privilege of owning personal property, and real estate. The axes which I sent on a month ago and which are now ringing merrily in the green woods of Roanoke give the lie direct to all their reasonings, and falsify all their assertions.

Horace James

In early 1864, James submitted a plan that showed 26 streets crossed by three avenues 50 feet wide, what amounted to a New England style village, on the north end of the island. He believed that providing small plots of land along with domestic production, shad fisheries and a sawmill would make the settlement self-supporting.

Families began building houses and gardens, about 600 in all, but there was not enough land to grow real crops. The people could not produce enough food and still had to get rations from the army. As more and more of the menfolk enlisted in the army, the freedwomen and their children were left to do the building and the farming.

In the spring of 1864, the Confederates recaptured Plymouth, North Carolina, and a new influx of freed blacks arrived on the island. The colony’s population swelled to more than 3,500 people, and the lack of housing and poor sanitary conditions caused the colony to begin a downward spiral.

Relations between the military and the freed families became strained. Union soldiers on the island began to take advantage of the colonists. They sometimes apprehended their rations. The blacks in the army complained that not only were they not paid often, if at all, but their families were suffering as well. Food rations were greatly reduced. People were going hungry.

As soon as the war ended, rations and supplies to the colonists were discontinued altogether. The freedmen who had been serving in the army came home, but there was no work for them, no way to buy food for their families. These men were no longer needed, and the government lost interest in the Freedmen’s Colony.

Reverend James appealed to President Andrew Johnson for aid. A month later, the president issued his ‘Amnesty Proclamation,’ which decreed that all property seized by Union forces during the war was to be returned to its rightful owner if they could prove title to it.

That was the beginning of the end of the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony. The land that had been given to the freedmen was taken away. Many of the them returned to the places they had escaped from and found work as farmers and sharecroppers.

In late 1865, the 30th U.S. Colored Infantry were ordered to dismantle the forts on the island. The Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony was abandoned by 1867. In 1870, the census counted only 300 blacks in 60 households.

Today, Virginia Tillett, a Dare County commissioner and assistant dean of continuing education at the College of the Albemarle, gives talks at schools and civic meetings about the colony, to keep the memory alive. Every autumn, she joins 20 volunteers to organize a festival. The women also collaborate with the Dare County Heritage Trail, a citizen committee.