Union and Confederacy Contest the High Ground at Gettysburg

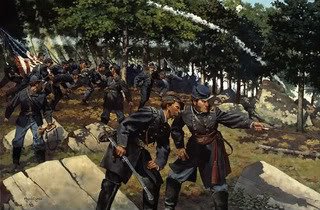

Image: Lions of the Round Top

Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863

By Don Troiani

After his troops had endured several charges, Union Colonel Joshua Chamberlain decided that a countercharge might catch the Confederates off guard. This painting depicts the 20th Maine’s desperate bayonet charge down the slopes of Little Round Top. At the center of the painting, Colonel Chamberlain of the 20th Maine confronts Confederate Colonel William Oates of the 15th Alabama.

Little Round Top

On July 2, 1863, Union Commander General George Meade ordered his chief engineer, General Gouverneur Warren, to climb the boulder-strewn hill locals called Little Round Top and assess the situation there. Warren noticed the flash of Confederate bayonets in the sun and realized that the Southerners were preparing to attack the boulder-strewn hillside.

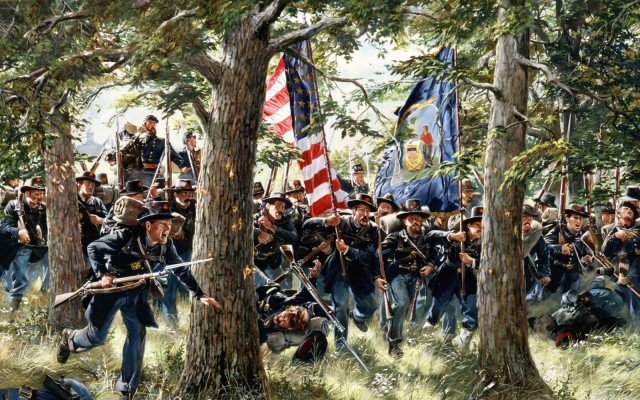

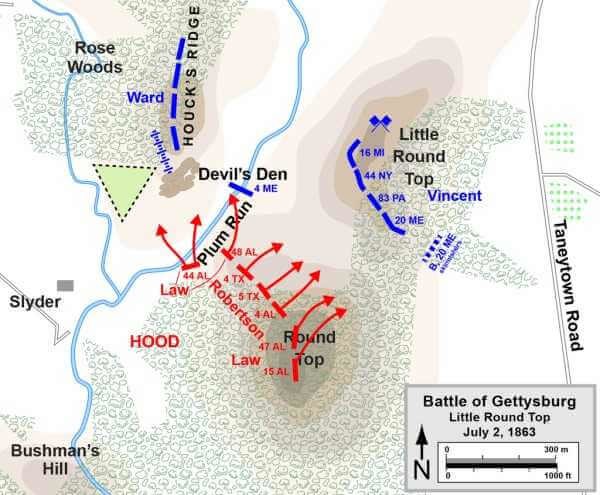

General Warren recognized the value of this high ground and called frantically for reinforcements to occupy the hill. Colonel Strong Vincent, commander of the Third Brigade of the First Division of the Union V Corps, responded. He arranged his four regiments atop the hill alongside the 16th Michigan, the 44th New York, the 83rd Pennsylvania, and the 20th Maine Infantry Regiment, which was at the far left end of the entire Union line.

Colonel Vincent told his regiments to take cover and await the inevitable Confederate assault; he specifically ordered Colonel Chamberlain of the 20th Maine to hold his position at all costs. If Chamberlain’s regiment were forced to retreat, the other regiments on the hill would be compelled to follow them, and the main Union left would have been outflanked.

Meanwhile, General Robert E. Lee had ordered General James Longstreet‘s Corps to launch a surprise attack the Federal left flank. The 15th Alabama Infantry Regiment was part of General Evander Law’s Brigade of General John Bell Hood‘s Division. Longstreet launched the engagement late in the afternoon of July 2.

The 15th Alabama Infantry Regiment – alongside the 4th and 47th Alabama and the 4th and 5th Texas Infantry regiments – had to march over rough terrain along the Emmitsburg Road. All the while they were receiving fire from Union sharpshooters at the Slyder Farm. This situation compelled the Confederates to detour around the Devil’s Den and over Big Round Top before they reached Little Round Top. By the time of the actual attack, these troops were thoroughly exhausted, having marched in the July heat more than twenty miles before they reached the field of battle.

Charge and Countercharge

Colonel William Oates, commander of the 15th Alabama assaulted the Federal troops positioned on the crest of Little Round Top. The first Union volley repulsed the 15th Alabama as they approached the Union line on the crest of the hill, and they withdrew briefly to regroup. Oates’ men then repositioned themselves further to the right, attempting to find the Union left flank.

Seeing the 15th Alabama shifting around his flank, Colonel Chamberlain ordered his troops to form a new line at an angle to meet the 15th Alabama’s flanking maneuver. Though they endured incredible losses, the 20th Maine held their line through five more charges over a ninety-minute period. Colonel Chamberlain decided that a countercharge was in order.

might catch the Confederates off guard.

Image: Map of the Battle at Little Round Top

Map of Little Round Top, showing the 15th Alabama’s initial position

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.posix.com/CW CC BY 3.0

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3116111

Colonel William Oates described the action in his memoirs, Gettysburg – the Battle on the Right (1878):

Vincent’s brigade … reached this position ten minutes before my arrival, and they piled a few rocks from boulder to boulder … and were concealed behind it ready to receive us. From behind this ledge, unexpectedly to us, because concealed, they poured into us the most destructive fire I ever saw. Our line halted, but did not break. The enemy was formed in line as named from their right to left. … As men fell, their comrades closed the gap, returning the fire most spiritedly.

I could see through the smoke men of the Twentieth Maine in front of my right wing running from tree to tree back westward toward the main body, and I advanced my right, swinging it around, overlapping and turning their left. I ordered my regiment to change direction to the left, swing around, and drive the Federals from the ledge of rocks, for the purpose of enfilading their line … gain the enemy’s rear, and drive him from the hill.

My men obeyed and advanced about half way to the enemy’s position, but the fire was so destructive that my line wavered like a man trying to walk against a strong wind, and then slowly, doggedly, gave back a little; then with no one upon the left or right of me, my regiment exposed, while the enemy was still under cover, to stand there and die was sheer folly; either to retreat or advance became a necessity. …

I again ordered the advance, knowing the officers and men of that gallant old regiment, I felt sure that they would follow their commanding officer anywhere in the line of duty. I passed through the line waving my sword, shouting, “Forward, men, to the ledge!” and promptly followed by the command in splendid style. We drove the Federals from their strong defensive position; five times they rallied and charged us, twice coming so near that some of my men had to use the bayonet, but in vain was their effort.

It was our time now to deal death and destruction to a gallant foe, and the account was speedily settled. I led this charge and sprang upon the ledge of rock, using my pistol within musket length, when the rush of my men drove the Maine men from the ledge. … About forty steps up the slope there is a large boulder about midway the Spur. The Maine regiment charged my line, coming right up in a hand-to-hand encounter. My regimental colors were just a step or two to the right of that boulder, and I was within ten feet. …

His [Colonel Chamberlain’s] skill and persistency and the great bravery of his men saved Little Round Top and the Army of the Potomac from defeat. … Great events sometimes turn on comparatively small affairs.

Colonel Oates always believed that if one more Confederate regiment had joined the assault, the attack would have been successful. His regiment would have turned the Union’s left flank and threatened the entire Army of the Potomac. If his regiment had taken Little Round Top, the Army of Northern Virginia might have won the Battle of Gettysburg. Since this engagement between the Mainers and the Alabamians proved to be such a pivotal event, the South might have had the chance to win the war.

The 20th Maine had performed valiantly and saved Little Round Top for the Union Army for the remainder of the battle. Colonel Joshua Chamberlain later said:

The two lines met and broke and mingled in the shock. The crush of musketry gave way to cuts and thrusts, grapplings and wrestlings. The edge of conflict swayed to and fro, with wild whirlpools and eddies. At times I saw around me more of the enemy than of my own men; gaps opening, swallowing, closing again with sharp convulsive energy; squads of stalwart men who had cut their way through us, disappearing as if translated.

All around, strange, mingled roar – shouts of defiance, rally, and desperation; and underneath, murmured entreaty and stifled moans; gasping prayers, snatches of Sabbath song, whispers of loved names; everywhere men torn and broken, staggering, creeping, quivering on the earth, and dead faces with strangely fixed eyes staring stark into the sky.

Colonel Joshua Chamberlain served in several battles after Gettysburg; he was wounded six times, cited for bravery four times, and had six horses shot from under him.

Colonel William Oates survived to fight another day, but he lost his right arm after being wounded near Petersburg, Virginia, which ended his active service.

Colonel Strong Vincent was mortally wounded while defending Little Round Top. He was carried from the hill to a nearby farm, where he lay dying for the next five days, unable to be transported home due to the severity of his injury. Vincent’s wife gave birth to a baby girl two months later, who died before reaching the age of one.

Vincent’s corps commander, General George Sykes, described the colonel’s actions in his official report of the battle:

Night closed the fight. The key of the battlefield was in our possession intact. Vincent, [General Steven] Weed, and [1st Lieutenant Charles] Hazlett, chiefs lamented throughout the corps and army, sealed with their lives the spot intrusted to their keeping, and on which so much depended. … General Weed and Colonel Vincent, officers of rare promise, gave their lives to their country.

SOURCES

Civil War Trust: Defense of Little Round Top

Wikipedia: 15th Regiment Alabama Infantry