First Lady of the United States

Ida Saxton McKinley, wife of William McKinley, 25th President of the United States, was First Lady from 1897 to 1901. She and her husband developed a unique way of coping with her epileptic seizures during her public appearances, and the love they shared during the early years of happiness endured through more than twenty years of illness.

Ida Saxton McKinley, wife of William McKinley, 25th President of the United States, was First Lady from 1897 to 1901. She and her husband developed a unique way of coping with her epileptic seizures during her public appearances, and the love they shared during the early years of happiness endured through more than twenty years of illness.

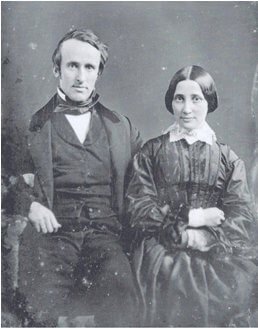

Image: Ida McKinley

Photograph from the 1896 Presidential Campaign

Early Years

Ida Saxton was born June 8, 1847 in Canton, Ohio, the second of three children born to Katherine DeWalt and James Saxton, a prominent Canton banker. The Saxtons were a prominent family in Canton: Ida’s grandfather founded the Ohio Repository, the first newspaper in Canton, and her father was a well respected banker and successful businessman.

A graduate of Brooke Hall Female Seminary in Media, Pennsylvania, Ida was refined, charming and strikingly attractive. She was also an intelligent, strong and independent young woman. These traits earned a position at her father’s bank as a clerk, a position then usually reserved for men. She eventually gained enough experience and knowledge to manage the bank when her father left the city.

William McKinley was born on January 29, 1843, in the small town of Niles, Ohio. He studied at a school run by the Methodist seminary in his hometown of Poland, Ohio, and then entered Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania in 1860. He attended Allegheny for only one term, however, because of illness and financial difficulties.

McKinley in the Civil War

When the Civil War began in 1861, William joined the Twenty-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry. The young private proved himself on the battlefields in West Virginia and at South Mountain, where his regiment lost heavily, and especially at the bloody Battle of Antietam, where he brought up hot coffee and provisions to the fighting line. For this he was promoted to second lieutenant on the September 24, 1862.

McKinley was promoted to first lieutenant in February 1864, and for his services at Winchester was promoted captain on July 25, 1864. He was on the staff of General George Crook at the battles of Opequon, Wisher’s Hill and Cedar Creek in the Shenandoah valley, and on March 14, 1865 he was breveted major of volunteers for gallant and meritorious services.

McKinley also served on the staff of Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, future President of the United States. His relationship with Hayes, whom he considered his mentor, remained constant throughout his life. Four years of army life changed him from a pale and sickly lad into a man of superb figure and health.

Marriage and Family

Ida Saxton met William McKinley at a picnic in 1867. Ida was a slender young lady with sky-blue eyes, fair skin and masses of auburn hair. William was a handsome young lawyer with a promising future. They began courting after she returned from a Grand Tour of Europe in 1869, and fell deeply in love.

Ida Saxton, aged 23, married William McKinley, aged 27, on January 25, 1871 at the First Presbyterian Church in Canton, forming a loving and devoted marriage. Following the wedding, the couple attended a reception at the home of the bride’s parents before leaving on an eastern wedding trip.

The McKinleys had two daughters. Their first, Katherine, was born on Christmas Day in 1871. In April 1873, Ida gave birth to their second daughter, who died at the age of four months. Ida descended into a deep depression. Phlebitis and epileptic seizures overcame her fragile health, and her condition worsened when Katherine died of typhoid fever in 1875. The McKinleys had no more children.

Epileptic seizures are episodes that can vary from brief and nearly undetectable to long periods of vigorous shaking. Seizures tend to recur, and have no immediate underlying cause. Medical science at the time could not cure or even successfully explain epilepsy, so because of many misconceptions about it, such a diagnosis meant that the patients and their families were socially stigmatized. Because of this, many families kept the illness a closely guarded secret and the McKinleys followed this practice.

Because Ida’s seizures could last just a few seconds or put her into a coma, McKinley responded to her condition with total devotion. He learned what to expect when a seizure became imminent and was ready to quickly pull out a handkerchief and drape it over her face, hiding her expressions. Doctors could only reduce the severity of the seizures with a sedative.

Political Partner

Ida’s illness did not prevent the McKinleys from seeking a political career for William, and in 1877 when he began his first term in Congress, Ida accompanied him to Washington. Ida enjoyed social events, but was also content to stay at the hotel where they lived. While McKinley was tending to congressional business, Ida always had an attendant nearby, as she contentedly embroidered or knitted countless pairs of bedroom slippers, which were sometimes auctioned off at charity events.

Despite poor health, Ida was actively involved in her husband’s political career as U.S. congressman, and then governor of Ohio. She travelled with him whenever possible, and served as First Lady of Ohio from 1892 through 1896. McKinley was greatly devoted to Ida and accommodated his work to suit her needs.

Though afflicted by a condition that had to remain a secret to prevent social shame, Ida refused to remain secluded. Her seizures sometimes happened in public – one occurred at McKinley’s inaugural ball after he was elected Governor of Ohio – but they were adept at hiding them. After the 1887 death of their father, Ida’s sister Mary Barber learned the details of her sister’s epilepsy, and when McKinley had to be away, she provided the necessary care when Ida suffered a seizure.

As interest in McKinley as a presidential candidate increased, his advisors expressed concern that Ida’s health might present a problem. To prove she would not be a detriment to her husband’s political plans Ida planned a large party to celebrate the McKinleys’ 25th wedding anniversary, successfully playing hostess to 600 people over 6 hours.

During the 1896 Presidential election, unfounded rumors began circulating about Ida’s illness, so a campaign biography was written about her and added to her husband’s biography. For the first time, a First Lady’s image appeared on a campaign pin. Ida was at William’s side as much as possible, and he ran what was to be called his Front Porch Campaign primarily from Canton. Ida did travel to Chicago to purchase a Washington wardrobe.

First Lady of the United States

Ida McKinley assumed the position of First Lady to President William McKinley from 1897 to 1901, witnessing the important events of his presidency that included the Spanish-American War and the Annexation of Hawaii. After an exhausting day with all the Inaugural events, she suffered a seizure while leading the Grand March at the Inaugural Ball and was removed to a cloakroom unconscious. When she woke up she was back at the White House.

While at the White House, the McKinleys did not let Ida’s health interfere with her role as First Lady, but they changed some White House traditions to accommodate Ida’s condition. She dressed beautifully at formal receptions, but received guests while seated in a blue velvet chair holding a fragrant bouquet, to politely refrain from shaking hands.

While at the White House, the McKinleys did not let Ida’s health interfere with her role as First Lady, but they changed some White House traditions to accommodate Ida’s condition. She dressed beautifully at formal receptions, but received guests while seated in a blue velvet chair holding a fragrant bouquet, to politely refrain from shaking hands.

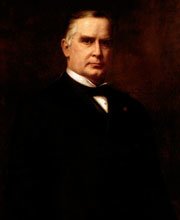

Image: President William McKinley

The President insisted that the First Lady be seated next to him at state dinners rather than at the other end of a long table. He was always watching for signs of an impending seizure. If one came on, he would momentarily cover Ida’s face with a large handkerchief to conceal her contorted features. When it passed, he resumed whatever he was doing as if nothing had happened. In those days, guests were discreet and newspapers silent about what were called her fainting spells.

Excerpt from Ida McKinley: The Turn-of-the-Century First Lady through War, Assassination, and Secret Disability by Carl Sferrazza Anthony:

Despite the greater understanding of neurological disorders at that time, a vast percentage of the general public would have ignorantly judged Mrs. McKinley to be better suited for an institution than the White House had they known she lived with epilepsy….

From the moment she arrived in Washington, when she refused the use of a wheelchair and strode throught the train station, Ida McKinley defied expectations. While acknowledging her chronically recurring immobility without shame, she sacrificed none of the traditional First Lady duties but rather adapted her condition to it, hosting weekly receptions, welcoming visiting delegations, attending state dinners, stopping to speak with tourists….

Never interested in the domestic tasks women were expected to manage, she worked to help secure employment for unmarried women who had to support themselves. She not only went public with her support of a woman’s right to vote but to higher education as well. She proved her belief that racial equality would be achieved through education bu committing to underwrite the private school costs for a family of several children.

The First Lady was especially close with her younger sister Mary Barber. During McKinley’s presidency (1897-1901), newspapers so frequently made reference to Mary Barber that the public came to know her by name. While she was a frequent visitor to the White House, Mary lived with her husband and seven children at the Saxton-McKinley House in Canton, Ohio.

The First Lady’s brother George Saxton was murdered by gunshot by a jilted lover in October 1898. Five shots were fired, three of which entered his body, and Mrs. Anna George has been placed under arrest on suspicion of the murder. The McKinleys attended the funeral in Canton. Mary Barber thereafter assumed the responsibility for managing the properties and investments made by their father which she and the First Lady inherited.

Ida McKinley traveled to California with the President in May 1901. As the trip itinerary proceeded along the Pacific coastline north from Los Angeles, a small cut in Ida’s index finger became infected. Her body temperature spiked dramatically and it soon became clear that she had blood poisoning.

The presidential party established itself at a private home in San Francisco.

For almost two weeks, McKinley conducted his presidency from here while the First Lady struggled to survive. The world’s attention focused on the house, from which regular bulletins were issued to update the public on her condition. Once it was clear her health had returned, the presidential party returned to the White House where she rested for another month.

Assassination

The First Lady often traveled with the President. She accompanied him to Buffalo, New York for the Pan-American Exposition in September 1901. Her appearance on the grandstand where he would deliver his opening remarks were captured by a movie camera, making Ida McKinley the first incumbent First Lady to be seen on film. Ida visited Niagara Falls with the President, but avoided all of the Exposition venues due to the large crowds there.

The First Lady was therefore not with her husband when he was standing in a public receiving line at the Temple of Music on September 6, 1901. The President was shaking hands with the public when he was shot by anarchist Leon Czolgosz, who had lost his job during the economic Panic of 1893 and turned to anarchism, a political philosophy whose adherents had recently killed foreign leaders.

Regarding McKinley as a symbol of oppression, Czolgosz felt it was his duty as an anarchist to kill him. Czolgosz shot McKinley twice as the President reached to shake his hand in the reception line at the temple. One bullet grazed McKinley; the other entered his abdomen and was never found. The President thought immediately of Ida, telling his secretary: “My wife, be careful how you tell her. Oh, be careful.”

During the eight subsequent days when it seemed he might recover, Ida McKinley held his hand and displayed remarkable physical and emotional strength. Once it was clear that the President would not survive, the First Lady’s physician and those treating the President permitted her to see him one final time, but prevented her from being with him in the moments before his death.

At 2:15 a.m. on Saturday, September 14, 1901, President William McKinley died. Although she bore up well in the days before the president’s death, Ida could not attend his funeral. The President was interred at the Werts Receiving Vault at West Lawn Cemetery in Canton until his memorial was built. Ida visited his burial site almost daily.

After President McKinley’s death, the former First Lady lost much of her will to live. Her health eroded as she withdrew to the safety of her home and memories in Canton, where she was cared for by her younger sister, Mary Barber.

Ida McKinley died May 26, 1907, surviving the president by less than six years. She was buried next to him and their two daughters in Canton’s McKinley Memorial Mausoleum.

Image: Saxton-McKinley House, Canton, Ohio

Image: Saxton-McKinley House, Canton, Ohio

In addition to growing up in this house, Ida and her husband lived here from 1878 through 1891, while McKinley served in the United States House of Representatives. The house has been restored to its Victorian splendor and is now part of the complex forming the National First Ladies Historic Site.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Ida Saxton McKinley

First Lady Biography: Ida Mckinley

The White House: Ida Saxton McKinley

Women in History: Ida Saxton McKinley