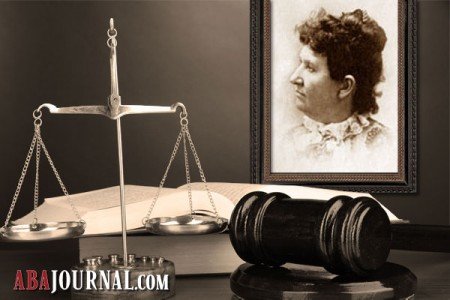

First Woman College President in the United States

Frances Willard was an author, educator, public speaker, social reformer and suffragist. A pioneer in the temperance movement, Frances Willard is also remembered for her contributions to higher education. From the time she assumed presidency of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in 1879 until her death, Willard used her powerful position to pursue her broad vision for sweeping social reforms to benefit women, including women’s suffrage, women’s economic rights, as well as prison, education and labor reform.

Frances Willard was an author, educator, public speaker, social reformer and suffragist. A pioneer in the temperance movement, Frances Willard is also remembered for her contributions to higher education. From the time she assumed presidency of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in 1879 until her death, Willard used her powerful position to pursue her broad vision for sweeping social reforms to benefit women, including women’s suffrage, women’s economic rights, as well as prison, education and labor reform.

Willard captivated the imaginations and mobilized the sentiments of countless women. Her vision progressed to include federal aid to education, free school lunches, unions for workers, the eight-hour work day, work relief for the poor, municipal sanitation and boards of health, national transportation, strong anti-rape laws and protections against child abuse.

Childhood and Early Years

Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard was born September 28, 1839 to Josiah Flint Willard and Mary Thompson Hill Willard on a small farm in Churchville, near Rochester, New York. Frances had two siblings, Oliver and Mary, and her cousin was educator Emma Willard. When she was three, the family moved to Oberlin, Ohio.

In 1846 the family moved again, this time to Janesville, Wisconsin, where her father had purchased a large farm. Wisconsin became a state in 1848, and Josiah Flint Willard was elected to the legislature. During the family’s stay in Wisconsin, they converted from Congregationalists to Methodists, a Protestant denomination that placed an emphasis on social justice and service to the world.

The Willards were dedicated to the education of their children. Mary Willard had studied at Oberlin College in the days when few women attended college, and she taught her children at home until the town of Janesville established its own school in 1853. Frances was recognized as exceptional, and was given the best education possible at that time. She also spent many hours writing a journal, perfecting her writing skills.

When she was seventeen, Frances left home for the first time to attend the Milwaukee Seminary, a respected school for women teachers where Mrs. Willard’s sister taught. But Mr. Willard wanted Frances to attend a Methodist school, so in 1858 the family moved to Evanston, Illinois, where she attended Evanston College for Ladies. There she completed her college degree, graduating in 1859 as class valedictorian.

Career in Education

From the time of her college graduation until 1868, Frances Willard taught at a variety of institutions, including teaching science at Pittsburgh Female College and at Genesee Wesleyan Seminary in New York. In 1861, Willard became engaged to Charles Fowler, a divinity student, but she broke off the engagement only months later.

During the Civil War years, Willard suffered a series of personal crises: both her father and her sister Mary died, and her brother Oliver became an alcoholic. Her family underwent financial difficulties due to her brother’s excessive drinking and gambling, and Frances became her mother’s sole support.

In 1868 Willard became friends with a young woman named Kate Jackson, who convinced her wealthy father to finance the two of them on a two-year tour of Europe. Willard climbed the Pyramids of Egypt, and far above the others on an eminence she said: “Let us have plain living and high thinking.” Her European experience was fundamental in establishing her values and opinions concerning women.

After her trip, Willard returned to Evanston to become president of Evanston College for Ladies in 1871. When that school merged with Northwestern University, she was appointed Dean of Women of the Woman’s College of Northwestern University, and Professor of Aesthetics in the university’s Liberal Arts college.

Willard is credited with introducing an innovative approach to women’s education. Under her plan, women could either remain entirely within the structure of the Ladies College or branch out into traditional male fields through classes at Northwestern University. They might even earn a degree from Northwestern; but the women at all times belonged to, and were under the authority of, the Ladies College. This program, which she set up, was later adopted at Radcliff and Barnard Colleges.

Her college was a huge success, but her stay there was short lived. A new president came to Northwestern in 1871 – Charles Fowler, Willard’s ex-fiance. Fowler set about to undercut her program, saying that the women were under the authority of the University and no longer under the Ladies College. The male students began harassing Willard and did their best to humiliate her in the classroom.

The issue became a political one and was argued in the press. Fowler was made to appear the liberal wishing to give women freedom while Willard was painted as the conservative. In the end Willard’s position was not politically strong enough to withstand the pressure, and she resigned in 1874. She later described those years as the most difficult of her life.

Relationships

In 1861 Willard became engaged to a divinity student, Charles Fowler, who was described as “intelligent, handsome, audacious of speech, and strong minded” – a man who would later become the president of Northwestern University, editor of the Christian Advocate and a Methodist bishop. Marriage to Fowler would have provided Willard with entry into the public arena as the wife of a prominent man.

In her autobiography, Willard is very reticent about her reasons, but after a few months she broke the engagement. There is evidence that she understood that marriage would mean giving up her independence. She wrote:

What it might be to give oneself up so fearlessly – somewhat as we do to God. To feel the supremacy of a loftier, stronger nature… Yet I do not feel quite sure that it is a possibility of my nature ever to give myself up.

Frances Willard never married. Following her engagement to Fowler, she had another attachment but it did not lead to an engagement. She also wrote in her biography of a secret love that she thought would sometime be revealed, but so far that remains a mystery.

In the nineteenth century, loving female friendships were an acceptable form of social interaction. As professional women took up careers and found themselves without husbands and children, a partial solution was found in intimate friendships with other women. These relationships, while passionate, were not sexual.

Frances Willard biographer Ruth Bordin (Frances Willard: A Biography) writes:

The new professional woman also found the support of these special relationships of crucial importance in carrying out her work. The spectrum of choices meant that in the nineteenth century no one looked askance at the… young married woman who was not so exclusively involved with her husband that she could not cling to the companionship of a special woman friend who had shared the confidences of her youth… Victorian society provided many avenues in which supportive emotional relationships could take place.

Willard’s primary emotional ties, although they seem not to have been explicitly homosexual, were to women – not the least was her own widowed mother around whom she centered her life. There were numerous women with whom she spent time, traveled and corresponded. They gave one another unselfconscious emotional intimacy and financial assistance, and were political allies. Anna Gordon was her living and traveling companion, and her private secretary for 22 years.

Career in Social Reform

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was founded in 1874 in response to widespread concern that American society was breaking down. Alcohol abuse was rampant. There were no legal limits on the alcoholic content of whiskey, and it was often lethal. The main objective of the WCTU was to persuade all states to prohibit the sale of alcoholic beverages. Annie Wittenmyer was its first president.

Frances Willard knew alcohol abuse first hand. Her own brother was troubled by alcoholism, and both of his sons became alcoholics. She assumed responsibility for her nephews after her brother’s death. One nephew was able to overcome his addiction; the other could not. Her beloved brother’s losing battle with alcoholism clearly demonstrated alcohol’s power to destroy the lives of individuals and their families.

Willard was offered the presidency of the Chicago WCTU, and accepted that position in March 1874. Her tireless efforts for prohibition included a fifty-day speaking tour in 1874, an average of 30,000 miles of travel a year, and an average of four hundred lectures annually for a ten year period, mostly with her longtime companion Anna Gordon.

In January 1877, Willard resigned as the president of the Chicago WCTU because national WCTU president Annie Wittenmyer objected to Willard’s push to get the organization to support woman suffrage as well as temperance. Willard also resigned from her other positions with the national WCTU and began lecturing for woman suffrage. In 1878, Willard won the presidency of the Illinois WCTU.

President of the WCTU

Frances Willard ran and was elected president of the National WCTU in 1879 and remained in that office until her death in 1898. By that time she was well known as a powerful advocate of women’s suffrage – so much so that she was opposed in her election by those who felt she would concentrate the WCTU’s considerable influence on women’s rights. This did not happen. Willard did not neglect temperance; neither did she renounce feminism.

Under her leadership, the WCTU grew to be one of the largest organizations of women in the 19th century, with 27,000 regular members and another 25,000 in junior auxiliaries. Each year Willard published an address in which she proposed a plan of work and ideas for the betterment of society. During the year, she spoke and traveled and used her influence to accomplish the items on her agenda. She supported herself by lecturing until the WCTU granted her a salary in 1886.

In fighting for temperance, she depicted the liquor industry as ridden with crime and corruption, men who drank alcohol as victims for succumbing to the temptations of liquor, and women, who had few legal rights to divorce, child custody and financial stability, as the ultimate victims of liquor.

Nothing concerning women escaped Willard’s attention. During her tenure (1879-1898), the WCTU succeeded in bringing about temperance education in schools, and supported prison reform and the abolition of prostitution. According to Willard, the men who patronized a prostitute should be equally guilty under the law as the prostitute who served him.

On the subject of rape, Willard wrote:

It is by holding men to the same standard of morality that society shall rise to higher levels, and by punishing with extreme penalties such men as inflict upon women atrocities compared with which death would be infinitely welcome. …in Massachusetts and Vermont it is a greater crime to steal a cow than to abduct and rape a girl, …in Illinois rape is not considered a crime, it is a marvel… that we go the even tenor of our way, too delicate, too refined, too prudish to make any allusion to these awful facts, much less take up arms against these awful crimes.

The WCTU worked for the kindergarten movement, prison reform, the eight-hour day, model facilities for dependent and handicapped children, federal aid to education and vocational training. It circulated a petition gaining 8 million signatures worldwide, asking governments to stop the sale of opium and other narcotics. Willard protested fashion because women were suffering serious illness in an attempt to achieve thin waists. After repeated efforts, Willard finally organized the World’s WCTU in 1883 and was made its president.

Late Years

Willard attended the International Council of Women meeting in Washington, DC, laying the permanent foundation for the National Council of Women. She published her autobiography, Glimpses of Fifty Years, in 1889, and in 1892 founded a magazine, The Union Signal. In her later years, she became a socialist, calling for government ownership and control of all factories, railroads and theaters.

Throughout her career, Willard was as adamant in professing her Christian faith and as she was her feminism. She felt no pressure to chose one over the other. In 1895 when Elizabeth Cady Stanton published the Woman’s Bible (a controversial book that implicitly rejected key portions of Scripture), Willard was careful to disassociate herself from it – although she and Stanton were in agreement on most other issues.

Late in 1897, she visited her birthplace in Churchville, New York; then Oberlin, Ohio. She next traveled to her hometown of Janesville, Wisconsin, where she gave her last public address in the Congregational Church of Janesville in January 1898. Early in 1898, Willard and her party went to New York City as guests of the Hotel Empire previous to sailing for England and France. After two weeks in the city, she became seriously ill with influenza.

Frances Willard died quietly in her sleep on February 17, 1898 at age 58. (Some sources say the illness that killed her was pernicious anemia, which had been the source of several years’ ill health.)

At the time of her death, Frances Willard was the most famous woman in America. Flags flew at half-mast across the country. Her body was transported by rail from New York to Chicago, pausing for services along the way like a presidential funeral train. In Chicago, 30,000 persons filed by her casket in one day. She was buried there in Rosehill Cemetery.

Statements published at the time of her death are revealing. Edward Wheeler of the Literary Digest wrote:

She was an awakener of women to the possibilities of true womanhood and she has probably done more than any other person who ever lived to bring to those of her own sex the world over, an adequate realization of their own powers.

Today, many people have never heard of Frances Willard, while her contemporaries, who were lesser lights during their lifetime – Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Emma Willard – have immediate name recognition. Frances Willard was, however, the first woman represented among the illustrious company of America’s greatest leaders in Statuary Hall in the United States Capitol.

Key Publications

• Woman and temperance, or the work and workers of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, 1883

• Glimpses of fifty years: the autobiography of an American woman, 1889

• How to Win: A Book for Girls, 1886

• Woman in the Pulpit, 1888

• Do everything: a handbook for the world’s white ribboners, 1895

• A Wheel within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, 1895

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Frances Willard

About Women’s History: Frances Willard

Frances Willard: America’s Forgotten Feminist

American National Biography Online: Frances Willard

Hi,

Frances was definitely not straight, and it is sad to read this information that completely devalues the complex and rich relationships Frances had with women. The intimacy and beauty of the relationships at the time should not be diminished in any way. The journals between Frances and Mary make it quite obvious just how attracted to and infatuated with Mary Frances was. While Frances should be most known for her accomplishments, the true extent of her identity should not be hidden. There is way too much evidence that displays the closeness between Frances and Mary– that most definitely was different than friendship.