Wife of Union General John Gibbon

Frances North Moale Gibbon, called Fannie by family and friends, was the Darling Mama of General John Gibbon’s Civil War letters. From Gettysburg he wrote: “God has been good in protecting me from so many dangers. Both [General John] Reynolds and Stephen Weed were killed, the latter yesterday.”

Frances North Moale Gibbon, called Fannie by family and friends, was the Darling Mama of General John Gibbon’s Civil War letters. From Gettysburg he wrote: “God has been good in protecting me from so many dangers. Both [General John] Reynolds and Stephen Weed were killed, the latter yesterday.”

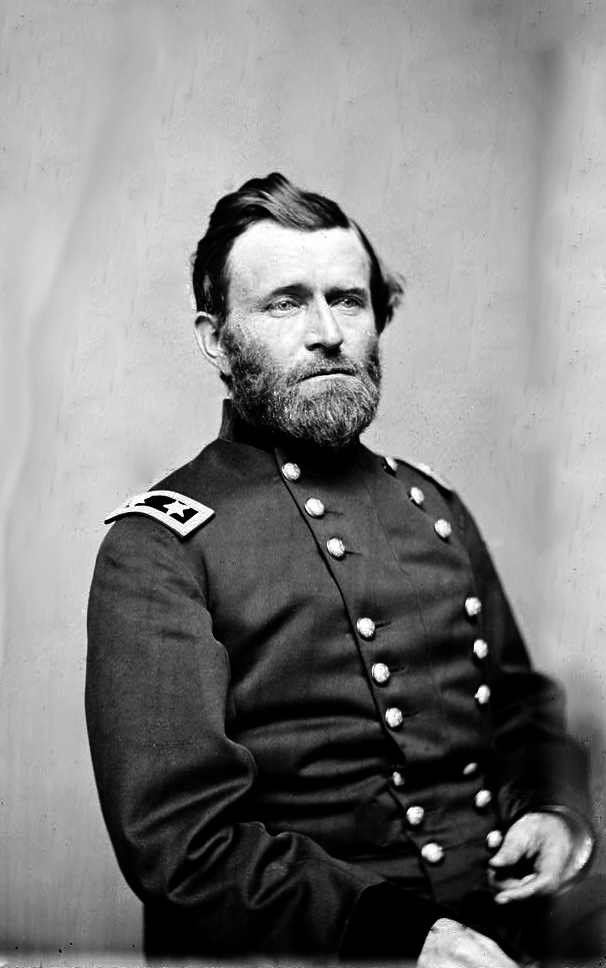

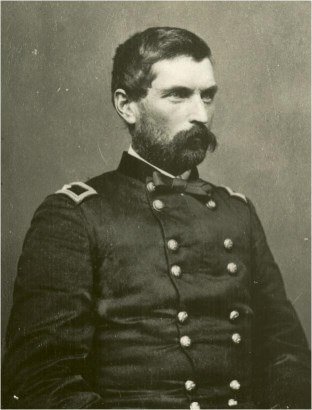

Image: General John Gibbon

Husband of Frances Gibbon

John Oliver Gibbon was born on April 20, 1827, in the Holmesburg section of Philadelphia, the third son and the fourth of seven children of Dr. John Heysham Gibbon and Catherine (Lardner) Gibbon. Although the family name was originally “Gibbons,” the doctor dropped the s, so that by the time Doctor Gibbon had married and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania, the change was permanent. Catherine and the children followed Dr. Gibbon to Charlotte, North Carolina, where he had accepted an appointment as chief assayer at the United States Mint.

While living in Charlotte, young John Gibbon was selected to be a cadet of the United States Military Academy at West Point, thus beginning a career as a professional soldier in the US Army that would last until his retirement almost fifty years later. In 1842, at the tender age of fifteen, Gibbon entered the Academy. Among his classmates were such later notables as Orlando Willcox, A. P. Hill, Ambrose Burnside, Romeyn Ayres and his life-long friend Henry Heth, who fought with General Robert E. Lee in the Civil War.

Cadet Gibbon was an average student who soon proved deficient in his studies. Faced with the choice of being dismissed or repeating a year, Gibbon chose the latter and consequently did not graduate until July 1, 1847, ranking 20th in a class of 38. He received a commission as a brevet second lieu¬tenant in the 3rd Artillery.

Sent off to Mexico City and Toluca in the waning months of the Mexican War, the new officer missed the battles in which other West Point graduates won praise and fame. While graduates of the class of 1846 – his original classmates – emerged with brevets to the ranks of first lieutenant, captain, and even major, John Gibbon’s only promotion was to the permanent rank of second lieutenant in the 4th Artillery on September 13, 1847.

After a brief assignment at Fort Monroe, Virginia, in 1848, Lieutenant Gibbon was transferred to Fort Brooke, Florida, where he spent several years with the force assigned to keep the Seminole Indians in check. While stationed at Fort Brooke, the lieutenant had the good fortune to serve with Captain John C. Casey, whose fair and considerate treatment of the Florida Indians made a lasting impression on the younger officer. Gibbon would later write of his men¬tor, “He never deceived them; never told one of them a lie; and never made a promise he did not fulfill, if within his power.”

Promoted to first lieutenant on September 12, 1850, Gibbon joined Light Battery B of the 4th Artillery, and spent the next two years on the Texas frontier, first at Ringgold Barracks and then with the garrison at Fort Brown. Following an extended leave of absence and a stint on court-martial duty, he was again ordered to Florida to assist in the removal of the remaining Seminoles.

On September 25, 1854, First Lieutenant John Gibbon began his duties as Assistant Instructor of Artillery and Cavalry Tactics at West Point, an indication of his ability in that military art.

John Gibbon married Frances (called Fannie) North Moale on October 16, 1855. John, a Protestant, had patiently courted Miss Moale, a Roman Catholic, for two years, until he finally overcame her father’s opposition to the marriage. John cleverly asked the Moales’ Roman Catholic parish priest to perform the ceremony, and that must have tipped the scale in his favor.

Gibbon took his new wife with him to West Point. They had four children: Frances Moale, Catharine (Katy) Lardner, John, Jr. (who died as a toddler) and John S. Gibbon. Their two daughters were born at West Point.

Over the ensuing months, Gibbon replaced Fitz John Porter as Artillery Instructor, and was made post quartermaster on September 16, 1856; he performed dual assignments throughout that school year. He continued to act as quartermaster until August 31, 1859, with one brief absence to serve on a board testing the merits of new breech-loading rifles.

Although his career as an artillery instructor ended on July 5, 1857, Gibbon reworked his class notes into a definitive artillery textbook that was widely used for several decades. Published by D. Van Nostrand in 1859, The Artillerist’s Manual quickly went into a second edition and was adopted by the War Department, which purchased and issued hundreds of copies. The New York Herald had kind words in a notice of the publication, concluding, “The book may well be considered as a valuable and important addition to the military science of the country.”

On November 2, 1859, John Gibbon was promoted to captain and assigned to command Battery B, 4th Artillery. In June 1860 Captain Gibbon took Fannie and the girls in a mule-drawn army ambulance across the Plains to Camp Floyd, Utah Territory, where he was part of the peacekeeping force in the Mormon country. A prolific writer and illustrator, Gibbon recorded his family trip for posterity in Adventures on the Western Frontier (Indiana University Press, 1994).

In the summer of 1861, he received orders to abandon the post and return with the 4th Artillery to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, some 1,200 miles away. The column arrived there on October 8, 1861, by which time the Civil War had begun.

Gibbon and Fannie, like many, were forced to choose between families in North Carolina and Maryland and honoring the oath he had taken as an officer of the United States Army, knowing that three of his brothers, two brothers-in-law, and a cousin would join the Confederate Army. Gibbon obviously decided to remain loyal to the Union.

Throughout the war, John Gibbon would be out of contact with his family in North Carolina; he would not receive or send any communication with his brothers in the Confederate Army. Nor did he blame those in his family who felt their loyalties were to the Confederacy. He accepted their decision as peacefully as he accepted his own decision to follow his conscience. At the end of the war, Gibbon resumed his relationship with his family, as though the four-year violent interruption had never existed at all.

Captain John Gibbon arrived at Washington, DC, on October 29, 1861, and was appointed chief of artillery for General Irvin McDowell‘s division, a post he would hold until the following May. His responsibilities included not only training his own Battery B, its depleted ranks soon filled with volunteers from infantry regiments, but also instructing three volunteer batteries.

Captain Gibbon demonstrated “a natural talent for dealing with the volunteer soldier, whose possibilities, as well as limitations, he appreciated from the first,” and the four batteries soon won reputations for dependability unsurpassed in the Army of the Potomac. Gibbon’s initial success in training artillery volunteers led to a nomination as brigadier general of volunteers, a step which other West Point graduates had already made. But Gibbon’s confirmation was held up because he had no political friends in Washington.

Finally, on May 2, 1862, the artillery captain received a commission as brigadier general of United States Volunteers and was assigned to command an infantry brigade composed of four regiments. General Gibbon made an enviable name for himself and his brigade, subsequently named the Iron Brigade, in hard-fought battles at Bull Run on August 3, Brawner Farm on August 28 and South Mountain on September 14, 1862.

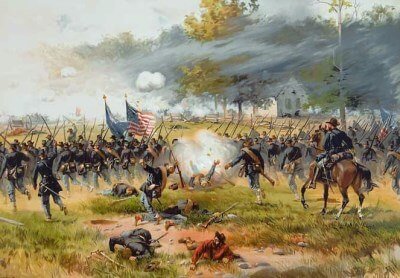

In Miller’s cornfield at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, Gibbon’s black-hatted, frock-coated westerners again proved their worth. After Antietam, Gibbon wrote to Fannie, “I am as tired of this horrible war as you are, and would be perfectly willing never to see another battlefield.” Throughout most of the war, Fanny and the children remained in Maryland.

Charge of the Iron Brigade

Charge of the Iron Brigade

By Thure de Thulstrup

Near Dunker Church

Battle of Antietam

In November, 1862, General Gibbon moved to division command with the Second Division in his friend General John Reynolds’ First Corps. On December 13, he was ordered to support General George Meade’s attack on the Confederate right flank at Fredericksburg, Virginia. Although a portion of Meade’s division managed to break though the enemy line, and some of Gibbon’s men captured a few Confederates, the attack did not have the strength to succeed. Near the end of the fight, Gibbon was struck in the left wrist by a shell fragment, which broke a bone in his hand and inflicted a painful wound in his wrist.

Within three days Gibbon was in Washington, where he was visited by President Abraham Lincoln, and a few days later was in Baltimore with his family. After a period of convalescence, he returned to the army, and was assigned to command the Second Division of General Darius Couch‘s Second Corps.

At Chancellorsville in May 1863, General Gibbon discovered just what his division was made of, when they supported attacks by John Newton’s Sixth Corps division on the heavily fortified Confederate position behind the stone wall at the bottom of Marye’s Heights.

Personal tragedy struck Gibbon on June 16 when his twenty-three-month-old son, John, died suddenly.

Gibbon at Gettysburg

After a short visit home, Gibbon was back with the army by the end of the month, and in pursuit of General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia, which had crossed into Maryland. The Army of the Potomac, with its new commander, General George G. Meade, finally encountered Lee’s army near the small Pennsylvania crossroads town of Gettysburg early on the morning of July 1.

An aide described the general as he appeared in July 1863:

He is compactly made, neither spare nor corpulent, with ruddy complexion, chestnut brown hair, with a clean-shaved face, except his mustache, which is decidedly reddish in color, medium-sized, well-shaped head, sharp, moderately-jutting brows, deep-blue, calm eyes, sharp, slightly aquiline nose, compressed mouth, full jaws and chin, with an air of calm firmness in his manner. He always looks well dressed.

At about noon on July 1, 1863, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, the new Second Corps commander and one of Meade’s most trusted lieutenants, was sent forward to Gettysburg, acting as headquarters’ eyes. Gibbon temporarily took Hancock’s place as corps commander and marched the men north towards the town. Early in the evening, Gibbon and the Second Corps reached the battlefield in the area of the Round Tops.

After encamping for only a short time, at dawn on the morning of July 2, Gibbon led his division to a position along Cemetery Ridge just south of the town’s Evergreen Cemetery. The terrible fighting of the second day left Gibbon’s division relatively untouched, but it was obvious to all that the contest would resume again the next day.

On the evening of July 2, as relative calm settled over the field of carnage, General George Meade called his generals to his headquarters at the Leister House. As temporary commanding officer of the Second Corps, Gibbon participated in this famous Council of War.

As the junior officer present, Gibbon had to give his opinion first as to what tactics should be followed on the following day. When asked his opinion by General Daniel Butterfield, Meade’s chief of staff (who was recording the generals’ remarks), Gibbon replied, “Remain here, and make such corrections in our position as may be deemed necessary, but take no step which even looks like retreat.”

Years later Gibbon recalled:

Before I left the house, Meade made a remark to me that surprised me a good deal, especially when I looked back upon the occurrence of the next day. By a reference of the votes in council, it will be seen that a majority of the members were in favor of acting upon the defensive and awaiting the action of Lee.

In referring to the matter, just as the council broke up, Meade said to me, “If Lee attacks tomorrow, it will be in your front.” I asked him why he thought so, and he replied, “Because he has made attacks on both our flanks and failed, and if he concludes to try again, it will be on our centre.” I expressed a hope that he would, and told General Meade with confidence that if he did, we would defeat him.

The following morning, July 3, was relatively quiet in Gibbon’s sector. His division headquarters servant prepared coffee and appropriated a tough old rooster, which was made into a stew. General Meade joined the group to partake of the meal, leaving after a short time to return to matters of importance. The remaining diners lolled for a spell, and it was probably then that Gibbon wrote the following short note to his wife, describing the battle of the previous two days.

General Gibbon Letter to Fannie:

Head Quarters, Near Gettysburg

July 3d 1863 10 1/2 o’clock AM

My Darling Mama:

We had a great battle yesterday commencing at 4 pm and continued long after dark. The enemy attacked us, and after the hardest fighting I have seen, were repulsed at all points. Today there has been more or less artillery and picket firing going on, but no general fight. And both armies are tired enough to remain quiet for some hour longer. We can await longer than the rebels, and I hope before many hours are over Lee’s army will be so disabled as to render any further harm in this part of the country impossible. God has been good, dear Mama, in protecting me from so many dangers. Both [General John] Reynolds and [General] Stephen Weed were killed, the latter yesterday.Kiss the dear children for me and write often.

Yours ever

JG

After a time, Gibbon heard the sound of a single Confederate cannon, and the entire area was alive with shells and explosions. Gibbon was forced to run toward the front lines – the orderly bringing up his horse had been killed. As the general reached the crest of the hill Gibbon found himself,

in the most infernal pandemonium it has ever been my fortune to look upon. Very few troops were in sight and those that were, were hugging the ground closely, some behind the stone wall, some not, but the artillerymen were all busily at work at their guns, thundering out defiance to the enemy whose shells were bursting in and around them at a fearful rate, striking now a horse, now a limber, and now a man.

When another orderly finally came forward with the general’s horse and information that the enemy was coming, Gibbon as he later recalled,

hurriedly mounted and rode to the top of the hill where a magnificent sight met my eyes. The enemy in a long gray line was marching toward us over the rolling ground in our front, their flags fluttering in the air and serving as guides to their line of battle. In front was a heavy skirmish line which was driving ours in on a run. Behind the front line, another appeared, and finally a third, and the whole came on in a great wave of men, steadily and stolidly.

Pickett’s Charge had begun. During the attack, Gibbon rode up and down his line, encouraging his men. While trying to get the left flank of his division to move out and catch the Confederate right in an enfilade fire, Gibbon was struck by a bullet in the left shoulder, which broke his scapula, inflicting a wound that would disable him for several months.

Gibbon later said, “I soon began to grow faint from the loss of blood, which was trickling from my left hand.” Turning command over to Brigadier General William Harrow, Gibbon was removed to a field hospital near Rock Creek. Lieutenant Haskell later visited him and told him the results of the battle. As Gibbon had promised Meade following the council of war the night before, Lee had been stopped.

Once again, Gibbon returned to Baltimore for recuperation with his family. After four months of convalescence, he returned to duty as commander of the Draft Depot at Cleveland on November 15, 1863, but within a week he was transferred to command the Draft Depot at Philadelphia, a post much closer to his wife and children, who were then living in Baltimore with Fannie’s family. General Gibbon resumed command of his division on March 21, 1864.

General John Gibbon had a solid reputation in the Army of the Potomac. Colonel Theodore Lyman, an aide at army headquarters, wrote two descriptions of the general that show how he was perceived during the Overland Campaign of 1864. In a letter describing affairs after the fighting in the Wilderness, Lyman wrote:

By the roadside was Gibbon, and a tower of strength he is, cool as a steel knife, always, and unmoved by anything and everything… the most American of Americans, with his sharp nose and up-and-down manner of telling the truth, no matter whom it hurts.

Gibbon participated in the bloody Overland Campaign, leading his men at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, North Anna, Totopotomoy, Cold Harbor, and various operations during the siege of Petersburg. On June 7, 1864, Gibbon was promoted to major general of US Volunteers, a rank which would normally entitle him to command a corps, but that honor did not come until the following January.

If Gettysburg was the apex of Gibbon’s career, the ebb was Reams Station (August 25, 1864). The First and Second Divisions had been sent to Reams, eight miles south of Petersburg, to tear up the Weldon & Petersburg Railroad. For most of the day, Hancock’s men had repulsed Confederate attacks led by Gibbon’s old friend, CSA General Henry Heth. At 5 pm, the Rebels broke through the Union line and took possession of the entrenchments. Caught in a withering crossfire, the Second Corps lost nearly 2000 men captured or missing, nine pieces of artillery, and seven regimental colors. Some of the regiments surrendered en masse without firing a shot.

On January 15, 1865, Gibbon was assigned to command the Twenty-fourth Corps in the Army of the James, and he led that unit in the final operations against the Petersburg defenses, including the pursuit of General Lee to Appomattox. Gibbon was the senior officer of three commissioners, selected by General Ulysses S. Grant, in charge of arrangements for the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House, where Gibbon also supervised the printing of the parole forms.

The war was over, and it was a time to renew old friendships that had been separated by the color of their uniforms and different ideals.

When General Gibbon was mustered out of the volunteer service on January 15, 1866, he reverted to captain, the highest rank he had attained in the Regular Army. On January 30, he began a

seven-month assignment as a member of an artillery board, which worked to restructure that arm of the service after the muster out of the volunteers. As a consequence of that reorganization, Gibbon was promoted to colonel of the 36th Infantry on July 28, 1866.

On December 1, 1866, Colonel Gibbon was ordered west to take command of the post at Fort Kearny, Nebraska, beginning a career in the West that would last until his retirement.

He served at a number of posts during the remainder of his military service: Fort Kearny until May 1867; Fort Sanders, Dakota Territory, until December 1868; transferred to the Seventh Infantry on March 15, 1869; Camp Douglas, Utah, until 1870; Fort Shaw, Montana Territory, until 1872; superintendent of the recruiting service in New York City during 1873; Fort Shaw again until 1879; Fort Snelling, Minnesota, until 1883; Fort Laramie, Wyoming Territory, in 1883; commander of the Department of the Platte in 1884.

Image: General Gibbon and Chief Joseph, leader of the Wallowa Valley Nez Perce, met at the Battle of the Big Hole in 1877. Here, they posed together in 1889, twelve years after Joseph’s epic retreat.

Image: General Gibbon and Chief Joseph, leader of the Wallowa Valley Nez Perce, met at the Battle of the Big Hole in 1877. Here, they posed together in 1889, twelve years after Joseph’s epic retreat.

John Gibbon’s name was closely associated with two major Indian campaigns during his frontier service: the Sioux Campaign of 1876 and the Nez Perce Campaign of 1877. In the former, Gibbon commanded the Montana Column, which rescued the survivors and buried the dead of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer‘s 7th Cavalry after the battle with Teton Sioux and Northern Cheyenne Indians on the Little Bighorn River. In the latter, although his force was outnumbered, Gibbon attacked Chief Joseph’s band of Nez Perce at Big Hole, Montana Territory. The battle was actually a tactical defeat for Gibbon’s small force, but the losses inflicted on the Nez Perce helped bring the campaign to a swift conclusion.

The Gibbon family would cross the nation many times in the next 30 years as the general’s career flourished. Gibbon was promoted to brigadier general of the Regular US Army, on July 10, 1885, and thereafter served at Vancouver Barracks, Washington Territory, as commander of the Department of the Columbia.

Officers’ housing improved over the years, too, until at the apex of Gibbon’s career, the general and his family moved as the first residents into an 8,000-square-foot Victorian mansion built for the commander of the Department of the Columbia at Vancouver Barracks, Washington Territory.

Fannie entertained to her heart’s delight as important visitors frequented their home for teas, hops, balls and masquerades. U.S. presidents, senators and business magnates travelling West called on John and Fanny Gibbon. A general’s wife held sway over social, ethical and political matters within the Department.

Fannie Gibbon and her two daughters supported the women’s right to vote. Upon retirement, John wrote an article for Harper’s Weekly “In Defense of Women’s Right to Vote.” Like Fannie, the general believed in women’s rights but he did not join in his wife’s voting marches and campaigns.

While living in Washington Territory (1886-1889), Fannie and all women of majority age enjoyed equal voting rights with male voters in county and local elections. Women shared positions on school boards and paid taxes. They lost this right when Washington Territory became a state, but the state was one of three in the nation to extend community property rights to women.

Throughout his post-Civil War career, John Gibbon devoted much of his time to writing. By 1885, he had completed a manuscript of his wartime experiences, although the volume, entitled Personal Recollections of the Civil War, was not published until 1928, and then only after some editing by his daughter, Frances Moale Gibbon. The book has since become accepted as a classic account of the war.

The general also wrote more than two dozen articles for various magazines on a number of topics. Only in his description of the wonders of the Yellowstone National Park did Gibbon seem at a loss for words to adequately describe the sights of the region. Those West Point instructors who had declared him deficient in grammar would have been proud of his literary legacy.

While Gibbon would be remembered primarily for his military campaigns, Charles A. Woodruff recalled some of the traits displayed by John Gibbon the man:

He loved nature, was fond of books, yet devoted to rod and gun, and encouraged every manly sport. Children always looked upon him as their personal friend, and for woman he had a respectful admiration, and was her earnest champion. A better husband and father I never knew. He was a model of faithful devotion, tender, thoughtful, and most considerate. He was of a very social disposition, loved to be in the midst of friends, old or young, and while he could keep up his end of the conversation with anecdote, reminiscence, or argument, was also a good listener.

Following his retirement on April 20, 1891, John Gibbon settled into the family home at 239 West Biddle Street in Baltimore. He remained active during his retirement, dividing his time between speaking to veterans groups across the country, visiting battlefields, and writing articles.

On his retirement, John Gibbon wrote a poem which says, in part:

Nations and horses and soldiers as well,

Have their downs and their ups, their heaven, their hell;

Nations and horses run their course, then expire;

Soldiers run theirs, for a time, then retire.

The bugle no longer shall call them to arms;

No longer the ‘long roll’ to them sounds alarms;

Once bearded as pards and full of strong ‘damns’

They peaceful become, yes as peaceful as lambs.

To farewells I’m averse. I don’t like ‘goodbyes’

They make the voice tremble, they moisten the eyes;

‘Tis better to flank them, it brings on no fight;

So with a God bless you, I bid you good night.

At 3:40 pm on February 6, 1896, a few months short of his seventieth birthday, the soldier who had survived Confederates and Indians finally succumbed to pneumonia.

On February 7, 1896, readers of the Baltimore Sun were met by the simple headline: GENERAL GIBBON DEAD. The obituary stated that the general had died at his rented home at 239 West Biddle Street in Baltimore, and that he was survived by his wife and two children. The article also described in detail Gibbon’s military career.

The general’s remains were conveyed to Arlington National Cemetery, where he was buried on February 10, near the old camps where he had drilled his batteries in 1861. Survivors of the Iron Brigade, the only brigade he had ever commanded, took up a collection for his monument. Although it might be considered modest by some standards, it overlooks the capital of the country to which he had devoted his life.

Fannie and John Gibbon enjoyed a remarkably close companionship throughout their married lives. Fannie died a few years after her husband, but like many 19th century wives, the date of her death has not been found.

SOURCES

John Gibbon

Brigadier General John Gibbon

General John Gibbon Biography

Commanders-in-Chief Biographies

General John Gibbon at Gettysburg

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Union Second Corps, Second Division

John Gibbon: The Man and the Monument

General John Gibbon’s Brief Breach at Fredericksburg