First Woman to Work as a Professional Artist

Fanny Palmer (1812-1876) was the first woman in the United States to work as a professional artist, and to make a living with her art. She produced more Currier and Ives’ prints than any other artist, and she was the only female in a business that was dominated by men. Painting was not considered a suitable occupation for a woman.

Fanny Palmer (1812-1876) was the first woman in the United States to work as a professional artist, and to make a living with her art. She produced more Currier and Ives’ prints than any other artist, and she was the only female in a business that was dominated by men. Painting was not considered a suitable occupation for a woman.

Image: A small, frail woman, Fanny Palmer stood bent over her work for so many years in the same position that she developed a widow’s hump in her later years.

Early Life

Frances (Fanny) Flora Bond, the daughter of an attorney, was born in 1812 in Leicester, England, and she received an excellent education at a private school for young ladies in Leicester run by Mary Linwood, who was famous for her crewel embroidery. There, Fanny learned to draw.

When she was 20, Fanny married Edmund Seymour Palmer, who was employed as a gentleman’s gentleman (a male servant). In the following years Fanny gave birth to a daughter and a son. After Edmund lost his job, they suffered financial problems.

Career in Art

In 1842 they established a lithography business in Leicester, with Fanny as the artist and lithographer and Edmund as the printer. To create a lithograph, the artist uses a set of greasy crayons or pencils to draw the artwork onto a large, thick slab of limestone, which is then treated with various chemicals.

During the printing process, the ink adheres to the greasy substance of the image, while the background has been treated to repel ink. The image is then printed onto paper or other suitable material. In addition to other works, the Palmers published a series of picturesque views, Sketches in Leicestershire (1843), but the business eventually failed.

By 1844, Fanny and Edmund had saved enough money to move to the United States. They settled in New York City, where they set up another lithography and printing business which they named F & S Palmer. There they produced a great variety of lithographs for other publishers, as well as in their own name. They lithographed some of the flower prints for A. B. Strong’s book, The American Flora.

In 1847 they published The New York Drawing Book: Containing a Series of Original Designs and Sketches of American Scenery, No. 1, hoping to create a series of such books that would save the business. Although it was priced at only 25 cents, it did not sell well and the series ended with No. 1. This business also failed, leaving the Palmers and their two children in dire straits.

In 1849, they moved to Brooklyn, where Edmund took a job running a local tavern and often drank up most of his income. In the book Currier & Ives: Printmakers to the American People, author Harry Peters describes Edmund Palmer as:

He was fond of shooting, even fonder of drinking, and had no interest in any kind of work. As time went on, his son Edmund Jr. became a handsome second edition of his father.

Hired by Nathaniel Currier

In 1851, Fanny Palmer was hired as a staff artist by Nathaniel Currier, and she became the family breadwinner. She would travel in a carriage to New Jersey, Long Island, and other nearby places where she would sketch all types of rural and suburban settings, but, most of her artwork came from descriptions in books, daguerreotypes and, in the latter part of her career, photographs. She sometimes used her husband and his dogs as models for her Long Island hunting and wildlife scenes.

Fanny Palmer was the first woman in the United States to make her living as a full-time artist. She is also generally regarded as the foremost woman lithographer of her time. All lithographs were produced on limestone printing plates on which the drawing was done by hand and printed one by one. A stone often took over a week to prepare for printing.

Palmer’s earliest lithographs were printed in black and white and then colored by hand. As new techniques were developed, she began to produce full-color lithographs that gradually became softer, and her picturesque panoramas of the American landscape more closely resembled paintings.

Currier and Ives

In 1857, Nathaniel Currier’s brother-in-law James Ives became a partner in the business, and the name was changed to Currier and Ives. Shortly thereafter, Ives – an artist in his own right – began to redraw the figures in Fanny Palmer’s pictures. Needing the income to support her family, she remained with the company.

The firm of Currier and Ives became the most prolific and successful publisher of lithographic prints in mid-nineteenth century America, and their lithographs represented every phase of American life: hunting, fishing, whaling, city life, rural scenes, winter scenes, historical scenes, ships of all kinds, railroads, gold mining, commentary on life, portraits and still lifes.

In 1859, a drunken Edmund Palmer died after falling down a flight of stairs in a Brooklyn hotel, leaving Fanny the sole support for her children, her granddaughter and her sister, Maria Bond. Nathaniel Currier remarked that Edmund’s death was the best thing that ever happened to Fanny.

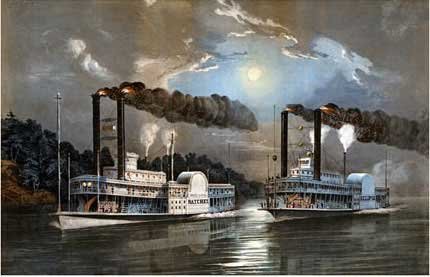

Image: A Midnight Race on the Mississippi

Image: A Midnight Race on the Mississippi

Artist: Fanny Palmer

Drawing: H.D. Manning

Printmakers: Currier & Ives

Although Fanny Palmer never traveled more than 100 miles outside of New York City, she created many scenes she had never witnessed, like these steamboats on the Mississippi River, working from a drawing by H.D. Manning. This moonlit scene depicts a race between the Natchez (left) and the Eclipse on the Lower Mississippi in 1854, in which the Eclipse proved victorious.

By the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Fanny had become one of America’s most prolific and versatile printmakers, producing hundreds of prints for Currier and Ives which portrayed a wide range of subjects, including farm and suburban scenes, sporting and marine prints, still life, literary subjects, panoramic views of steamboats, railroad trains, the Civil War and the settling of the American West.

A large body of Palmer’s work at Currier and Ives were entirely original; drawn or painted and lithographed by her as well. In some cases they were signed “from nature and on stone,” indicating that they were taken directly from on-site sketches. However, lithography was a commercial operation, and because she was adept at every aspect of her trade, was assigned varying roles.

Sometimes she originated the drawing or painting and other lithographers transferred it onto stone. At other times she lithographed or adapted the work of other artists and printmakers. In those cases the original artist’s name was usually indicated on the print, and she was listed as F.F. Palmer, lith.

Lithography was often a collaborative effort, and Palmer sometimes provided backgrounds and landscapes to which other artists at the company added the figures. Currier’s partner, James Ives, seems to have played a role in the conception or lithographing of some of her later prints; his name appears on them along with hers.

From 1866 on, the firm of Currier and Ives occupied three floors in a building at 33 Spruce Street in New York City. Artists, stone grinders and lithographers worked on the fourth floor. Artists produced two to three new images every week for 64 years (1834–1895), producing more than a million prints by hand-colored lithography. At least 7,500 lithographs were published during the firm’s 72 years of operation.

The entire fifth floor of the Currier and Ives factory was devoted to brightly hand-coloring the black ink lithographs produced on the third and fourth floors. Talented young immigrant girls (mostly German) with some kind of earlier artistic training each applied a single color to a print, then passed it to the next girl, who added the next color.

Eventually the evolving picture reached a senior colorist who applied the most difficult details and touched up earlier work where necessary. There was always a model print to follow that the original artist or Fanny Palmer had colored to the satisfaction of one of the partners. However, this assembly line process was restricted to producing smaller prints, and in times of heavy demand its output could be significantly increased.

For instance, in rushing to get a Civil War battle scene on the market while the news was still fresh, a back-up force of less-skilled girls were called in to apply preliminary coloring by stenciling washes over broad areas. Details were then added to these washes by the regular girls, who would more carefully paint the prominent figures and add touches of bright color to battle flags, bleeding wounds and muzzle blasts.

Fanny Palmer retired from Currier and Ives in 1868 at the age of 66, but her prints were, and still remain, among the most popular images ever issued by Currier and Ives. During her lifetime they hung on the walls of thousands of homes and businesses. Some have become national icons, embodying the dreams and aspirations of our expanding young nation.

Late Years

An unheralded artist, few 19th century women worked so hard and got so little credit as Fanny Palmer. It is estimated that she drew more than 200 scenes, more than any other regular artist employed by Currier and Ives, but that number could be significantly higher. She did not always sign her work, and then only identified herself as F.F. Palmer. Was her identity purposely hidden because she was a woman?

In her book, American Women Artists: From the Early Indian Times to Present, Charlotte Rubinstein wrote:

Like a Hollywood screen writer or advertising artist today, Palmer operated as part of a big machine – in this case one that presented a glamorized and picturesque view of America, free of sweating immigrants in factories and slums. The upward mobile public identified with the technological progress, and with images on their walls of well-kept homes, happy families, idyllic landscapes and rich still lifes.

Because she was particularly adept at creating striking background tints and rendering evocative and colorful landscapes, Palmer’s work has also appeared on millions of books, calendars and greeting cards, depicting idyllic scenes of American life. Although her work has been widely used, she has been largely ignored by historians.

Currier and Ives expert Ewell L. Newman wrote:

It is likely that during the latter half of the nineteenth century more pictures by Fanny Palmer decorated the homes of ordinary Americans than those of any other artist, dead or alive.

Fanny Palmer never became wealthy, despite her talent and productivity. She died of tuberculosis on August 20, 1876 and was buried in the Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

SOURCES

Fanny Palmer

Frances “Fanny” Palmer

Fanny Flora Bond Palmer

Frances Flora Bond Palmer

Wikipedia: Currier and Ives

Frances Flora Bond (Fanny) Palmer

Very sad and so very true that such women as Fanny Palmer have received so little recognition for her masterful works of art.