Witness to the Burning of Columbia, South Carolina

Emma Leconte was only seventeen years old when she recorded in her diary the systematic burning of Columbia, SC during General Sherman’s Carolinas Campaign. During the war Emma remained in the city with her mother, while her father Joseph LeConte, a former professor at South Carolina College, worked as a chemist in the Confederate States Nitre and Mining Bureau attempting to make gunpowder for the Confederate army.

Emma Leconte was only seventeen years old when she recorded in her diary the systematic burning of Columbia, SC during General Sherman’s Carolinas Campaign. During the war Emma remained in the city with her mother, while her father Joseph LeConte, a former professor at South Carolina College, worked as a chemist in the Confederate States Nitre and Mining Bureau attempting to make gunpowder for the Confederate army.

After completing his famous March to the Sea by capturing Savannah, Georgia in December 1864, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman began planning his invasion of South Carolina. Emma LeConte began writing a diary on December 31, and her first entry leaves no doubt about her feelings:

They are preparing to hurl destruction upon the State they hate most of all, and Sherman the brute avows his intention of converting South Carolina into a wilderness. Not one house, he says, shall be left standing… And yet they may say there is a Providence who fights for those who are struggling for freedom – who are defending their homes, and all that is held dear! Yet these vandals – these fiends incarnate, are allowed to overrun our land!… How we hate them with the whole strength and depth of our souls.

Backstory

In late January 1865, Sherman launched the invasion of South Carolina, moving 10 to 12 miles a day and burning a swath 60 miles wide. He marched his 65,000-man army in multiple directions simultaneously, confusing the scattered Confederate defenders as to his first true objective, which was the state capital of Columbia.

About 1,200 Confederates under General Lafayette McLaws attempted to prevent the right wing of Sherman’s army from crossing the Salkehatchie River. Union soldiers began to build bridges to bypass McLaws on February 2. At the Battle of Rivers’ Bridge on February 3, 1865, two brigades under General Francis Blair waded through the swamp and assaulted McLaws’ flank. McLaws withdrew toward Branchville after stalling Sherman’s advance for only one day

As Sherman’s army marched through the state during the following two weeks, battles were fought at Branchville, Blackville, Orangeburg and Aiken. The news that reached Columbia during that time was disturbing, and often incorrect.

Emma wrote in her diary on Monday, February 13, 1865:

Father brought in some news this morning… Gen. [Wade] Hampton says Sherman will not come to Columbia. At all events we certainly will know in a day or two what he is going to do.

Diary entry Tuesday, February 14

What a panic the whole town is in! I have not been out of the house myself, but father says the intensest excitement prevails on the streets. The Yankees are reported a few miles off on the other side of the river. How strong no one seems to know. It is decided if this be true that we will remain quietly here, father alone leaving…

It is true some think Sherman will burn the town, but we can hardly believe that. Besides these buildings [on the South Carolina College campus], though they are State property, yet the fact that they are used as a hospital will it is thought protect them… But I cannot believe they are coming!

At the Battle of Congaree Creek on February 15, 1865, Union and Confederate forces clashed at a half-mile-long earthwork erected by Southern forces near the bridge over Congaree Creek. One of the Union brigades crossed upstream and turned the Southerners’ right flank, sending them retreating toward Columbia.

At 10 o’clock am on February 17, 1865, when Columbia Mayor Goodwyn surrendered the city, he received assurances that the city would be unharmed except for public government buildings. The Yankee advance then marched into the city of 14,000 women, children and old men as Sherman and the rest of his occupying force followed. Union forces were overwhelmed by throngs of liberated Federal prisoners and emancipated African Americans.

Over the following hours and days, Emma LeConte recorded the “horror, misery and agony” that accompanied the occupation. On Friday, February 17, 1865 Emma writes:

One o’clock p.m. Well, they are here. I was sitting in the back parlor when I heard the shouting of the troops… In a little while a guard arrived to protect the hospital. They have already fixed a shelter of boards against the wall near the gate – sentinels are stationed and they are cooking their dinner. The wind is very high today and blows their hats around. This is the first sight we have had of these fiends except as prisoners. The sight does not stir up very pleasant feelings in our hearts. We cannot look at them with anything but horror and hatred – loathing and disgust.

Later. Gen. Sherman has assured the Mayor, that he and all the citizens may sleep securely and quietly tonight… Private property shall be carefully respected. Some public buildings have to be destroyed, but he will wait until tomorrow when the wind shall have entirely subsided…

Saturday, February 18

This diary entry tells about the events of the previous night:

What a night of horror, misery and agony!… Until dinner-time we saw little of the Yankees, except the guard about the Campus, and the officers and men galloping up and down the street. It is true, as I have since learned that as soon as the bulk of the army entered the work of pillage began. But we are so far off and so secluded from the rest of town that we were happily ignorant of it all…

We could hear their shouts as they surged down Main Street and through the State house, but were too far off to see much of the tumult, nor did we dream what a scene of pillage and terror was being enacted. From three o’clock till seven their army was passing down the street by the Campus, to encamp back of us in the woods….

Night drew on. Of course we did not expect to sleep, but we looked forward to a tolerably tranquil night… At about seven o’clock I was standing on the back piazza in the third story. Before me the whole southern horizon was lit up by camp-fires which dotted the woods. On one side the sky was illuminated by the burning of Gen. Hampton’s residence a few miles off in the country, on the other side by some blazing buildings near the river. I had scarcely gone down stairs again when Henry [a slave] told me there was a fire on Main Street. Sumter Street was brightly lighted by a burning house so near our piazza that we could feel the heat.

By the red glare we could watch the wretches walking – generally staggering – back and forth from the camp to the town – shouting – hurrahing – cursing South Carolina – swearing – blashpheming – singing ribald songs and using obscene language that we were forced to go indoors.

Ample supplies of liquor were found in the city, and many of the Yankees got drunk before starting the rampage. Vengeful attitudes fueled by alcohol culminated in the looting and burning of the city – an act described by a Union war correspondent as “the most monstrous barbarity of the barbarous march.” Union General Henry Slocum observed: “A drunken soldier with a musket in one hand and a match in the other is not a pleasant visitor to have about the house on a dark, windy night.”

February 18, continued:

The fire on Main Street was now raging, and we anxiously watched its progress from the upper front windows. In a little while however the flames broke forth in every direction. The drunken devils roamed about setting fire to every house the flames seemed likely to spare. They were fully equipped for the noble work they had in hand. Each soldier was furnished with combustibles compactly put up.

They would enter houses and in the presence of helpless women and children, pour turpentine on the beds and set them on fire. Guards were rarely of any assistance – most generally they assisted in the pillaging and firing. The wretched people rushing from their burning homes were not allowed to keep even the few necessaries they gathered up in their flight – even blankets and food were taken from them and destroyed…

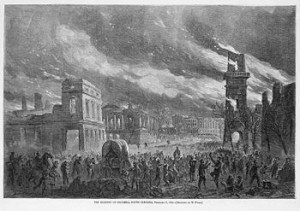

Image: The Burning of Columbia, South Carolina (1865) by William Waud

As fires began in the city, high winds spread the flames across a wide area, and the city’s fire companies found it difficult to operate amongst the invading Union army. The firemen attempted to stop the flames but their hoses were cut and their lives threatened. That night all of the business district and much of the residential area of the city was burned.

February 18, continued:

The wind blew a fearful gale, wafting the flames from house to house with frightful rapidity. By midnight the whole town (except the outskirts) was wrapped in one huge blaze. Still the flames had not approached sufficiently near us to threaten our immediate safety, and for some reason not a single Yankee soldier had entered our house. And now the fire instead of approaching us seemed to recede – Henry said the danger was over and, sick of the dreadful scene, worn out with fatigue and excitement, we went downstairs to our room [in the cellar] and tried to rest…

Founded in 1801, South Carolina College was closed in 1862 and its facilities were leased to the Confederate government for use as a hospital. The campus ‘Horseshoe’ contains 10 of the 11 original pre-1860s campus buildings. The South Caroliniana Library’s holdings now include the surrender note sent to General Sherman by the Columbia mayor and the original diaries of Mary Boykin Chestnut.

February 18, continued:

The College buildings caught all along that [illegible] and had the incendiary work continued one half hour longer than it did they must have gone. All the physicians and nurses were on the roof trying to save the buildings, and the poor wounded inmates left to themselves, such as could, crawled out while those who could not move waited to be burned to death…

I suppose we owe our final escape to the presence of the Yankee wounded in the hospital. When all seemed in vain, Dr. Thomson went to an officer and asked if he would see his own soldiers burnt alive. He said he would save the hospital, and he and his men came to Dr. T’s assistance. Then too about this time even the Yankees seemed to have grown weary of their horrible work – the signal for the cessation of the fire – a blast on the bugle – was given, and in fifteen minutes the flames ceased to spread…

Some soldiers claimed the fires were accidental, others stated they were a deliberate act of vengeance, and others said the fires were set by retreating Confederate soldiers who lit bales of cotton on their way out of town. General Sherman later wrote: “Though I never ordered it and never wished it, I have never shed any tears over the event, because I believe that it hastened what we all fought for, the end of the War.”

February 18, later in the day Emma wrote:

I do not know how the others felt after the strain of the fearful excitement , but I seemed to sink into a dull apathy. We none seemed to have the energy to talk. After awhile breakfast came – a sort of mockery, for no one could eat. After taking a cup of coffee and bathing my face, begrimed with smoke, I felt better and the memory of the night seemed like a frightful dream. I have scarcely slept for three nights, yet my eyes are not heavy….

When will these Yankees go that we may breathe freely again! The past three days are more like three weeks. And yet when they are gone we may be worse off with the whole country laid waste and the railroads out in every direction. Starvation seems to stare us in the face. Our two families have between them a few bushels of corn and a little musty flour. We have no meat, but the Negroes give us a little bacon every day.

Some Yankee soldiers had eventually helped fight the fires, but it was too late. More than two-thirds of the city was destroyed. Already choked with refugees from the path of Sherman’s army, Columbia’s situation became even more desperate when Sherman’s army destroyed the remaining public buildings before marching out of Columbia on February 20, 1865.

Diary entry, Monday, February 20:

Mrs. Bell tells us that Sherman turned loose upon us a brigade that he had never allowed to enter any other city on account of their desperate and villainous character. And yet they talk now of being ashamed of what followed, and try to lay it on the whiskey they found! Shortly after breakfast – O joyful sight – the two corps encamped behind the Campus back of us marched by with all their immense wagon trains on their way from Columbia. They tell us all will be gone by tomorrow evening.

Emma Leconte wrote less and less in the ensuing months and ended her diary as the provisional Governor arrived to oversee Reconstruction in South Carolina. In her last entry on August 6, 1865, she states:

As to the condition of the country and our unhappy state as a people, it would seem better not to think of that, still less to write of it. It makes me miserable and intensifies the wicked feelings I have too much anyway.

After the war Joseph LeConte continued to teach but found Reconstruction politics intolerable. In September 1869, he moved to Berkeley, California to join the faculty of the newly established University of California. He was appointed the first professor of geology, natural history and botany at the University, a post which he held until his death on July 6, 1901.

Emma Leconte later married Farish Carter Furman, the grandson of Richard Furman of Charleston, South Carolina, a prominent minister who helped establish Furman University. Farish Furman became a farmer near Milledgeville and developed a highly successful fertilizer for growing cotton.

Emma LeConte Furman died on March 2, 1932.

Her diary was published as The Day the World Ended: The Diary of Emma LeConte in 1957.

SOURCES

Docsouth: Emma LeConte Diary

Atrueconfederate.com: Emma LeConte

History.com: Union Troops Sack Columbia, South Carolina