Civil War Nurse from Massachusetts

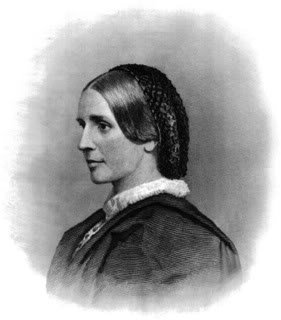

When the Civil War began, Emily Parsons (1824-1880) had a strong desire to enlist in the army as a nurse, despite being partially disabled. Her father was reluctant but finally agreed, and at the age of 37 Miss Parsons enrolled in nursing school at Massachusetts General Hospital in preparation for caring for sick and wounded Union soldiers.

When the Civil War began, Emily Parsons (1824-1880) had a strong desire to enlist in the army as a nurse, despite being partially disabled. Her father was reluctant but finally agreed, and at the age of 37 Miss Parsons enrolled in nursing school at Massachusetts General Hospital in preparation for caring for sick and wounded Union soldiers.

Emily Parsons was born on March 8, 1824 in Taunton, Massachusetts, the daughter of Professor Theophilus Parsons of the Harvard Law School. During childhood, an accident left her blind in one eye and scarlet fever left her partially deaf. Due to an ankle injury she suffered as a young woman, she was unable to stand for prolonged periods of time.

In spite of her physical disabilities – impaired vision, some deafness from scarlet fever and lameness – Miss Parsons entered the nursing school at Massachusetts General Hospital. After eighteen months of training, she was placed in charge of a ward attending fifty wounded soldiers at Fort Schuyler Military Hospital on Long Island in October 1862. For two months, she performed the duties of hospital nurse, but her health deteriorated further.

After a rest, Miss Parsons wrote to Dorothea Dix, superintendent of Union nurses, offering her services wherever they might be needed. At the same time, she became friends with Jessie Benton Fremont, who recommended Parsons to the Western Sanitary Commission at St. Louis, and she was immediately telegraphed to come at once to St. Louis.

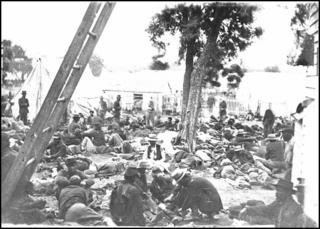

Every available building in St. Louis was converted into a hospital, and the sick and wounded were brought from Vicksburg, Arkansas Post and Helena up the river to be cared for at St. Louis and other military posts. At Memphis and Mound City (near Cairo), at Quincy, Illinois, and the cities on the Ohio River, the hospitals were in an equally crowded condition.

Lawson Hospital

In January, 1863, Miss Parsons went to St. Louis, and was assigned by James E. Yeatman, president of the Western Sanitary Commission, to the Lawson Hospital. A few weeks later, she was placed as head nurse on the hospital steamer City of Alton during the Vicksburg campaign. Emily wrote home:

Darling Mother, I have received your last letter, and glad enough was I to get it: it was delicious; you would write twice a week, if you knew what a longing I had for home news. I want to know everything about everybody. And now my news; I am going to Dixie!

A large supply of sanitary stores were entrusted to Miss Parsons’ care, and the steamer proceeded down the Mississippi River. Working on a hospital ship afforded opportunities for sightseeing and preparing for the wounded who would soon be placed in her care. She was greatly excited and viewed the opportunity as initiation into the army:

I am understanding what it is to be in the army. I never before was among people who took it so seriously, because I never was where the war was around us, nor ever before was going into the midst of it.

At Vicksburg, Mississippi the ship was loaded with four hundred invalid soldiers sick with fever, many of them past recovery, and returned as far as Memphis. On this trip, the strength and endurance of Miss Parsons were tried to the utmost in caring for the helpless and suffering men, several of whom died on the passage up the river. During this period, she contracted malaria.

At Memphis, after transferring the sick to the hospitals, an order was received from General Ulysses S. Grant to load the boat with troops and return immediately to Vicksburg, and Miss Parsons and the other female nurses were returned to St. Louis.

Benton Barracks Hospital

For a few weeks after her return, Emily suffered from an attack of malaria, and on her recovery she was assigned to duty as superintendent of female nurses at the Benton Barracks Hospital, the largest of all the hospitals in St. Louis, built out of the amphitheatre and other buildings at the fair grounds of the St. Louis Agricultural Society.

In this large hospital, there were often two thousand patients, and besides the male nurses detailed from the army, the corps of female nurses consisted of one to each ward, whose duty it was to attend to the special diet of the weaker patients, to see that the wards were kept in order, the beds properly made, the dressing of wounds properly done, to minister to the wants of the patients, and to give them words of good cheer, both by reading and conversation – softening the rougher treatment and manners of the male nurses.

The monotonous army diet of hard bread, salted meat, and coffee without milk needed to be supplemented with fruits, vegetables and dairy products; and inexperienced soldiers needed to learn about proper drainage in the camps and how to set up tents for maximum ventilation. Miss Parsons and others took it upon themselves to give proper attention to the dietary needs and hygiene of the soldiers.

In this important and useful service, the women nurses needed someone of superior knowledge, judgment and experience to supervise their work, instruct them in their duties, secure obedience to every necessary regulation, and good order in the general administration of this important branch of hospital service.

Miss Parsons performed these duties for many months. The work was reduced to a perfect system, and the nurses became a sisterhood, performing a great and loving service to the maimed and suffering. Under Miss Parsons, the Benton Barracks Hospital became famous for its excellence, and for the rapid recovery of its patients. It was not often that the army surgeons gave so fair a trial to female nursing in the hospitals. Too often they allowed their prejudices against female nurses to interfere.

After serving six months in this capacity, recurrent malarial fever sent Miss Parsons back home to Massachusetts. After a short rest, she returned to St. Louis and resumed her position at Benton Barracks. She continued to work there until August 1864, when ill health sent her home again.

By the time she recovered, the war was over, and she devoted herself at home to working for the freedmen and refugees. She collected clothing and garden seeds for them, many boxes of which she shipped to the Western Sanitary Commission at St. Louis to be distributed in the Mississippi Valley, where they were greatly needed.

In the spring of 1865, she took a great interest in the Sanitary Fair held at Chicago, collected many valuable gifts for it, and was sent for by the Committee of Arrangements to go out as one of the managers of the department furnished by the New Jerusalem Church – the different churches having separate departments in the Fair.

Cambridge Hospital for Women and Children

When the war finally ended, Emily Parsons returned home to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where, she addressed the town’s lack of adequate health care for its citizens. She raised money to establish a small charity hospital for women and children, which she opened in 1867 in Cambridgeport, serving as matron and nurse. After a year, the hospital was forced to move.

In 1869 Parsons reopened as the Cambridge Hospital for Women and Children, operating from a rented house. However, the hospital had to close 12 months later when the owner of the house reclaimed his property. Though she persuaded some prominent Cambridge citizens to incorporate the institution, the funds could not sustain the hospital’s work. Parsons closed it once again in 1872. Through her remaining years, she continued to work toward realizing her dream.

Emily Elizabeth Parsons died of a stroke on May 19, 1880. Later that year, her father published her correspondence entitled Memoir of Emily Elizabeth Parsons, detailing her experiences as a Civil War nurse.

Mount Auburn Hospital

The fundraising efforts Miss Parsons had begun continued in her memory, ultimately producing sufficient funds to purchase a nine-acre plot overlooking the Charles River near Gerry’s Landing in 1883. The building of Mount Auburn Hospital began; the first structure completed in 1886 was named the Parsons Building in Emily’s honor. Emily Parsons – described as indomitable, heroic and warm-hearted – continues to inspire those who care about Mount Auburn Hospital.