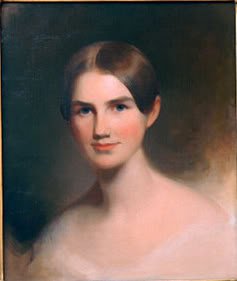

Wife of General William Tecumseh Sherman

Ellen Ewing was a beautiful young woman who played the harp and the piano. After their marriage, the Shermans moved frequently and suffered many long separations as they followed the fortunes of William’s military and business careers. Then the Civil War completely disrupted their lives.

Ellen Ewing was a beautiful young woman who played the harp and the piano. After their marriage, the Shermans moved frequently and suffered many long separations as they followed the fortunes of William’s military and business careers. Then the Civil War completely disrupted their lives.

Eleanor “Ellen” Boyle Ewing, the eldest daughter of Thomas Ewing and Maria Wills Boyle Ewing, was born October 4, 1824, and grew up in Lancaster, Ohio. Thomas Ewing’s close friend Charles R. Sherman, a judge of the Supreme Court of Ohio, died suddenly in 1829, leaving his widow with a family of young children.

Thomas Ewing adopted William Tecumseh Sherman. Over the years, as Ellen and William grew up in the same home, they fell in love. Her father gave only a half-hearted approval of the relationship. He did not want his Ellen to live the nomadic life of an army wife.

Still, Ellen married William on May 1, 1850 at Blair House in Washington DC, where her father was a member of President Zachary Taylor’s Cabinet. Her wedding was attended by the President and his entire Cabinet, as well as Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, whose gift, a silver filigree bouquet-holder, was carried by the bride.

Ellen and William frequently moved as he was stationed in various places – New Orleans, St. Louis, then San Francisco, where William was offered a job establishing a banking business. They left their daughter Minnie with Ellen’s parents in Lancaster when they moved to San Francisco, and took their second child, Mary Elizabeth, age one, with them.

In 1853, they traveled to New York from Ohio, then by boat to San Francisco. It was a very difficult trip. When they reached San Juan del Norte at the mouth of the Nicaragua River, they transferred to another boat with no cabins where they had to sleep on the floor. They went ashore at Virgin Bay and began a 12-mile overland trip by mule. From San Juan del Sur, they took another steamer to California, arriving on October 15, 1853.

Ellen did not like San Francisco with its tramps, fleas and flies. She missed Minnie incredibly and yearned for her home in Lancaster. In June of 1854, Ellen had her third child, William Ewing Sherman. The following year, Ellen returned to Lancaster to bring Minnie home, but she was so attached to her grandparents that Ellen and William decided the child could stay longer with them. On October 12, 1856, Ellen’s fourth child, Thomas Ewing Sherman, was born in San Francisco.

In 1857, because of business troubles in San Francisco, the family returned to Lancaster. William went to New York, then had to return to San Francisco on business. Ellen was devastated. After the bank had failed, William returned to Lancaster, then moved to Leavenworth, Kansas, to practice law. He was admitted to the bar without exam “on the grounds of his general intelligence.”

They returned again to Lancaster where their fifth child was born, Eleanor Maria Sherman. In 1859, William accepted a position as a superintendent of a new military institute in Alexandria, Louisana. In October of 1859, William left for Louisiana. In their first ten years of marriage, they only spent four of them together because of William’s travels.

In mid-1860, just as Ellen and the children were preparing to join William in Louisiana in the new home he had built there, talk of civil war renewed. It was no longer safe for her to travel there. So William returned to Lancaster, resigning his position.

Instead, the family moved to St. Louis where William accepted the position as the superintendent of a street railway there. Several months later, the impending Civil War made it unsafe for the family to stay in St. Louis. William was appointed Colonel of the 13th Regular Infantry and went to Washington.

Though his brother John Sherman was a leader in the party that had elected Abraham Lincoln, William Sherman was very conservative on the slavery question, and his distress at what he thought an unnecessary rupture between the states was extreme. Yet his devotion to the national constitution was unbounded, and he offered his services to the Union as soon as volunteers for the three years’ enlistments were called out.

Ellen and the children returned to Lancaster. They would be separated for another year. On July 5, 1861, daughter Rachel was born. The Shermans’ two oldest children, Minnie and Willy, attended Notre Dame and St. Mary’s in South Bend, Indiana during the war years.

In August 1863, after the Sherman children returned home to Ohio, Ellen took them to visit General Sherman’s encampment on the Big Black River, below Vicksburg, Mississippi during a respite in the fighting. They spent six weeks at the camp.

In late September, as the family boarded the steamboat Atlantic to begin their journey back up the Mississippi River and home to Ohio, William noticed that Willy did not look well. The boy was very quiet and his cheeks were flushed. Surgeon E. O. F. Roler of the 55th Illinois was consulted, and he sadly diagnosed young Willy as having yellow fever.

Image: General William Tecumseh Sherman and his son Willy

Image: General William Tecumseh Sherman and his son Willy

During the trip to Memphis, Willy suffered from high fever, diarrhea and other symptoms associated with yellow fever. Arriving in Memphis, the semiconscious boy was carried by ambulance to the Gayoso Hotel and was seen by the best of physicians. The situation was grim and a Catholic chaplain was summoned to administer the last rites. As Willy floated in and out of consciousness, he realized that he was dying.

Willy told the priest that he was quite willing to die if it was God’s will, but that he did not want to leave his father and mother. With this revelation, Ellen and William Sherman began to weep. Willy reached out and caressed their faces, then closed his eyes and slipped away. He died at five p.m. on October 3, 1863. He was nine years old.

On October 6th, after placing his family on the steamer to return to Ohio, Sherman found himself alone at the Gayoso Hotel, preparing to return to Vicksburg and the continuation of the war. From the hotel, he wrote his wife a letter of total despair:

I have got up early this morning to steal a short period in which to write you, but I can hardly trust myself. Sleeping, waking, everywhere I see poor little Willy. His face and form are so deeply imprinted on my memory as were deep seated the hopes I had in his future. Why, oh why, should this child be taken from us, leaving us full of trembling and reproaches?

Though I know we did all human beings could do to arrest the ebbing tide of life, still I will always deplore my want of judgement in taking my family to so fatal a climate at so critical a period of the year… To it must be traced the loss of that child on whose future I had based all the ambition I ever had.

Sherman never ceased blaming himself for the death of his son. He went insane with grief. Historians now consider the fact that Sherman’s madness, the burning and killing throughout Mississippi, continuing with the March to the Sea, was the result of his insurmountable loss.

In January 1864, four months after Willy’s death, another son, Charley, was born to the Shermans. Ellen’s grief over Willy’s death was intensified by the fact that he had been away from her during the school year. Ellen decided to move to South Bend, taking her new baby with her, so she could be near her other children while they attended the schools there.

When Ellen and the children returned to South Bend for the school year in September of 1864, she got a rose bush from the Notre Dame grounds and a box of pebbles, which she had the children gather from the river bank at St. Mary’s, where Willy often played. She planned to put them on his grave in Lancaster.

Charley, Ellen’s healthy baby boy, had contracted a cold in Lancaster. His condition worsened after they arrived in South Bend. On December 4, 1864, a year and two months after Willy’s death, ten-month-old Charley died in Ellen’s arms. The General was on the march, engaged in hazardous maneuvers through enemy country when the little boy he never saw died.

Sister Angela asked Ellen to be allowed to take the body to Minnie’s school. St. Mary’s Academy. There the St. Mary’s children kept constant watch beside the casket until Wednesday afternoon when Father Sorin performed the beautiful and touching rites of infant burial in the Church of Sacred Heart at Notre Dame.

Image: General Sherman Monument

Image: General Sherman Monument

Washington, DC

General Sherman retired from the army on November 1, 1883, and three years later, he and Ellen settled in New York City. He wrote his memoirs, The Memoirs of William T. Sherman, that consisted of a two-volume set, published in 1875.

Eleanor Ewing Sherman died in New York City on November 28, 1888, survived by her husband and six of their children. She is buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri.

Obituary in the New York Times:

Eleanor Boyle Ewing, the wife of Gen. W. T. Sherman, died yesterday morning at 9:30 o’olock at the family residence, 75 West Seventy-first street. Though Mrs. Sherman has been more or less of an invalid for the past five years, suffering greatly from an affection of the heart, her death came as a very sudden blow to her family.

General Sherman mourned Ellen and Willy for the rest of his life. One year before his own death in February of 1891, he left detailed instructions that he was to be buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, “alongside my faithful wife and idolized soldier boy.”

SOURCES

Eleanor Boyle Ewing

Ellen Ewing Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman

General Sherman’s Family Ties to Notre Dame and St. Mary’s