Union and Confederate Women Who Kept Diaries

The small town of Winchester in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia changed hands between the Confederate Army and Union Army numerous times during the Civil War. The town’s strategic location included a network of seven major roads that radiated out toward other towns and cities; two of the roads were macadamized. This road system made the town a major trade center in the Valley.

The small town of Winchester in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia changed hands between the Confederate Army and Union Army numerous times during the Civil War. The town’s strategic location included a network of seven major roads that radiated out toward other towns and cities; two of the roads were macadamized. This road system made the town a major trade center in the Valley.

Image: Mary Greenhow Lee, Winchester’s most prolific diarist and dedicated Confederate sympathizer

Another geographic feature would magnify in importance during the war: Winchester was surrounded on all sides by low hills that hid the approach of enemy armies. Occupying forces found it almost impossible to mount a defense, so they usually fled quickly, sparing the town from prolonged sieges.

In 1860 Winchester had a population of 4400, which included almost 700 free blacks and a similar number of slaves. The majority of whites were non-slaveholders. The town itself had multiple shops, taverns and hotels, gaslights and a water system. The majority of civilians in the town were against leaving the Union, but when Virginia seceded, that majority became the minority. Many who supported the Confederacy did so because they had a deeper loyalty to their home state of Virginia.

Some historians say Winchester changed hands – between the Confederate Army and the Union Army – more than seventy times during the war, but it was likely less than 20. Wartime diaries suggest that Winchester was under Confederate authority for 39 percent of the war, occupied by Union armies for 41 percent of the war, and between the lines for 20 percent of the war. As a result of continued frustration in the Shenandoah Valley, each successive Union occupation resulted in harsher measures toward civilians.

First Union Occupation (March 1862)

Knowing that his small army were greatly outnumbered by Union General Nathaniel Banks and his army of 35,000, General Thomas Jonathan Stonewall Jackson and his 3500 men reluctantly marched south on the night of March 11, 1862, leaving the town to Federal occupation. The mood of Winchester’s Confederate civilians soured as uncertainty loomed, while local Unionists and African Americans eagerly awaited the arrival of the Union army.

During his stay in Winchester, General Banks attempted to placate the town’s civilians. U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton expressed a sentiment that many Union soldiers serving in the Valley would share – after visiting Winchester in the spring of 1862 he proclaimed, “the men are all in the army, and the women are the devil.” That remark led to the women who kept diaries being called the Devil Diarists of Winchester.

Unionist Julia Chase

While it is difficult to determine precisely how many of Winchester’s population supported the Union during the Civil War, they certainly existed. Union sympathizer Julia Chase kept a diary of activity in Winchester from July 1861 until September 21, 1864, and constantly feared for her family’s safety. Her diary is the only first hand account of a Unionist citizen living in Winchester during the Civil War.

Although tensions between Unionist and Confederate civilians were fairly amicable in the beginning of the war, when General Stonewall Jackson began arresting prominent Union sympathizers in the fall of 1861 and the winter of 1862, tensions intensified. Julia Chase’s diary entries for March 7-9 demonstrate the anxiety experienced by the civilians:

Our town all in excitement this afternoon. People running, soldiers going in all directions.

A fire broke out last night and is said to have been done by incendiary. Heard all the cars at the depot were filled with shavings the object we can well guess. Good many wagons were burnt up yesterday, fearing they might eventually fall into the hands of the Union troops.

Oh the Virginians, how bravely they talk when their Army is near, but how different when there is any sign of the U.S. troops making their appearance. The women seem terribly alarmed at the thought of the Yankees coming here, as if they were all monsters in human form.

Great many Union people have been put in the guard house. We are expecting father will be arrested as we learn the secessionists have 150 names down of Union people.

March 11, 1862:

Fears realized. Father has been taken to the Guard House, and there about 2-1/2 hours, then hurried off to Strasburg… Oh how indignant I felt towards the whole town, to take an old man lying sick on the sofa is outrageous. The older men had the privilege of riding to Strasburg by paying their fare. The rest had to walk.

Confederate Mary Greenhow Lee

Born in Richmond, Virginia, Mary Greenhow Lee was the daughter of Robert Greenhow – Virginia assemblyman, mayor of Richmond and successful businessman. In addition to her family’s wealth, Mary grew up in the presence of some of the most important men in city, state and national government. Her brother Robert Greenhow Jr. trained as a doctor, but then joined the U.S. State Department during Andrew Jackson‘s presidency.

Robert introduced Mary to the workings of government in the federal capital, while his wife, the future Confederate spy Rose O’Neal Greenhow took Mary to social events where she flirted with Martin Van Buren‘s son and drank afternoon tea with Dolley Madison. Mary and Rose formed a strong bond, and their bold personalities would make them fierce Southern supporters during the war.

Mary left Richmond in 1843 when she married the Winchester lawyer and distant cousin Hugh Holmes Lee. Although Hugh and Mary had no children, when he died on October 10, 1856, Mary was not left alone. Hugh’s two unmarried sisters and the four children of Hugh’s deceased sister lived with her. Thus, when the Civil War began Lee had been a widow for more than four years and was the head of household of a large family that included five slaves.

While Mary Greenhow Lee contributed all she could to the cause of Confederate independence, she also made a lasting contribution to history. In March 1862, she began to record the events in occupied Winchester. The ultimate of the Devil Diarists, Lee was perhaps the most vehement in her dedication to the Confederate cause. Her diary is probably the most-often quoted primary source for historians studying civilians in occupied Winchester.

Mary Lee wrote on March 11, 1862:

On going out we met Johnnie Baldwin, in a state of intense excitement; he said we were disgraced, that Jackson was evacuating the town without a fight. It was a terrible moment, that although it had been discussed so often it was impossible to be prepared for. I was skeptical enough to doubt it. We sat round the table trying to arrange what we were to do and what emergencies were to be prepared for. I am in such an anxious state that I am afraid to go to bed, lest I should be roused by the sound of the cannon.

The Yankees advanced this evening to within one mile of our lines and are now encamped three miles from town… The idea that by this time tomorrow night we may be in their [Union] hands, is too terrible for my mind to grasp. I still cling to the conviction that it will not be permitted, I do not think I could feel so calm and self reliant… if such a fate was really in store for me. I almost… hope it would kill me, except that I know the rest of the family would be more helpless without me. Oh, it is terrible to be listening for the cannon, now in the dead hours of the night… I am in a lovely little room, and every sound startles me; horsemen are dashing by continually; why do they ride as if the enemy were pursuing them. May the God of battles have mercy on us.

Lee diary entry, March 12, 1862:

All is over and we are prisoners in our own houses! For about an hour, a death-like stillness pervaded the town, and then music and some cheering announced their approach. The Yankees came in on different streets, more quietly than I had anticipated. Our doors and windows are all closed… There is a sentinel pacing up and down our square.

Unionist Julia Chase wrote on March 12, 1862:

Glorious news. The Union Army took possession of Winchester today and the glorious flag is waving over our town.

In the early stages of their encounters with Union invaders, Shenandoah Valley’s Confederate women adopted a strategy of showing their displeasure with the Federal army by simply ignoring Union soldiers. Mary Lee complained that Winchester men were too cordial in their interaction with Union troops. She believed that there was “no necessity for noticing them or speaking to them, at all, unless in a matter of business.”

Mary Greenhow Lee’s Southern patriotism – and her strength of will and intelligence – led her to make good use of what few material resources she owned to become personally involved in the war. She turned her home into a boarding house for Southern officers, while resolutely refusing to open her home to Union officers during their many occupations of Winchester, implying that they were not worthy of her company.

Three major battles were fought within the town’s boundaries: the First, Second and Third Battles of Winchester. The citizens of Winchester were forever changed by this upheaval in their daily lives. The civilians were affected physically, emotionally and mentally during this seemingly never-ending fight for the town. Among those who took part in battles at Winchester were future U.S. presidents William McKinley and Rutherford B. Hayes, who both were officers in the Union IX Corps.

First Battle of Winchester (May 25, 1862)

After skirmishing with General Nathaniel P. Banks’ retreating army at Middletown and Newtown on May 24, Jackson’s division – no longer numerically challenged – continued north on the Valley Pike toward Winchester. General Richard Ewell‘s division converged on Winchester from the southeast. On May 25, Ewell and Jackson attacked from opposite directions. Panic spread through the Federal ranks, and many fled through Winchester in a decisive victory for the Confederates.

President Abraham Lincoln had appointed Julia Chase’s father, Charles Chase, postmaster of Winchester on May 24, 1862, but General Stonewall Jackson was victorious at the First Battle of Winchester the following day. As an official of the Federal government, Charles Chase fled to Maryland for nine months to avoid arrest. Julia remained in Winchester. When she died on March 15, 1906, her obituary noted that she was “a well-known, and highly esteemed lady of Winchester.”

Image: Jackson Entering the City of Winchester

Image: Jackson Entering the City of Winchester

By William D. Washington

Secessionists freely expressed joy as Banks’ forces abandoned Winchester in May 1862, and there were rumors that civilians fired at Union soldiers as they fled, which caused future invaders to be less conciliatory. When Confederate soldiers returned to Winchester in May 1862, women of the town did their best to feed and care for the wounded soldiers.

By 1863, many residents dreaded the continued presence of either army in the town because of the great strain their presence placed on available resources. Residents of Winchester faced extremely volatile situations, as the town changed hands. As large numbers of troops entered Winchester, residents faced problems ranging from sickness to the scarcity of necessities.

The Hated General Milroy

Harsh Union policies reached new heights under General Robert Milroy, who occupied Winchester on New Year’s Day 1863. Under Milroy, civilians were required to take loyalty oaths to obtain travel passes, food and other necessities. Milroy served notice to Winchester’s Rebel women that they were in for a hard time:

Hell is not full enough. There must be more of these Secession women of Winchester to fill it up.

Buildings in and around the town were torn down to provide construction materials for new forts on the surrounding hilltops. The stately home of former U.S. Senator James M. Mason, a Confederate diplomat, was dismantled brick by brick. Milroy’s mistreatment of Winchester citizens was so harsh that some pro-Unionists changed their sympathies.

Milroy would be remembered bitterly in Winchester as the man who began the harsh practice of sending troublesome citizens through the lines. This meant transporting them by wagon about twenty miles south and dropping them by the side of the road, sometimes in foul weather. These hapless citizens were given little time to gather clothing and supplies they would need on the road.

Second Battle of Winchester (June 13-15, 1863)

During the early Gettysburg Campaign, on June 9, 1863, General Robert E. Lee ordered the II Corps, Army of Northern Virginia under General Richard Ewell to clear the lower Shenandoah Valley of Union troops. Union General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck feared that General Milroy’s position was vulnerable, and ordered Milroy to withdraw his 6,900-man garrison from Winchester.

However, Milroy convinced his superiors that with his extensive fortifications he could hold Winchester against any Confederate invasion, for months if necessary. However, as Ewell’s Confederates closed in on him, Milroy was unaware that his pickets were not well placed in the area, nor did he realize that an entire Confederate corps was preparing to attack him.

During the Second Battle of Winchester, Ewell’s columns converged on Winchester’s garrison. After the fighting on the afternoon of June 13 and the capture of West Fort by the Louisiana Brigade on June 14, Milroy abandoned his entrenchments after dark. CSA General Edward Allegheny Johnson’s division conducted a night flanking march and cut off Milroy’s route of retreat before daylight on June 15.

Milroy escaped with his staff, but Southern forces captured more than 2,400 Federals, all of their artillery pieces and 300 supply wagons. This Confederate victory cleared the Valley of Union troops and opened the door for Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania and the greatest military engagement ever fought on American soil, the Battle of Gettysburg.

Mary Greenhow Lee continued to do what she did best – gathering supplies. She had a network of suppliers north of the Potomac River who provided her with a great deal of goods that she kept hidden in anticipation of the Confederate army’s return to Winchester. She used the services of a local Unionist to send letters to Baltimore and New York requesting money to fund her purchases.

Lee was one of the most resourceful supporters of the Confederacy in the Shenandoah Valley. She amassed a storehouse of contraband for Southern soldiers, building a supply of food, socks and shoes, mindless of the danger to her own personal safety. In the winter of 1863 she confided to her diary:

It requires no little management to spend so much money judiciously & to collect such treasonable supplies, without exciting suspicion. If [Union General Robert] Milroy knew my occupation I would be sent to Fort Delaware.

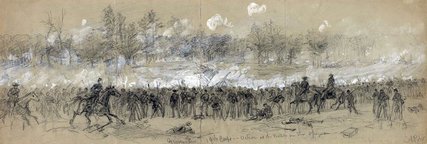

Third Battle of Winchester (September 19, 1864)

General Jubal A. Early renewed his raids on the B&O Railroad at Martinsburg, badly dispersing his four remaining infantry divisions. On September 19, Union General Philip Sheridan advanced toward Winchester along the Berryville Pike, crossing Opequon Creek. The Union advance was delayed long enough for Early to concentrate his forces to meet the main assault, which continued for several hours. Casualties were very heavy.

The Confederate line was gradually driven back toward the town, and by mid-afternoon, the infantry and the cavalry turned the Confederate left flank, and Early ordered a general retreat. Confederate generals Rodes and Goodwin were killed; Fitzhugh Lee, Terry, Johnson and Wharton were wounded. Union general Russell was killed, McIntosh, Upton and Chapman wounded. Because of its size, intensity and result, many historians consider this the most important conflict of the Shenandoah Valley.

Image: Third Battle of Winchester

Image: Third Battle of Winchester

Sketch by artist Alfred R. Waud

Mary Greenhow Lee continued to send intelligence reports to Southern partisan units outside the town, whose operations were severely curtailed by lack of food and fodder. Finally her activities provoked Sheridan into sending her through the lines. She ended up in Baltimore and never returned to Winchester.

In February 1865, General Sheridan exiled Mary Greenhow Lee from Winchester, ordering her to be sent through the lines. She tried to confront Sheridan, but he refused to speak with her. She left Winchester on February 23, 1865, never to return for the remainder of the life. She ultimately settled in Baltimore, Maryland, where she operated three successful boarding houses, and she lived out her final years.

Lee served as an officer of the Baltimore Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and joined a society whose goal was to build schools throughout the South. Mary Greenhow Lee died in Baltimore of kidney failure in 1907. After a memorial service there, her body was taken by train back to Winchester, where she was buried in Hebron Cemetery.

Confederate Cornelia McDonald

Married to Winchester lawyer Angus McDonald III, 23 years her senior, Cornelia Peake McDonald was the mother of nine children and was left to take care of them when her husband decided to join the Confederate Army. On the night of March 11, 1862, as the heavy tramp of marching troops died away in the distance – her husband’s regiment among them – McDonald began her diary of events in war-torn Winchester.

This diary led to her being known as one of the Devil Diarists of Winchester. Throughout her diary she gives concise descriptions of the emotions felt by the citizens of Winchester. As the war continued, McDonald suffered numerous hardships, all the while protecting and caring for her children on her own. Her house was used as headquarters multiple times by Union troops and as a hospital for Confederate troops.

McDonald is noted for tenderly caring for one of her slaves who had run away to the North, only to willingly return after mistreatment with the Union Army. She wrote in her diary:

I never in my heart thought slavery was right, and having in my childhood seen some of the worst instances of its abuse, when surrounded by them and daily witnessing what I considered great injustices to them, I could not think how the men I most honored and admired, my husband among the rest, could constantly justify it, and not only that, but say that it was a blessing to the slave, his master, and his country.

This diary entry illustrates the mental stress McDonald suffered during the war – not only because her home was being occupied by soldiers, but because she feared that her family might not survive the war:

Oh, the sad, sad time, when in the still night I would lie awake, and all the distressing circumstances by which I was surrounded would rise up before me. Our home broken up, my husband and his sons exiles from it, and I and my children only tenants at the will and pleasure of our enemies; and then I would realize the terrible thought that at any time we might be driven out homeless.

In July 1863, Cornelia decided to leave her ravaged farm and move with her children to Lexington, Virginia. In December 1863, Angus McDonald finally joined Cornelia and the children in Lexington, but he was greatly changed. Angus eventually returned to the Confederate army, and that was the last time Cornelia saw him alive. In May 1864, he was captured again and died several months later.

After the war, Cornelia McDonald learned that their homestead in Winchester was unusable. She and her children remained in Lexington, where she raised her children, and became a very happy grandmother.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: The Devil Diarists of Winchester

American National Biograpy: Mary Greenhow Lee

Anticipation and Anxiety: The First Union Occupation, March 1862

Winchester, Virginia: A Town Embattled During America’s Civil War