Union Civilian in the Civil War South

A Unionist circle of women in Atlanta was led by Vermonter Cyrena Stone, who had moved there in 1854. Although the city was under military government, she and her pro-Union cohorts risked their lives to assist the escape of Union prisoners, to protect slaves, and to provide intelligence to General William Tecumseh Sherman‘s advancing army.

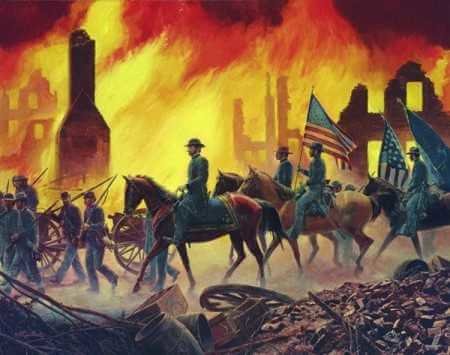

Image: War Is Hell, by Mort Kunstler

General William Tecumseh Sherman destroyed key military, rail and industrial sites with a blaze that gutted much of Atlanta.

Early Years

Cyrena Ann Bailey was born in 1830 in East Berkshire, Vermont, the fifth child of a Congregationalist minister Phinehas Bailey. Less than ten miles from the Canadian border and situated in a lush valley amidst rolling hills, East Berkshire was relatively well-off due to its varied agricultural enterprises. Cyrena spent her childhood and early adult years in that town.

Her mother died in 1839 leaving the nine-year-old Cyrena to carry much of the burden of managing the family while the impoverished Reverend Bailey took various positions in eastern New York state, looking for ways to avoid breaking up his family. He soon found a new wife, who brought more children to the family, and took his entire brood back to East Berkshire. Little else is known about her early years.

Cyrena grew into a handsome woman with dark eyes and dark hair. Though her father was strictly against dances and other social activities, she took part in chaperoned picnics and ritualized visits between families. On one of these excursions she met Amherst Willoughby Stone, four years her senior, the son of a prosperous local farmer.

Amherst studied law with an attorney in St. Albans, Vermont and passed the bar in 1848. Maybe due to an abundance of local attorneys, Stone looked for opportunities in Georgia, where he settled in the town of Fayetteville, twenty-five miles south of Atlanta. He practiced law and became active in local civic affairs there.

Marriage and Family

In August 1850, Cyrena Bailey and Amherst Stone married and began their domestic life together in Fayetteville. Two years later, Cyrena gave birth to a little girl who died from consumption while still a toddler. In 1854, the couple moved to Atlanta where they acquired property and built a large home on the outskirts of the city. The Stones soon became part of the professional elite, helping to found the Atlanta Female Institute and a new Presbyterian church.

By 1860 the Vermont natives owned six slaves or servants, as everyone in the South called them. Because of their backgrounds, owning other human beings must have been difficult for the Stones. Cyrena’s minister father condemned slavery and taught his family to do the same, but slaveholding was fairly common among the Atlanta Unionists and would not have been interpreted as disloyalty to the United States. The Stone’s slaves included a married couple, a single female, and three children.

Unionists in Atlanta

Cyrena Stone became the heart of the Unionist community in Atlanta. A person of courage and resolve, she personified a strict loyalty to the Union exceedingly rare in the Confederate South. Constantly in danger, she recorded her experiences in a diary, shedding light on a rarely seen part of the American Civil War. Her experiences and those of other family members illustrate the complicated character of national versus state loyalty.

The comfortable life that the Stones had built for themselves began to appear threatened as the crisis of disunion intensified in the late 1850s. During the summer of 1860, several Unionists returned to the North to visit family and friends and to contemplate whether remaining in the South seemed wise.

Cyrena Stone habitually spent her summers in Vermont, but friends and family urged her to remain in the safety of Vermont and not return South, but she returned to find Georgia in crisis. The call for a secession convention had worsened the situation. With mounting tensions came increased pressures against Atlanta’s Unionist sympathizers, especially those like Amherst Stone, who had been a frequent speaker at meetings where the issues were debated.

In January 1861, however, as time for the secession convention drew near, about thirty-eight percent of the city’s voters chose candidates who favored a moderate course. Nevertheless, an overwhelmingly pro-secession vote in the state convention took Georgia out of the Union on January 19, 1861.

After the state had become part of the Confederacy, thousands of moderate Georgians chose loyalty to their state rather than to their country. Radical elements now dominated in Atlanta, and they began a sustained effort to suppress dissent of any sort. Vigilance committees rapidly formed to determine each person’s position. One Unionist reported that those “who expressed Union sentiments [were] ordered to leave the state and a good many were whipped or lynched.”

Within a matter of a few weeks, only a few Atlantans held to a strict loyalty to the United States. The circle of Unionists went underground and began to exercise great care in what they said and to whom. Those who had published Unionist arguments now found it nearly impossible to express dissenting views without risking their personal safety. Vocal citizens like Amherst Stone became publicly quiet but met secretly to provide mutual support.

Writing or speaking “anti-Southern” views insured a visit from a vigilance committee – a volunteer group of citizens who assumed authority and meted out justice as they saw fit. Despite all the threats, Cyrena Stone continued to express Unionist sentiments and, using the pseudonym “Holly,” published an essay that could have been interpreted as “anti-Southern.”

Loyalty to neighbors became a moot issue as Atlanta Unionists were systematically excluded from society. Former friends turned into enemies and neighbors acted as spies, watching every move the hated Unionists made. They were shunned at churches. On the streets even children hurled insults and contempt.

Federal prisoners began to arrive in Atlanta in April 1862, soon after the Battle of Shiloh. Many were sick and wounded and received little medical attention. Unionists began helping the prisoners; Cyrena Stone was among the most active. She visited the Union prisoners, sometimes by paying small bribes to guards, or by using their feminine wiles. Cyrena collected money for Union prisoners and then passed it secretly to them during hospital visits. Some used the money to buy food and medicine; others used it to aid in their escapes. These were treasonous acts, fraught with danger.

In the late summer of 1862, martial law was declared in Atlanta and the provost marshal was given the authority to arrest criminals and traitors. In late August 1862, Lee and his men arrested at least eight of the most prominent Unionists – five men and three women – one of which is believed to have been Cyrena.

The killing of a Unionist and the imprisonment of others badly shook Amherst Stone, and he made plans to return to the North. In late 1862 it was still possible for men to leave the Confederacy, even those who were suspected of being Union sympathizers. However, it was virtually impossible to remove entire families; they were used as hostages, ensuring that the men would return.

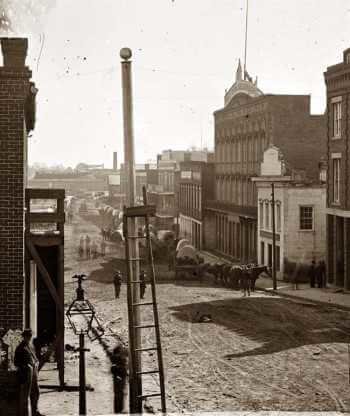

Image: Sherman arrives in Atlanta

Image: Sherman arrives in Atlanta

Army wagon train on Marietta Street

Amherst Stone and others were trying to ship their cotton to the North, and he was able to leave Georgia. Relieved to be safely out of the Confederacy, he went to New York City, where he made preliminary arrangements for a steamer to ship the cotton. He then visited family in Vermont and completed many of his business arrangements by telegraph and mail.

Stone left East Berkshire, Vermont on May 8, 1863, to return to New York. He did not know that his telegrams and letters to New York had been intercepted by the Union provost marshal in Burlington, Vermont, who arrested him in St. Albans. Stone was charged as an agent of the Confederate government.

Stone informed Union Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton of his predicament, and he was released from custody in July 1863. During the next six months, Stone traveled between New York, Washington, and Nashville, trying to put the blockade scheme together.

While Amherst was in the North for nearly two years, Cyrena remained in Atlanta. The surviving fragment of the diary she kept from January to July 1864 shows that she led a life of passionate commitment to the Union. She did not attempt to leave the city as the Union armies approached:

This is my home, & I wish to protect it if possible. There may be no battle here – if not I am safe; if there is one, where is any safety?”

The Union women continued their “disloyal” activities throughout the months leading up to the Battle of Atlanta in July 1864. One of those women told Cyrena that she had been branded a spy and urged her to:

Burn or bury every scrap of writing that would excite suspicion. For you know they say you have been corresponding with the enemy ever since they came to Chattanooga and giving them information – & if we are all arrested, your house will certainly be searched.

During the late winter and early spring of 1864, constant rumors swept through Atlanta concerning the position of the federal armies and the likelihood that a battle might be fought in the city. Confederates believed that General Joseph E. Johnston would repel the Union forces, but as the southern army constantly fell back toward Atlanta, morale began to drop.

“Oh bid them hasten who have promised to come,” Cyrena wrote in her diary in the spring. By late June, the sound of cannon signaled the presence of the federal army was only twenty miles away, and Atlantans were terrified at the prospect of Yankee invaders in their streets.

By mid-July all of Cyrena’s neighbors had retreated to the city or had left the area altogether. A Confederate colonel who had taken refuge in her house advised her to stay at home, that things were more dangerous inside the city. Unknown to him, two free blacks who had been assaulted by Confederate soldiers were hiding in her house a few yards away. At midnight, she recorded in her diary:

Words cannot picture the scenes that surround me – scenes & sounds which my soul will hold in remembrance forever. Terrific cannonading on every side – continual firing of musketry – men screaming to each other – wagons rumbling by on every street or pouring into the yard – for the few remnants offences offers no obstructions now to cavalryman or wagoner, – and from the city comes up wild shouting, as if there is a general melee there.

By the morning of July 22, 1864, Cyrena realized that her home would likely be destroyed during the coming battle. She reluctantly left and took refuge in the home of another Unionist woman with four children, whose husband had also gone north. During the six-week siege of Atlanta, bombs and shells constantly fell upon the city as Union and Confederate forces fought to a stalemate. Twice, cannon shot hit the house where Cyrena was staying.

Fall of Atlanta

With all of his supply lines cut, CSA General John Bell Hood and his troops evacuated Atlanta on the night of September 1. In his Official Report, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman stated:

… About 2 o’clock that night the sounds of heavy explosions were heard in the direction of Atlanta, distant about twenty miles, with a succession of minor explosions and what seemed like the rapid firing of cannon and musketry. These continued about an hour, and again about 4 a.m. occurred another series of similar discharges apparently nearer us, and these sounds could be accounted for on no other hypothesis than of a night attack on Atlanta by General Slocum or the blowing up of the enemy’s magazines.

The next day the Confederates surrendered to Sherman’s officers, and Union troops occupied Atlanta September 3, 1864. Sherman sent a telegram from nearby Lovejoy’s Station to General Henry Slocum, commander of the XX Corps, in Atlanta:

Move all the stores forward from Allatoona and Marietta to Atlanta. Take possession of all good buildings for Government purposes, and see they are not used as quarters. Advise the people to quit now. There can be no trade or commerce now until the war is over.

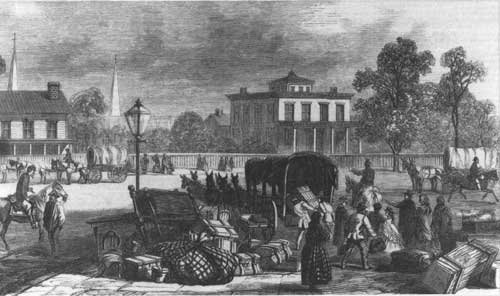

When General Sherman announced his intent to evacuate all Confederate citizens from Atlanta, General Hood protested the order, as did Atlanta Mayor James Calhoun. Sherman replied, “War is cruelty and you cannot refine it.” Between September 11 and 16, 1864 some 446 families – about 1,600 people – left their homes and possessions and headed South.

Image: Civilians leaving Atlanta in compliance with Sherman’s orders

Federal forces sent Cyrena and a large number of Unionist civilians north before they burned the city in early November 1864. Cyrena and Amherst reunited in Nashville in late 1864 and traveled home to Vermont together. Their relationship after the war is not clear, but they spent several years apart.

Meanwhile, Amherst capitalized upon political contacts he had made during his years in the North. Union officials appointed him United States Commissioner in Savannah, Georgia, where he moved in the summer of 1865. During the next eight years he practiced law and held a succession of federal and state political appointments in Georgia.

Even before the war, Cyrena Stone’s health had been fragile; in 1868, still in Vermont, she became quite ill. For a week, she suffered “extreme pain and was partially deranged” until she finally passed on December 18, 1868. She was thirty-eight years old.

In 1873 Amherst Stone left Georgia and accepted an appointment from President Ulysses S. Grant as a federal judge in the Territory of Colorado where he joined his two brothers who were in business together there. Stone died in Leadville, Colorado, in 1900.

SOURCES

The Battles for Atlanta

Wikipedia: Fall of Atlanta (September 1-2, 1864)

Vermont Yankees in King Cotton’s Court: The Case of Cyrena and Amherst Stone – PDF