Female Confederate Spies

Washington, DC was an ideal place for Confederate operatives to gather information against the North. Not only was it adjacent to slave-holding states, it was full of Southern sympathizers, many of whom were members of Congress or held other government positions, which gave them easy access to valuable intelligence. Confederate recruiters only had to find the men and women who were brave enough to act as agents.

Washington, DC was an ideal place for Confederate operatives to gather information against the North. Not only was it adjacent to slave-holding states, it was full of Southern sympathizers, many of whom were members of Congress or held other government positions, which gave them easy access to valuable intelligence. Confederate recruiters only had to find the men and women who were brave enough to act as agents.

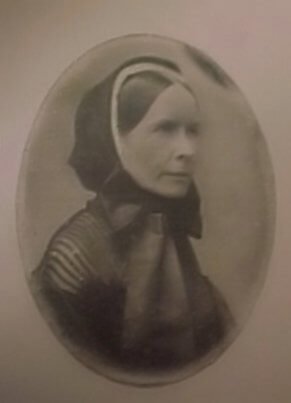

Image: Rose O’Neal Greenhow with her daughter

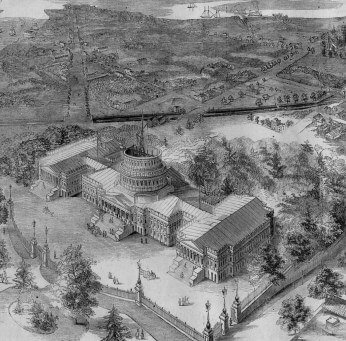

Old Capitol Prison, Washington, DC, 1862

The earliest known spy recruiter was Virginia Governor John Letcher, who immediately set up a spy network in the federal capital. He had been a Congressman in the 1850s and knew the inner workings and social life of the city intimately. Letcher used his knowledge of the city to set up a spy network in the capital in late April 1861, after his state seceded but before it officially joined the Confederacy.

Rose O’Neal Greenhow

Two of Letcher’s most prominent early recruits were Thomas Jordan, a Virginia-born West Point graduate stationed in Washington before the war, and Rose O’Neal Greenhow, a beautiful openly pro-South 44 year-old widow and Washington socialite who was friendly with a number of northern politicians, including several senators and Secretary of State William Seward.

In the spring of 1861, Letcher assigned Thomas Jordan to recruit Greenhow, who accepted the job enthusiastically. Greenhow once wrote to Jordan: “Tell Aunt Sally that I have some old shoes for the children, and I wish her to send one down town to take them, and to let me know whether she has found any charitable person to help her take care of them.” That message actually meant: “I have some important information to send across the river, and wish a messenger immediately. Have you any means of getting reliable information?”

Greenhow passed her coded messages to a courier who then passed them to the next link in the chain of men and women who slipped in and out of taverns, farms and waterfront docks along routes that connected Baltimore and Washington to the Confederacy. The reports were then delivered via the Secret Line, the system used to get letters and intelligence reports across the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers and into the hands of Confederate officers.

In July 1861, Greenhow, one of the most important women spies for the South, sent coded reports to Jordan (now in the Virginia militia) about a planned Federal invasion. One of her couriers, a young woman named Bettie Duvall, dressed as a farm girl in order to pass Union sentinels on the Chain Bridge leaving Washington, then rode at high speed to deliver her message to Confederate officers at Fairfax Courthouse, Virginia. Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard later credited the information received from Greenhow with helping his army win the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861.

I employed every capacity with which God has endowed me, and the result was far more successful than my hopes could have flattered me to expect.

~ Rose O’Neal Greenhow

The National Archives has digitized and made available in the Archival Research Catalog (ARC) one hundred and seventy-five documents that the U.S. Intelligence Service seized from Greenhow’s home in August 1861.

Belle Boyd

Only 17 years old when the Civil War began, by early 1862 Belle Boyd of Martinsburg (now West Virginia) and her activities were well known to the Union Army and the press, who dubbed her La Belle Rebelle. While visiting relatives whose home in Front Royal, Virginia was being used as a Union headquarters, Boyd learned that Union General Nathaniel Banks’ forces had been ordered to march.

She rode fifteen miles to inform Confederate General Stonewall Jackson who was nearby in the Shenandoah Valley. She returned home under cover of darkness. Several weeks later, on May 23, 1862, when she realized Jackson was about to attack Front Royal, she ran onto the battlefield to provide the General with last minute information about the Union troop dispositions. Jackson captured the town and acknowledged her contribution and her bravery in a personal note.

Boyd was arrested several times, but managed to avoid incarceration until July 29, 1862, when she was imprisoned in Old Capitol Prison in Washington, DC, but was released after a month. She was arrested again in July 1863, after which she devised a unique method of communicating with her supporters outside. They shot rubber balls into her cell with a bow and arrow; she then enclosed messages inside the balls and threw them back.

In December 1863 Boyd was released and banished to the South. She sailed for England on May 8, 1864, but was arrested again as a Confederate courier. She finally escaped to Canada with the help of a Union naval officer, Lieutenant Sam Hardinge, and eventually made her way to England where she and Hardinge were married. Boyd later wrote of her wartime activities, “I allowed but one thought to keep possession of my mind – the thought that I was doing all a woman could do for her country’s cause.”

Nancy Hart Douglas

Scout, guide and spy for the Confederacy, Nancy Hart Douglas served first with the Moccasin Rangers, a prosouthern guerilla group in present-day West Virginia. She rode at the head of that column during 1861 and 1862, throughout the central counties of western Virginia. Hart became so famous and such an enigma for Union forces in western Virginia that a large reward was offered for her capture in the summer of 1862.

Shortly thereafter, Nancy and a female friend were captured by Union troops led by Lt. Col. Starr and taken prisoner in Summersville, West Virginia. She was held prisoner in present-day Summersville, West Virginia, in the upstairs portion of a dilapidated house, with soldiers quartered downstairs and a sentry with her at all times. Civil War telegrapher Marion Kerner, an officer who befriended Hart at the Union encampment, later made her story famous in the magazine, Leslie’s Weekly.

One evening, Nancy grabbed the pistol from her naive young guard, leapt out a second-story window into a clump of tall jimson weeds, stole Starr’s horse, and escaped behind Confederate lines. On July 25, 1862, at 4:00 am, Nancy returned to Summersville with 200 Confederate cavalrymen. The Rebel troops came storming up the road, overran the pickets, and entered the town without opposition. Nancy, still riding Starr’s horse, and the Confederate forces captured 8 mules, 12 horses and several prisoners, including Lt. Col. Starr.

Hart also collected intelligence behind Federal lines and carried messages between the Confederate armed forces in western Virginia, traveling alone by night and sleeping during the day. Posing as a farm girl peddling eggs and vegetables to the Yankees, she scouted isolated Federal outposts in the mountains and reported their strength and vulnerability to General Stonewall Jackson.

Olivia Floyd

A most unlikely Confederate spy and messenger, Olivia Floyd was heir to the Rose Hill mansion near Port Tobacco, Maryland and was living there during the Civil War. In the winter of 1864, a group of Confederate soldiers raided St. Alban’s, Vermont and escaped to Canada with only their horses, money and lives. They were then arrested by Canadian authorities and Union officials sought their extradition to be tried as spies.

The lives of these men depended on proving that they were commissioned officers of the Confederate Army acting on official orders. A message started south requesting the commissions of the men. It passed from one Southern sympathizer to the next, from Canada to Maryland, and finally to Miss Floyd, the last person in the chain of communications into Confederate territory.

Miss Floyd concealed the important note in a pair of brass andirons in her parlor which were missed by Union soldiers. One had even propped his foot up on the very same andiron by the fire. After they had left, she put the note in her hair and carried it to the signal station at Popes Creek where it had been sent to Richmond. The result was the soldiers on trial in Canada received copies of their commissions in time to save them.

Local Union troops became suspicious of Miss Floyd, and just after she received this message, soldiers were sent to search her home. Looking about for a place to hide the important note, she suddenly remembered that the pair of brass andirons at her parlor fireplace had hollow brass balls at the top. She placed the document in one of the hollow balls, not long before the Union soldiers arrived.

After searching the house, and finding nothing, the men stopped in the parlor to relax for a short time by the fire, one of them resting his feet on the very andirons that contained the message. After they had gone, Olivia hid the document in her hair and rode to the signal station at Popes Creek, Virginia where the message was sent to Richmond, where authorities forwarded the commissions of the imprisoned Confederates to Canada in time to save their lives.

Laura Ratcliffe

The Frying Pan area of Fairfax County, Virginia was home to dark-haired beauty and Confederate spy and messenger Laura Ratcliffe. Her home was sometimes used as headquarters by CSA Colonel John Singleton Mosby, who was called the Grey Ghost because he eluded capture so many times. On February 7, 1863, a trap was set for Mosby near Laura’s home. A young Union lieutenant could not resist boasting about it to her when he came by to purchase milk:

I know you would give Mosby any information in your possession; but, as you have no horses and the mud is too deep for women folks to walk, you can’t tell him; so the next you hear of your ‘pet’ he will be either dead or our prisoner.

He obviously underestimated Miss Ratcliffe, who walked on foot across muddy fields to reach the home of her cousin George Coleman to ask him to warn Mosby. As luck would have it, she met Mosby along the way and was able to warn him herself. He acknowledged his great debt to her in his memoirs.

Ratcliffe also provided continuing intelligence to the southern troops and served as banker for Mosby’s Rangers by hiding money and supplies under a large rock near her home that came to be known as Mosby’s Rock. Although it was obvious that her home was the center of Confederate activity, Ratcliffe was never arrested or formally charged.

Among Ratcliffe’s many admirers was the famous General (James Ewell Brown) J.E.B. Stuart who presented her with a gold-embossed brown leather album in which he wrote four poems to her. The album was signed by Stuart and many other soldiers who fought with him including Mosby. She kept the album and a gold watch chain, also given to her by Stuart, among her possessions at her home, Merrybrook, where they were discovered after her death in 1923.

Confederate Espionage

Spies were very active on both sides during the Civil War. Union spies were more numerous, but southern spies were often more interesting, if not more effective. There are doubtless many Southern women who followed their convictions and served as spies whose stories will never be told because they were not recorded. Fearing detection, details of their activities were never committed to paper; countless incidents involved only three or four people, who never revealed their secrets.

And we will never know the complete story of Confederate espionage. By March 1865 the Confederate government saw the end coming and quietly began packing its archives and removing them from Richmond. On April 1, 1865, General Robert E. Lee informed Confederate President Jefferson Davis that he could not hold out much longer, and would have to evacuate the Richmond defenses, which would turn Richmond into an open city for Union troops and officials.

The Confederacy’s Signal Corps was devoted primarily to communications and intercepts, but it also included a covert agency called the Confederate Secret Service Bureau, which ran espionage and counter-espionage operations in the North including two networks in Washington.

Thus, on April 2, 1865, one of the last acts of Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin before evacuating Richmond was to burn the papers related to Confederate espionage activities, for in addition to his other responsibilities, Benjamin was in charge of a number of shadowy projects which were underway in Canada and the Northern United States. Those papers were too sensitive to remain in a government office about to be overrun by Union troops.

Years later Jefferson Davis discouraged attempts to reveal details of Confederate spying. Too many people might be hurt. Nevertheless, a great deal of data is available from a variety of sources. In the Official Records of both armies there are thousands of pages of correspondence, orders of inquiry and arrest, mostly about civilian spies. The stories are said to be at times bizarre, almost unbelievable.

SOURCES

Civil War Trust: Maria “Belle” Boyd

CIA: Intelligence Collection – The South