First State Capital to Fall to the Union Army

Image: View of Nashville from the steps of the Capitol Building, with Union artillery in place

Nashville, Tennessee was an extremely important city during the Civil War. It was in the top 50 of the most populous cities with 17,000 residents. After Fort Donelson fell to Union troops February 16, 1862, Confederate authorities surrendered Nashville to Union forces without firing a shot.

Union Occupation

In February 1862, Confederate leadership surrendered two strategic Tennessee forts. A Union Army and Navy team under General Ulysses S. Grant took Fort Henry on the Tennessee River (February 6), and then captured Fort Donelson (February 16), only twelve miles from Nashville. After the fall of the Forts, Union gunboats advanced up the Cumberland River to Nashville. The city’s significance as a shipping port made it desirable to the Union.

Governor Isham Harris made a speech, recommending that citizens burn their private property; retreating Confederate troops destroyed bridges crossing the Cumberland River so they could not be used by the enemy.

Many civilians chose to leave Nashville. Refugees soon took their place. Unionists and Rebels both flooded in, as did free blacks and escaped slaves. Jobs were plentiful in the depots, warehouses and Union military hospitals, and the city was much safer than the countryside. A secret Confederate underground operated in the city throughout the Union occupation; smuggling arms, medicines and information; helping prisoners escape; and giving information to spies.

On February 23, 1862, the Confederate army surrendered Nashville to Union forces, the first Southern state capital to fall to the enemy. Stunned civilians watched from the banks of the Cumberland River as Union soldiers marched into Nashville, and began setting up camp on the grounds of the State Captiol Building. Union troops suddenly outnumbered the locals.

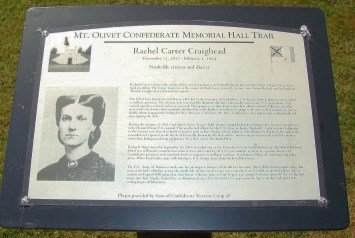

Rachel Carter Craighead

Rachel Carter (1837-1924) had married Nashville lawyer Thomas David Craighead December 4, 1859, and the couple lived at her parents’ affluent home. They had no children. The diaries she kept provide an excellent reflection of life among the city’s upper class during the Civil War. She complains of troops in her church services, saying “I think they might let us worship without them.”

Image: Marker with image of Rachel Carter Craighead

Mt. Olivet Confederate Memorial Hall Trail

Craighead’s diaries include reports of battles, and friends killed or wounded. In 1863 her brother John Carter died from wounds he had received at the Battle of Perryville. Of special interest is her account of General Grant’s stay in her home in 1864. In 1865, Craighead received news of Lee’s surrender to Grant, and a few days later she recorded her shock at hearing of Lincoln’s death.

Andrew Johnson

On March 4, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln appointed U.S. Senator Andrew Johnson Military Governor of Tennessee. During the secession crisis, Johnson had remained in the U.S. Senate even when Tennessee seceded, which made him a hero in the North and a traitor in the eyes of most Southerners. Johnson set up offices in the State Capitol at Nashville, about a block from Rachel Carter Craighead’s home.

During his term as military governor, Johnson used the state as a laboratory for reconstruction. Soon after his arrival in Nashville he decided to make an example of someone, and ordered three high-profile arrests. The man who had helped negotiate Tennessee’s entry into the Confederacy, a judge who had been outspoken in support of secession, and the man who had been in charge of arming Tennessee’s Confederate soldiers were shipped off nearly 800 miles, to a fort in Northern Michigan.

This sparked rumors, which Craighead wrote about in her journal:

Said they were going to arrest everybody who had aided the Rebellion. They had better build a wall around the city and take out the Union men. I think that much easier than any other way.

The Dreaded Oath

City leaders, clergy and businessmen were told that their right to work in the city hinged on signing an Oath of Allegiance to the Union. Reverend Robert Howell, the pastor of First Baptist Church, responded in a letter to Johnson, even though he knew he would probably be arrested:

There is nothing known to me in the Federal Constitution, nor in the constitution of this state, which requires me to repeat that oath. I most respectfully decline it and take the consequences.

Many prominent people served time in the local penitentiary for their refusal to take the oath, including Craighead’s father, prominent Nashville banker Daniel F. Carter. He was arrested in his bank and sent to the penitentiary for refusing to take the Oath of Allegiance to the Union. Craighead wrote that the keys to the safe were confiscated as he was arrested. “I was so angry to think of those demons taking my dear father in front of their bayonets.”

Craighead’s entry for April 16, 1863, told of a notice in that day’s paper ordering every white person over 18 to take the oath in 10 days or be sent South. Now, instead of prison time for the men of the city, refusal brought the risk of uprooting their families entirely. For lack of any alternative, most signed this oath:

I do solemnly swear that I will support, protect, and defend the Constitution and the government of the United States against all enemies, whether domestic or foreign; and that I will bear true faith, allegiance and loyalty to the same, any laws, ordinances, resolution or convention to the contrary notwithstanding; and further, that I do this with a full determination, pledge and purpose without any mental reservation or evasion whatsoever; and, further, that I will well and faithfully perform all the duties which may be required of me by law. So help me God.

Over the next six weeks, almost eleven times more people swore to the oath than in the entire year prior. From that point on, Washington considered Nashville loyal, and the Union Army made it one of their key supply centers. The Union never lost control of the city.

Rebel Siege?

In November 1864, Confederate General John B. Hood led the Army of Tennessee out of Alabama toward Nashville, in an effort to cut off Union General William Tecumseh Sherman‘s supply line. But conditions were hard: the ground was frozen, rations almost completely gone. Soldiers described the long walk: “Our shoes were worn out and our feet were torn and bleeding… the snow was on the ground and there was no food.”

Rumors of the Confederate Army’s arrival began long before it actually arrived. From the handful of forts in the city, Federal troops kept watch. For several miles to the South, whatever land that had not already been kept treeless for farming had now been cleared to make it harder for attackers to hide.

Hood’s army arrived south of the city on December 2. Since his approximately 30,000 men were not nearly strong enough to assault the Federal fortifications, Hood entrenched and waited, hoping that Union commander, General George H. Thomas, would attack him. Then, after Thomas smashed his army against Confederate fortifications, Hood would counterattack and take Nashville.

The Southerners were smart not to launch a direct attack. Nashville, protected by 55,000 men, was one of the most heavily fortified cities on either side of the war. A string of forts and well-built defensive lines curved around the South side of town, intersecting with the Cumberland River on either end. US Navy gunboats patrolled the river, watching for threats on the shore.

Soon after Hood’s arrival, a major winter storm moved through the area, bringing with it sleet, ice, and snow, halting all military activity. For almost two weeks, both sides waited for the weather to clear. Authorities in Washington, DC and Virginia grew more impatient with each passing day. General Thomas tried to explain that all Nashville roads and bridges were crusted with ice. Even his cavalry could not safely move into position.

Every day, Thomas received angry telegrams. “General Grant expresses much dissatisfaction,” one read, going on to warn that if he waited to move the cavalry, “you will wait till doomsday.” Others made it clear that orders were being written up that would remove him from command. At one point, it looked as if General Ulysses S. Grant might leave his siege of Petersburg, Virginia to take control of Nashville himself.

Image: Map of Nashville during the battle

Image: Map of Nashville during the battle

Confederate line shown in red, Union line in blue

Credit: Mack Linebaugh, WPLN, Google Maps

Battle of Nashville

On December 15, there was finally a break in the weather, and Thomas finally moved forward. The Battle of Nashville had begun. The Union plan called for a diversion on the Confederate right while the main Union assault struck their left. Fierce close-range combat erupted. That afternoon, the Southern line crumbled and retreated as the sun went down.

It was not clear to Thomas if they would fight again the next day, or if the Confederates were marching out of town. Under cover of darkness, Hood moved two miles farther south, and the Southerners built new breastworks and moved heavy cannon onto a pair of hills that served as the Eastern and Western anchors for their positions.

Rebel Retreat

General George Thomas renewed the attack on the morning of December 16. After several hours of fighting, Union soldiers broke through the Confederate fortifications, and Union forces swarmed over the Rebel trenches. The Confederate flank on Shy’s Hill was captured, and with it, all the large guns that were meant to send the Federals packing. The entire Southern line fell like dominos, and its men did not wait for orders to retreat. They just ran.

Hood ordered a hasty retreat south, and only a skillful rearguard action allowed his army to escape. The once powerful Army of Tennessee was nearly destroyed. The Union victory at Nashville shattered the Army of Tennessee and effectively ended the war in Tennessee.

Many in Hood’s Confederate army were Tennessee natives, and as they ran, some soldiers may have chosen to quietly leave the group and head home. If they had tried that earlier in the war, they would have been executed for desertion. But now their army could not feed or clothe them, and was dumping wagons and destroying ammunition as it went to lighten the load. It was not an army anymore.

Union troops trailed the Confederates for almost ten days. By the time the Southerners re-crossed the Tennessee River, Hood’s army had disintegrated, as men were dying from cold or famine or taking off for shelter in different directions. Although Hood blamed the entire debacle on his subordinates, his career was over. He resigned his command on January 13, 1865, and was not given another field command.

Aftermath

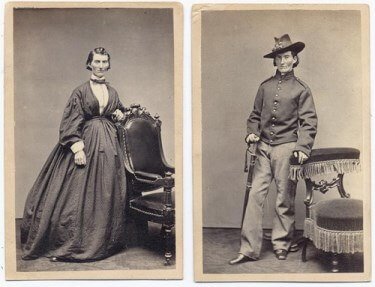

The War left much of Middle Tennessee in ruins, but it also brought enormous change. Many Tennessee women had assumed new roles during the war: running plantations and farms, managing businesses, serving as nurses, and spying on the enemy. Women’s lives would never be quite the same. Nothing before or since would have such an impact on Nashville as did the Civil War.

SOURCES

Civil War Trust: Nashville

Wikipedia: History of Nashville, Tennessee

Civil War Sesquicentennial: Nashville’s Occupation

Union Troops Broke Through the Confederate Line

Nina Cardona: 150 Years Ago In Nashville, The Beginning Of The Civil War’s End

Thank you for your well-written and informative blog post. Recently I discovered that one of my ancestors (great grand father Pvt. James Marion Moates of Eucheeanna, Florida and Co. E 1st Florida Infantry CSA) was captured at Nashville in December 1864. I believe that his unit was on Shy’s hill during the battle. It is amazing how this fact transforms my interest in the details of the local history since moving to Middle Tennessee from academic to personal.

My great grandfather reported years later that he was captured in Nashville and “remained under guard for five months.” I have not succeeded in finding his name among the prisoner registers of Louisville Military prison, Camp Chase, nor Fort Douglas even though several of his compatriots appear in the lists. Were any prisoners held in Nashville in the Spring of 1865 as prison labor and not transported to prison? James Marion was literate and had a beautiful hand. Later in life he was selected as a church clerk, in part perhaps because of this skill. Is here precedent for such a situation?

Thank you, again for your excellent work.

Dr. Sam Matteson

UNT Distinguished Teaching Professor Emertitus (Physics)