Wife of Union General Alexander Hays

Annie Hays suffered the long separations from her husband that all wives of Civil War generals endured. However, letters from the front inspired these women to continue raising children, caring for homes, running farms, and operating businesses. Unfortunately, Annie’s husband never made it home. He was killed at the Battle of the Wilderness on May 6, 1864.

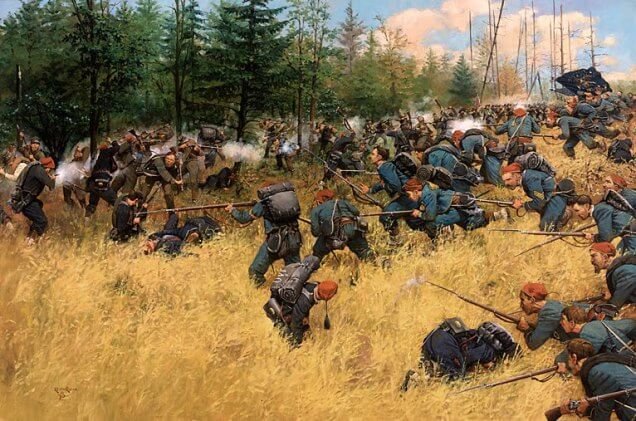

Image: Into the Wilderness by Keith Rocco

Image: Into the Wilderness by Keith Rocco

Annie Adams Farrelly was born March 15, 1826 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Two months earlier, her father, U. S. Representative Patrick Farrelly, died while en route to Washington to attend Congress. In 1835 her mother married John Birch McFadden, a Market Street jeweler in Pittsburgh.

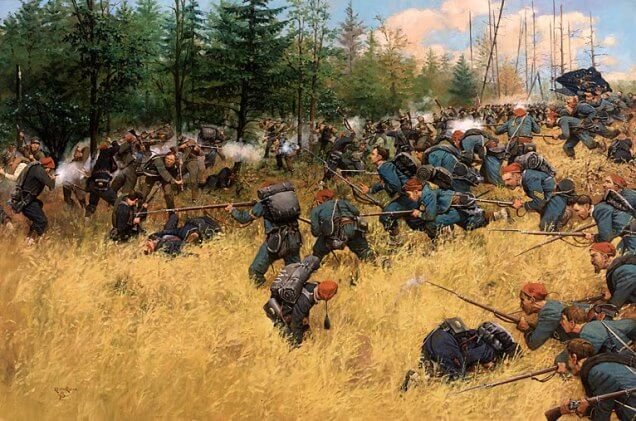

Alexander Hays was born July 8, 1819, in Franklin, Pennsylvania, north of Pittsburgh. He was the son of Agnes (Broadfoot) and Samuel Hays, a member of Congress and a general in the Pennsylvania Militia. Alexander Hays attended Allegheny College until his senior year when he left to enter West Point in 1840. Hays graduated 20th in a class of 25 in 1844. His class included future Civil War generals Alfred Pleasonton and Winfield Scott Hancock, and he became a close friend of Ulysses S. Grant who had graduated the year before.

Commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 8th U.S. Infantry, Hays won distinction in an engagement near Atlixco during the Mexican-American War. In April 1848, he resigned from the army and returned to Pennsylvania, where he went into the iron business, but it failed. He then traveled to California during the Gold Rush, but he returned to western Pennsylvania, engaging in bridge-building for railroads and towns.

Marriage and Family

Annie Adams McFadden married Alexander Hays on February 19, 1846 at the McFadden home. The wedding trip was to Buffalo, New York. From 1854 until 1861, Hays was a civil engineer in Pittsburgh. Of this union there were nine children:

Agnes Milnor Hays

John McFadden Hays died in infancy

Alden Farrelly Hays

Rachel McFadden Hays

Gilbert Adams Hays

Allan Hays died in infancy;

Martha Alden Hays,

Alfred Pearson Hays,

James McFadden Hay

Hays in the Civil War

When the Civil War began in 1861, Alexander Hays re-entered the service as colonel of the 63rd Pennsylvania Volunteers, and then the rank of Captain to date from May 14, 1861. During the Peninsula Campaign, Hays led the regiment for the first time in combat. At Glendale (June 30, 1862), he led his regiment in a bayonet charge into the enemy line to save a battery that was trying to retreat. In his report, division commander General Philip Kearny called Hays maneuver a “heroic action.” A month later, Hays suffered health issues and went on sick leave. The surgeon who examined him reported he was blind in his right eye and his left arm was partially paralyzed.

In early 1863, Hays was promoted to brigadier general and assigned as commander in the XXII Corps in the defenses of Washington, DC. Hays and his men participated in the Second Battle of Bull Run in August 1862. His regiment was spearheading General Kearny’s division in an attack on General Stonewall Jackson, when a Rebel bullet hit Hays’ leg, putting him out of commission for several months. Hays himself later wrote:

A large ball struck the main bone between the ankle and knee, not breaking, but perhaps splintering it, glancing off and breaking the smaller bones. The entrance hole is as large as a half dollar. I assure you, I have a sore shin, but a quarter of an inch variation would have cost me my leg.

Valentine’s Day Letter

From winter quarters at Union Mills, Virginia, Alexander Hays wrote this letter to Annie Adams McFadden Hays dated February 14, 1863, but it is not very romantic.

Dear Wife:

It has this minute struck me that this is St. Valentine’s day and this will be my valentine to the best woman in the world. … I would dance like a fairy if I could have her here for only one week. Since I lost my own special correspondent by consequence of departure for Philadelphia, I am constrained to do my own letter writing, for which I am totally unfitted when so much of the pronoun ‘I’ is required I will tell you, however, what Mr. I did yesterday:Colonel Stagg of the cavalry brought me the information that 45 of his men had been attacked by superior forces of the enemy. I had been very busy all day, in shipping the 151st Pennsylvania and was very tired, but I forgot my troubles when I heard the news. After dinner I started with 100 cavalry and 40 mounted artillery in command of Lieut. Creely, an ambulance and a surgeon. Bull Run [the creek] was high, almost swimming our horses, but with a hope that we might meet the Rebels, all took water with a will, for my part I got two boots full. After seven miles’ ride, we arrived at the scene of action. Several dead horses was all that was left to indicate it. We found one dragoon, very badly wounded, and several others more or less so.

The Rebs had left, and we returned home, without firing a shot. It was after dark, and I for one, was wet, hungry and tired. I slept soundly, but when I awoke this morning, to write to you, I discovered that I had contracted a cold. …

Writing so often, and having received not one word from you, even of your safe arrival at Philadelphia, I cannot he expected to write very long letters.

Love to all the dear ones.

Your husband,

Alex

Hays at Gettysburg

On June 28, 1863 – three days before Gettysburg – Hays was given command of the Third Division, II Corps. Thus, at Gettysburg, not only was Hays new to division-level command, he was completely unfamiliar with two of the brigades in his new division. However, instead of the Old Army distrust of civilian recruits, he loved the volunteers, and they loved him for his brave leadership. Hays, always an emotional fighter, had a special intensity at Gettysburg, explaining:

I was fighting for my native state, and before I went in, thought of those at home I so dearly love. If Gettysburg was lost, all was lost for them, and I only interposed a life that would be otherwise worthless.

At dawn July 2, the three brigades of Hays’ Third Division were assigned to hold Ziegler’s Grove, a strip of trees at the northern end of Cemetery Ridge. As his troops deployed around the grove, the humid calm was rent by gunfire as the Rebel line put up stiff opposition to their arrival.

Image: General Alexander Hays

Image: General Alexander Hays

No image of Annie Hays is available

Fighting at Bliss Farm: Day Two

Shortly after 10 a.m. July 2, General Hays ordered the 39th New York to reinforce the skirmishers in his front. Crossing the fences along Emmitsburg Road, the men fanned out into the fields north of the buildings at Bliss Farm. Watching from Cemetery Ridge, Hays saw the 39th New York was in trouble. Confederate reinforcements at the orchard west of the Bliss barn were threatening the skirmishers. Hays rode out to his men, shouting instructions and encouragement, and the toughness of those men grew as they held their position for several hours despite the gunfire and July heat before they withdrew.

The buildings at the Bliss Farm were the only substantial shelter in the open fields below town, and they were rapidly becoming the focus of the contest that July morning. Located in the broad valley southwest of Gettysburg, the 60-acre farm lay midway between General Robert E. Lee‘s main battle line on Seminary Ridge and Winfield Hancock’s Union II Corps on Cemetery Ridge. The barn was a perfect place for sharpshooters of either army to harass the enemy, making it an important location in the fierce fighting that followed.

At that time, the buildings at Bliss Farm were held by the Union skirmish line, but the Mississippi soldiers of Brigadier General Carnot Posey soon attacked and occupied the structures. When the Mississippi troops inflicted casualties on Hays’ skirmishers, members of the 12th New Jersey Infantry were detailed to re-take the farm. When they reached the farmyard, the New Jersey column halted, delivered a volley into the barn, and surrounded the building, capturing about 50 Mississippi riflemen. But the Southerners continued shooting from the Bliss house 90 yards away.

One of the New Jersey companies charged from the barn and captured the Bliss house, but the Confederates soon drove Hays men out of the buildings. Entering through the large doors facing the Southern lines, Confederate marksmen filled the upper story of the barn. Hays moved his headquarters to the Brian house near Ziegler’s Grove, and he and his staff began to attract the attention of the Confederate riflemen.

At 5 pm, Hays ordered the First Delaware to re-establish the Union skirmish line and occupy the Bliss buildings. With a cheer, the troops shouldered their smoothbore muskets and moved out at double-quick across the 400 yards to the Bliss buildings. Immediately Rebel sharpshooters and batteries on Seminary Ridge opened fire on the charging Federal line.

By this time, an en echelon assault by CSA General James Longstreet‘s Corps was underway and rolling north. The Confederate advance had broken the Union left flank at Devil’s Den, pushed through General Daniel Sickles‘ salient at the Peach Orchard, and unhinged the Yankee line on the Emmitsburg Road. The four New Jersey companies holding the Bliss farm buildings were in a tight spot, and they withdrew to Cemetery Ridge.

By 7 pm, the Federal positions on Cemetery Ridge had changed dramatically. Only three regiments and two batteries were left to hold the 600-yard gap between their right flank on the Emmitsburg Road and the rest of the II Corps on Cemetery Ridge. General Hancock re-formed the II Corps along the ridge while a new assault was made on the Union right. Hancock sent in Hays’ reserve brigade and their arrival on East Cemetery Hill helped break the Rebel foothold there and secure the Union line. As their scattered force streamed back to the Bliss farm, the Confederate officers attempted to re-form the brigade in the dark when they were ordered back to Seminary Ridge.

Day Three

At 7:30 am on July 3, the Mississippi troops were again inflicting casualties on the Union skirmish line. The remaining 12th New Jersey companies drove out the Confederates once again, but they were forced to withdraw almost immediately and the buildings once again fell into Rebel hands. By mid-morning the Bliss buildings had been captured three times with little result except the capture of prisoners.

Recognizing the desperate situation, General Hays sent orders to torch the buildings. Armed with cartridge papers and matches, men of the 14th Connecticut Infantry made their way across the fields to the barn, where hay and straw were soon on fire; in the farmhouse straw beds were emptied on the floor and set ablaze. The buildings at Bliss Farm burned to the ground, and the family lost everything, except their lives.

During the ill-advised infantry assault that would forever be known as Pickett’s Charge, Hays’ division defended the right of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. One man reported that as the Confederates approached:

He [Hays] was riding up and down the lines in front of us, exhorting the boys to stand fast and fight like men… Once he rode by and said, “Boys, don’t let ’em touch these pieces,” and in a few minutes he rode back again laughing, sung out, “Hurrah, boys, we’re giving them hell,” and he dashed up to the brow of the hill and cheered our skirmishers.

Hays waited until the Southerners got entangled with the fences about two hundred yards away. Then he shouted “Fire!” and his entire line erupted in flame and smoke. Though outnumbered, with the help from infantry and artillery nearby, Hay’s division slaughtered the Rebels in their front.

When the smoke cleared, General Hays was unhurt, but two horses had been shot out from under him. With his flair for the dramatic, Hays grabbed a Confederate battle flag and dragged it in the dirt behind his horse.

After Gettysburg

Hays led his division at Bristoe Station (October 14, 1863) and Mine Run (November 27 – December 2, 1863). His last major engagement as a division commander was at Morton’s Ford on the Rapidan River in Virginia on February 6, 1864. A demonstration in force by the II Corps became a bloody fiasco with Hays’ division suffering 252 casualties. Stories about Hays being drunk on duty arose. When the Union Army was reorganized in March 1864, Hays was reduced to brigade command. Hays was unhappy at losing division command but was glad to be serving under General David Birney.

General Ulysses S. Grant’s 1864 spring offensive against General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia became known as the Overland Campaign, and its first battle was fought at the Wilderness, a dense forest near Fredericksburg, Virginia.

On the morning of May 5, 1864, the Union V Corps attacked CSA General Richard Ewell‘s Corps on the Orange Turnpike. Later in the day CSA General A.P. Hill‘s Corps encountered USA General Hancock’s II Corps on the Plank Road. Fighting was fierce as both sides attempted to maneuver in the dense woods until darkness called an end to any further maneuvers.

Early on May 6, Hancock attacked Hill’s Corps and drove them back along the Plank Road until General Longstreet’s Corps arrived and prevented the collapse of the Confederate right flank. At noon, a devastating Confederate flank attack was halted when Longstreet was wounded by his own men.

Image: General Alexander Hays Monument

Image: General Alexander Hays Monument

Near Ziegler’s Grove, Gettysburg National Military Park

A standing portrait of General Hays holding a sword in each hand

Death at the Wilderness

In an action near the intersection of the Brock and Plank Roads in the Wilderness, General Alexander Hays was shot in the head with a Minie ball. One of his aides reported that he was shot in the temple as he was drinking from his canteen. His body was recovered and sent to the rear for transport home.

General Hays was buried in Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. While campaigning for the presidency, Ulysses S. Grant stopped in Pittsburgh and visited Hays’ grave. The gallant Grant openly wept at the loss of his friend.

Annie Adams McFadden Hays died in 1890.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Alexander Hays

Fold3 by Ancestry: Alexander Hays

Civil War Monitor: An 1863 Valentine

Genealogy.com: Annie Adams McFadden