Wife of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney

Anne Key (1783-1855) was the sister of Francis Scott Key, who wrote the words to our national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner, during the dramatic bombardment of Baltimore’s Fort McHenry in the War of 1812. She was also the wife of Roger B. Taney, the eleventh United States Attorney General and the fifth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864.

Anne Key (1783-1855) was the sister of Francis Scott Key, who wrote the words to our national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner, during the dramatic bombardment of Baltimore’s Fort McHenry in the War of 1812. She was also the wife of Roger B. Taney, the eleventh United States Attorney General and the fifth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864.

Image: Anne and Roger Brooke Taney House

Frederick, Maryland

The property includes the house, detached kitchen, root cellar, smokehouse and slave quarters in the rear, and interprets the life of Roger and Anne Key Taney, who lived here until 1821, as well as various aspects of life in early nineteenth century Frederick County.

Anne Phoebe Charlton Key was born on June 13, 1783, in Frederick County, Maryland. She was the daughter of Anne Phoebe Penn Dagworthy Charlton and wealthy farmer John Ross Key. Roger Brooke Taney (taw’-ny) was born on March 17, 1777, and raised at the family home in Calvert County, Maryland – Taney Place, a two-story Georgian-style country house, dating from about 1750.

Taney was the son of Monica Brooke Taney and Michael Taney, head of a prominent and aristocratic tobacco‐growing family whose politics were pro‐Constitution, pro‐Federalist and strongly supportive of the rights of private property. Growing up, Taney received lessons from a private tutor. In 1792, at the age of 15, Taney was sent to Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where he studied and lived with the difficult but brilliant Dr. Charles Nisbit, president of the college. Taney’s father asked Nisbet to become Taney’s guardian while he was away at school, since he was one of the youngest students there.

In the spring of 1795, Taney passed the oral examination required for graduation and was voted valedictorian by his classmates. It was an honor he had wanted but did not relish achieving. Taney was painfully shy, and public speaking was difficult for him throughout his life, upsetting his somewhat delicate health. Taney was a thin, flat-chested youth with thick black hair, solemn eyes, and a face that showed much character but was not handsome.

From 1796 to 1799, Taney clerked in the office of a prominent Annapolis judge. During this time, he made friends with Francis Scott Key, later famous for his poem The Star-Spangled Banner. After being admitted to the bar in 1799, Taney tried practicing in several locations, but finally moved to Frederick, Maryland, in March of 1801, where he remained for the next twenty years.

Frederick was a small town, but there were old family friends and relatives in the vicinity. Taney accepted all types of cases and was soon the most prominent lawyer in the area. During this time, he courted Anne Key, sister of his friend Francis Scott Key, who lived nearby at Terra Ruba, the Key family estate north of Toms Creek in Frederick County, Maryland.

By 1805, he was secure enough financially to propose, and Anne Key married Taney on January 7, 1806, at Terra Ruba. Anne was a kind and tranquil person who soothed Taney when his nerves were frayed, nursed him when his health was bad, and was a great comfort to him all their married life.

Taney was Roman Catholic; Anne was Episcopalian. They reconciled religious differences by agreeing that sons would be raised as Catholics, daughters as Episcopalians. The Taneys had six daughters, Anne (born in 1809), Elizabeth (born in 1811), Ellen (born in 1814), Sophia (born in 1818), Maria (born in 1819) and Alice (born in 1828). Their only son died in infancy.

By 1823, when Taney was forty-six, he had acquired a statewide legal reputation and an increasing amount of business requiring him to be in Baltimore. To advance his career, he sold his practice and home and moved to Baltimore. He had many wealthy clients, and by 1827, he was so well-known that the governor selected him for the prestigious post of state attorney general. He held that post and continued his private practice until 1831.

Taney remained active in politics, and joined the Jacksonian Democrats when the Federalist Party expired, and led Andrew Jackon’s presidential campaign in Maryland. On December 27, 1831, Jackson appointed Taney U.S. Attorney General.

In the cabinet, he became one of President Jackson’s most trusted counselors and was then appointed Secretary of the Treasury in September 1833, but Congress rejected Taney, the first time that Congress had refused to confirm a presidential nominee for a Cabinet post. Taney returned to Baltimore to rebuild his law practice.

Fifth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

In 1835, President Jackson nominated Taney to replace Gabriel Duvall as associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, but the Senate postponed the confirmation vote indefinitely. Chief Justice John Marshall died in December 1835. In March 1836, with the Senate back under Democratic control, President Jackson nominated Taney as Chief Justice.

Taney was commissioned on March 15, 1836 and sworn in on March 28, 1836 as the fifth Supreme Court Chief Justice, a position he held for 28 years – from 1836 to 1864. Since Taney was so different from Chief Justice Marshall, it took time for Taney to earn the respect of his fellow justices and members of the legal community, however he proved himself an able constitutional theorist and judicial leader.

In short, Taney’s judicial opinions as Chief Justice reversed a pattern established by Marshall. Instead of emphasizing federal supremacy, Taney upheld state sovereignty, especially in relation to the threatened domination of the South by the North. Several of the cases in 1837 showed the difference between Taney’s view of the constitution and that of his predecessor, who had been more and more drawn to allow a wide scope to the powers of congress.

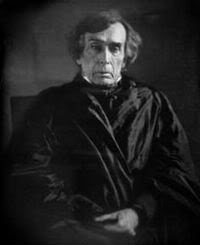

Image: Chief Justice Roger B. Taney

The Dred Scott Decision

Taney made significant contributions to American constitutional law, but the case most closely associated with him inflicted enormous injury to the Court as an institution. That case was Dred Scott v. Sandford, which involved the question whether congress had the power to exclude slavery from the territories.

In 1846, a slave named Dred Scott sued his master for his freedom. In 1850, the Missouri Circuit Court granted Scott’s request and declared him a free man. However, the widow of his former master appealed the case to the Missouri Supreme Court, which overturned the ruling and pronounced Scott a slave, and as a slave he could not file suit in court.

By 1854 the case had made its way to the Supreme Court, and after being argued twice, it was finally decided on March 6, 1857. The opinion of the court was written by Chief Justice Taney.

The Dred Scott decision showed Taney’s view of state supremacy: he ruled that a slave under Missouri law had no constitutional right to bring suit in federal court. Part of his decision stated:

It is difficult at this day to realize the state of public opinion in regard to that unfortunate race which prevailed in the civilized and enlightened portions of the world at the time of the Declaration of Independence, and when the Constitution of the United States was framed and adopted; but the public history of every European nation displays it in a manner too plain to be mistaken.

They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect, and that the Negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.

Later in the decision, Taney stated that the Missouri Compromise and other laws of Congress that inhibited slavery in the territories of the United States were unconstitutional, and that whatever measure of freedom Dred Scott may have acquired by his residence in Illinois, he lost by being subsequently removed to Wisconsin, and by his return then to Missouri.

The decision produced a strong reaction from citizens all around the country. Taney’s family had owned slaves since their arrival in the colonies in the seventeenth century, but his personal attitude toward slavery was more complex. In 1819, he had condemned slavery as “a blot on our national character.” Taney emancipated his own slaves and gave pensions to those who were too old to work.

Anne Key Taney died in Baltimore on September 29, 1855, from complications of a stroke which had left her paralyzed. She was buried at Saint Johns Catholic Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland. The Taneys’ youngest daughter, Alice, died the next day from yellow fever.

Abraham Lincoln condemned of the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision during his campaign debates with Senator Stephen A. Douglas, which helped to set the tone for a tumultuous relationship with Taney. In 1861, Taney challenged Lincoln’s authority and decision to suspend habeas corpus, but Lincoln ignored Taney’s demands and focused his attentions on the war.

Taney administered the oath of office to Abraham Lincoln, his most prominent critic, on March 4, 1861. Taney continued to trouble Lincoln during the three years he remained Chief Justice after the beginning of the Civil War. After Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus in parts of Maryland, Taney ruled that only Congress had the power to take this action. Lincoln ignored Taney’s order and continued to have arrests made without the privilege of the writ. When the matter was finally decided by after Taney’s death, Taney was fully vindicated and an important new rule of law was established.

Taney was an old, sick man when the Civil War began, and few members of the Lincoln Administration had anything but scorn for him. There were other attempts by Taney to restrain the federal government’s exercise of arbitrary power, and each time, he was attacked by the press. Taney remained the Supreme Court Chief Justice until his death, giving him the second-longest tenure of any chief justice.

Taney spent his final years in worsening health, near poverty, and despised by both North and South. He lost his Maryland estates to the Civil War and suffered from poverty. The miserable financial situation was maddening to him. “All my life I have felt the obligation to pay my debts… and my inability to do so at this time is mortifying.”

Taney’s annual salary was approximately $10,000. In the inflationary Washington, DC, of this time, the yearly rent for his boardinghouse rooms had jumped from $4,000 to $8,000, with no increase in pay. He was prevented from moving to cheaper quarters due to the failing health of his daughter Ellen, who lived with him.

In the fall of 1864, a chronic intestinal disorder from which he had suffered for some years became acute and violently painful. Roger Brooke Taney died on October 12, 1864, in Washington, DC, at the age of 87. As he had requested, the funeral service was a quiet and modest affair, all the more so because most Republican cabinet officers refused to attend.

Reflecting on the legacy and impact of Chief Justice Taney, his work on the bench was not respected by all. In the preface for his book The Taney Court, author Timothy S. Huebner says:

After the death of Chief Justice John Marshall, many Americans viewed Taney as a poor replacement for Marshall, who had already achieved the status of mythic greatness in some quarters. Taney, in contrast, seemed too much a product of the rough-and-tumble politics of the age and too closely tied to the president who appointed him. President Andrew Jackson, the self-proclaimed champion of the so-called common man, had elevated Taney to the bench after the lawyer had served extraordinarily controversial stints as U.S. attorney general and secretary of the treasury.

Taney was remembered positively by some. Judge William Fell Giles of the United States District Court in Maryland said this in his memorial to Taney:

For eleven years I have been associated in the Federal Court in this State with this great man… Now, when he has passed away and no work of mine can offend his modesty, I can truly say that I have never known a purer or better man, one who loved his country more, or whose heart was more alive to every warm and generous feeling of our nature.”

It should be remembered that during the decades when Taney served on the Court, it was a time of great social change in America – culturally, socially and politically. The issue of slavery was the downfall of the Court and detracted permanently from the image of Taney’s statesmanship.

SOURCES

Roger Brooke Taney

Wikipedia: Roger B. Taney

Catholic Encyclopedia: Roger Brooke Taney

Goodreads.com: The Taney Court, 1836-1864