Wife of Union General William Rosecrans

Ann Eliza Hegeman, the daughter of New York City judge Adrian Hegeman, was from an old and prosperous family. William Starke Rosecrans attended West Point, where he excelled in planning military maneuvers and he was considered brilliant in mathematics. He graduated from West Point in 1842, fifth in a class of 56 cadets, which included notable future generals such as Dana Harvey Hill, James Longstreet, and Don Carlos Buell.

Ann Eliza Hegeman attended graduation at West Point with friends. After the ceremonies, Rosecrans invited her to go for a walk and they immediately fell in love. William Mathias Lamers, author of The Edge of Glory: A Biography of General William S. Rosecrans (1961), states that the many letters exchanged by the couple were “full of love.”

Marriage and Family

On August 24, 1843, Ann Hegeman married William Rosecrans at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City. Following the wedding, First Lieutenant Rosecrans was appointed Assistant Professor of Engineering and later Assistant Professor of Philosophy. These were difficult times in the Rosecrans home. Their first child, William was born in 1845 but died soon after. Another boy James Addison also died right away.

In 1847 William was sent to design and rebuild fortifications along the east coast and moved the family to Newport, Rhode Island. Adrian Louis was born there May 28, 1849 and Mary Louise in 1851.

From April through December 1853, Rosecrans was a Civil and Construction Engineer at the Washington Navy Yard. The family was happy there but money was tight. Ann’s mother Eliza Hegeman lived with William and Ann, and her money helped the family survive the lean years. Eliza continued to reside with them until she died in Mexico while the General was the Minister to Mexico in the late 1860s.

William often drove himself to the point of exhaustion and his health sometimes failed. After a leave of three months in early 1854, Rosecrans’ health had not improved enough for him to continue in the the military so he resigned. Twenty days after leaving the army, Lily Elizabeth joined the family in Cincinnati on April 21, 1854.

Still not completely recovered, Rosecrans worked as an architect and consulting engineer until June 1855 when he took charge of the Cannel River Coal Company’s mining interests in Kanawha County, Virginia (now West Virginia). At least part of this time the family lived in Wheeling where Anna Dolores (sometimes called Anita) was born. Rosecrans decided to go into business on his own, and in 1857, he organized the Preston Coal Company.

William’s brother, Sylvester Horton Rosecrans, had been ordained in Rome in 1852 and after touring through Europe, he was assigned to the Archdiocese of Cincinnati as pastor of St. Thomas Church. He was then appointed as a professor at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary of the West; he became president of the college in 1856. William probably moved his family to Cincinnati to be near his brother.

In Cincinnati’s 1858 city directory, the Rosecrans family lived at 385 George Street, and William is listed as a coal manufacturer at 423 West 2nd Street. Still sometimes working himself too hard, he worked for 16 days straight, attempting to develop pure and odorless oil. When he was about to succeed, one of the glass lamps he had purchased exploded and badly burned him.

He spent the next 18 months in bed recovering. The burns left him scarred on the right side of his face. Therefore, most photographs show him turned to the right, to hide the scars. He returned to his business as soon as he was able. His partners were honorable men, but they were not chemists. The business was not successful.

Rosecrans worked on several other inventions, like wicks for oil lamps, hoping to hit on something that would succeed. Two of the few patents issued to Rosecrans came through just before the war. Ann E. Rosecrans witnessed both patent applications. Henry Howe, in his Historical Collections of Ohio, noted:

During all these years of his early career he exhibited, in the limited fields open to him, those characteristics of original conception, inventive genius, restless activity and tireless energy which were ever afterwards to carry him through a career of wonderful success at the head of great armies and enroll his name amongst those of the most brilliant soldiers known to military history.

Civil War

On April 14, 1861 Fort Sumter was attacked. On April 19, Rosecrans traveled to Columbus and offered his services to Governor William Dennison, Jr. President Lincoln signed the commission promoting Rosecrans to the rank of Major General on September 17, 1862, as the Battle of Iuka (Mississippi) was being fought.

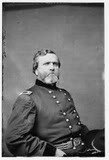

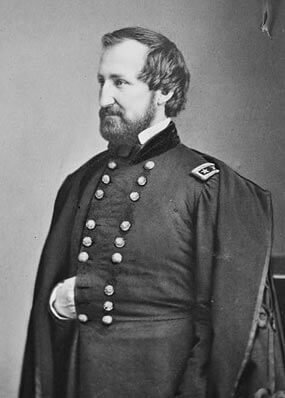

Image: General William Rosecrans

Rosecrans defeated General Earl Van Dorn and General Sterling Price in the Second Battle of Corinth on October 3 and 4, 1862. After the battle, General Ulysses S. Grant was disgusted with Rosecrans because he did not pursue the enemy after they were defeated. Rosecrans insisted he was never given those orders, and no such orders appear in the Official Records. The whole matter was magnified because the two generals simply did not like each other. General Grant wrote in his memoirs that:

[Rosecrans] failed to follow up the victory, although I had given specific orders in advance of the battle for him to pursue the moment the enemy was repulsed; he did not do so, and I repeated the order after the battle.

Home and Family

Ann and the children were staying with the wife of Eliakim Parker Scammon in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Scammon and Rosecrans had been friends since West Point. During the battle, Rosecrans received word that Ann, who had been dangerously ill, was recovering, but their baby (Charlotte) had died. Hoping to improve Ann’s spirits, he wrote a letter describing the truce he had made with Van Dorn at Holly Springs: “[The Confederates] have a wholesome regard for me, praise very highly the style of our troops and the tactics on the field of battle. They are more afraid of me than any other general in service. Thanks be to God for that.”

Army of the Cumberland

On October 24, 1862, Halleck ordered General Rosecrans to take command of the Army of the Cumberland, outlining what was expected of him and his new force:

The great objects to be kept in view in your operations in the field are: First, to drive the enemy from Kentucky and Middle Tennessee; second, to take and hold East Tennessee, cutting the line of railroad at Chattanooga, Cleveland, or Athens, so as to destroy the connection of the valley of Virginia with Georgia and the other Southern States. … by prompt and rapid movements a considerable part of this may be accomplished before the roads become impassable from the winter rains. … You will fully appreciate the importance of moving light and rapidly, and also the necessity of procuring as many of your supplies as possible in the country passed over. … I need not urge upon you the necessity of giving active employment to your forces. Neither the country nor the Government will much longer put up with the inactivity of some of our armies and generals.

Rosecrans, setting up headquarters in Bowling Green, Kentucky, found his new command in a disorganized state. He believed that his army needed to be reorganized before beginning a new operation; he obtained permission to muster out officers guilty of drunkenness and pillaging. Therefore, Rosecrans’ Army remained in Nashville, 30 miles north of General Braxton Bragg’s troops, until December. Halleck was incensed.

Battle of Stones River

The Northern and Southern armies finally approached each other along Stones River near Murfreesboro on December 31, 1862. Rosecrans brought 42,000 Union soldiers to the battlefield; with his 35,000 men, Bragg attacked the right Yankee flank in the numbing cold and fog of a wintry Tennessee morning. Bragg was initially successful in driving the Unionists back, but could not break the Yankee line. Hard fighting throughout the day resulted in heavy casualties, and the wounded suffered even more due to the frigid weather.

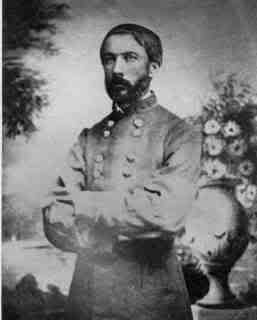

Image: General George Maney’s Brigade

Lurking just inside the tree line during the Battle of Stones

When New Year’s Day dawned both armies were still in the field and continued the fight to another stalemate. On January 2, 1863, against the advice of his generals, Bragg attacked Rosecrans; Union troops repelled the assault and forced Bragg back to Tullahoma, Tennessee. The North now controlled Middle Tennessee, and the Union victory boosted Yankee morale after the disastrous loss at Fredericksburg a few weeks earlier.

Both armies suffered some of the highest casualty rates of the war, the Union suffering 13,000 killed, wounded or captured; the Confederates about 10,000 – approximately one-third of their fighting force. The Army of the Cumberland took six months to recover. President Abraham Lincoln wrote to Rosecrans, “you gave us a hard victory which, had there been a defeat instead, the nation could scarcely have lived over.”

Battle of Chickamauga

Rosecrans would meet Braxton Bragg again in September 1863, as Union and Confederate forces were struggling to control the key railroad center at Chattanooga, Tennessee. Rosecrans thought he had maneuvered Bragg to the south, completely out of Tennessee, but Bragg was not retreating. He was luring Rosecrans into North Georgia. Reinforcements led by General James Longstreet were on the way from Virginia, which would improve Bragg’s forces tremendously, and he decided to fight Rosecrans in northwest Georgia.

The armies met in the woods along the banks of Chickamauga Creek on September 19. All day Bragg’s men assaulted the Union line, but could not break it. On the morning of September 20, General Rosecrans, whatever the reason, believed there was a gap in his line of battle. He immediately issued an order to General Thomas Wood “to close in and support his left.”

The execution of Rosecrans’ order, as he wrote it, actually created a huge gap in the line. About the same time, Longstreet arrived and ordered General John Bell Hood to prepare for an attack. About 11:30, Hood’s troops struck the federal line, just as General Wood finished moving his men to plug Rosecrans’ gap. The Confederates poured through the hole and wheeled to the right, rolling up the Union line as they advanced.

From his headquarters in the tiny cabin of Widow Eliza Glenn, Rosecrans tried to hurry General Philip Sheridan into the gap, but his men were more than a mile away. Hood’s men came so close to Rosecrans’s new headquarters at Widow Eliza Glenn’s cabin that the staff officers inside had to shout to make themselves heard over the sounds of battle.

The Rebels sent the Union troops into a chaotic retreat toward Chattanooga. Generals Rosecrans, McCook and Crittenden were cut off from their troops. They followed a farm road to the west and made their way to Chattanooga. General George Thomas organized the remaining Federals in a desperate Union stand, and they made an orderly retreat to Chattanooga back to Chattanooga. For his actions and bravery, Thomas earned a lasting reputation as the Rock of Chickamauga.

Thomas later urged Rosecrans to take control of the army again, but Rosecrans appeared to be a broken man; he remained in Chattanooga. President Lincoln told his secretary John Hay that Rosecrans seemed “confused and stunned like a duck hit on the head.” The president telegraphed Rosecrans:

Be of good cheer. … We have unabated confidence in you and your soldiers and officers. In the main, you must be the judge as to what is to be done. If I was to suggest, I would say save your army by taking strong positions until Burnside joins you.

On September 29, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered General Grant to go to Chattanooga and take command of the Military Division of the Mississippi. Stanton gave Grant the choice of retaining Rosecrans as commander of the Army of the Cumberland or replacing him with Thomas; Grant chose Thomas.

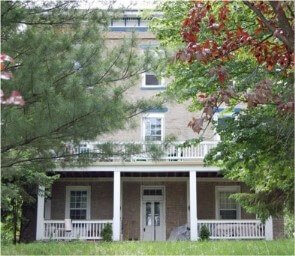

Rosecrans House

Union officials sent General Rosecrans home to Cincinnati to await further orders. At that tine, Ann Rosecrans and the children were living in a large stone house called Rocabella. William’s brother, Father Sylvester Rosecrans, was president of Mount St. Mary’s Seminary of the West, which was nearby, and he often spent his afternoons at Rocabella playing and reading with the children.

Image: Rosecrans House at Rocabella

Image: Rosecrans House at Rocabella

2935 Lehman Road in Price Hill

Cincinnati, Ohio

Rocabella had a beautiful old fashioned garden and a large grape arbor, a raspberry patch and numerous walks with roses, hollyhocks, marigolds and lilies. Price Hill Historical Society says the home at 2935 Lehman Road is Rocabella, where the Rosecrans family lived during the Civil War. The sturdy thick-walled stone house had been built high on a hilltop in 1850 and its rear windows overlook the Ohio River. A tunnel running through the backyard and a sub-basement indicate that it was probably used as a station on the Underground Railroad before the Civil War.

The Union Army assigned General Rosecrans to command of the Department of Missouri, where he spent the remainder of the war in relative obscurity. When William left for his new assignment, the family could not go with him, but Father Sylvester stepped in to help Ann with the children.

After the War

After the war Rosecrans moved to California and resumed his career in business. He was appointed Minister to Mexico in 1868. After his election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1880, Rosecrans moved his family to Washington DC. He chaired that body’s Military Affairs Committee but resigned from Congress in 1885 to accept an appointment as Register of the Treasury, where he served until 1893.

On Christmas Day 1883, Ann Eliza Rosecrans died, probably of cancer. She had outlived five of her children but did not live to see the addition of any grandchildren.

William Rosecrans died of pneumonia at Redondo Beach, California, March 11, 1898. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

David Henderson, Speaker of the House of Representatives spoke at Rosecrans interment in Arlington National Cemetery:

I had the pleasure of serving under his command at the battle of Corinth, and also served with him in the House of Representatives… He was one of the most fearless officers that I ever saw in battle. He seemed to be unconscious of danger. On the fourth of October 1862, when the armies of Price and Van Dorn were pressing our lines and symptoms of our falling back were manifest, he suddenly dashed between the Federal and Confederate lines… Swinging his sword he called out to us: “Stand by your flag and country, my men!” How he escaped, God only knows. … fearless he rode into the very teeth of death, rallying successfully his men for the mighty struggle before them. That splendid, fearless, heroic dash was the death-knell to the armies of Price and Van Dorn.

SOURCES

History.com: Battle of Stones River

History.com: Battle of Chickamauga

About North Georgia: William S. Rosecrans

Civil War Trust: New Year’s Hell, The Battle of Stones River

Rosecrans Headquarters: Major General William Starke Rosecrans