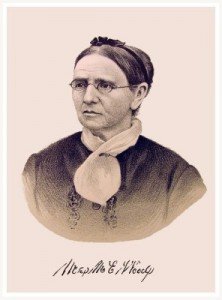

Civil War Nurse from Washington DC

Carte de Visite of Almira Fales

Carte de Visite of Almira Fales

From the Civil War era

Almira Newcomb was born in Pittstown, New York, October 24, 1809. In 1829, she married merchant Alexander McNaughton. Together they had two children; Sarah (born 1830) and Alexander (born 1832). Not long after her son’s birth, both her husband and young daughter died.

In 1837, Almira married an older widower, Leander Lockwood of Connecticut, who had five children from his first marriage. In 1840 or 1841, they left Connecticut for Burlington, Iowa, where they ran a hotel. While there, Almira had two more children, Charles and Thomas Hartbenton.

Leander Lockwood died in 1845, leaving Almira with eight children: Alexander from her first marriage, Charles and Thomas from her second marriage and five Lockwood step-children. With a family to support, she applied to the Mission School of the Winnebago Indian Agency at Fort Atkinson, Iowa, and secured a position as a teacher of domestic economy for two years.

Joseph Fales was then the Auditor for the State of Iowa and a widower with three children of his own. During his work, he and Almira met. In 1847, they married and returned to Burlington, Iowa. When Mr. Fales was offered a position as an Examiner at the United States Patent Office in 1853, they moved to Washington, DC.

When rumors of impending war increased during 1860, Almira Fales was the first to begin collecting bandages and lint. She was scoffed at for this. The North would not believe in the possibility of war until the Confederate guns fired on Fort Sumter.

Civil War

When the men of the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment were attacked in the Baltimore Riot April 19, 1861, Almira Fales rushed to meet the train carrying the wounded soldiers when it arrived in Washington.

When the United States Sanitary Commission was formed in June 1861, Fales was recruited by Frederick Law Olmsted, one of the Commissioners. She was given two ambulances to transport the wounded to hospitals. She also personally tended to the wounded, searched for lost soldiers and did all in her power to insure that those being cared for in the hospitals received the best of care.

In the yard of her own house in Washington DC, she pitched a large tent, into which she gathered sick and disabled soldiers, and there ministered to their needs until means could be provided to send them to their homes. For some time Fales was charged by the government with the superintendence of soldiers sent from the hospitals in and around Washington to the hospitals in New York and elsewhere.

When it was necessary for the men to be returned to hospitals closer to their homes, Fales often accompanied them on the train or steamship for those long journeys home, sometimes being the only woman on board. In addition to all that, she supplied personally between sixty and seventy forts with reading materials.

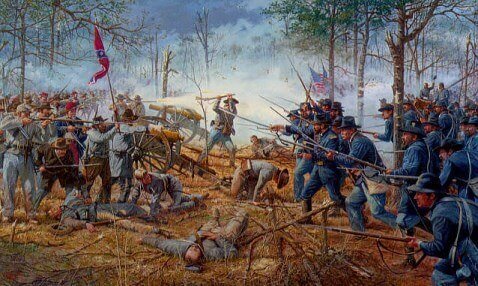

Image: The Hornet’s Nest by Dale Gallon

Image: The Hornet’s Nest by Dale Gallon

Battle of Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee

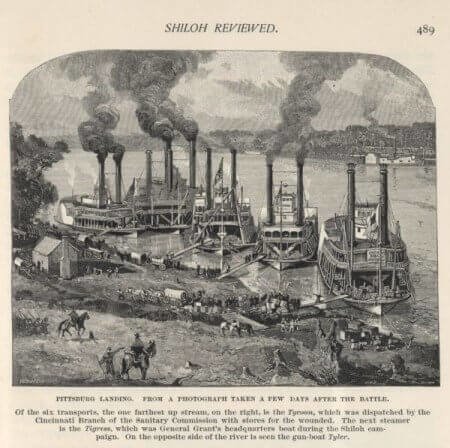

Pittsburg Landing

The Battle of Pittsburg Landing was a bloody two-day conflict. On the morning of April 6, 1862, forty thousand Confederate soldiers of the newly christened Army of the Mississippi under the command of CSA General Albert Sidney Johnston poured out of the nearby woods and attacked USA General Ulysses S. Grant‘s forces near Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River. The surprise attack almost overwhelmed the Federal troops, but they recovered and established a battle line at the sunken road, named the Hornet’s Nest by the Confederates.

The Federals held their position until after dark, when the fighting finally ended. General Johnston had been mortally wounded and was replaced by General P.G.T. Beauregard. Reinforcements for the Federal army arrived during the night, and Grant’s counterattack the following morning eventually swept Beauregard’s army from the field. The two day battle at Pittsburg Landing produced more than 23,000 casualties and was the bloodiest battle in American history up to that time.

Several steamships that had been outfitted for use as hospital ships by the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) were docked at Pittsburg Landing during and after the battle. The Chicago Branch of the USSC sent the hospital boat Louisiana while the Cincinnati Branch sent the Tycoon and the Monarch. Each boat was complete with surgeons, volunteer nurses, medical supplies, bedding, clothing and food.

In the early stages of the operation, Almira Fales was often the only woman nursing the wounded and dying men on these hospital transport ships. Wounded were brought onboard and made as comfortable as possible for the trip North to large military hospitals where they could receive top-notch care. As soon as a ship was filled, another took its place. Boatload after boatload headed downstream to hospitals in Keokuk, St. Louis, Louisville, Mound City, Evansville, Cincinnati and Paducah.

Image: Pittsburg Landing, from a photograph taken a few days after the battle

Caption: Of the six transports, the one farthest upstream, on the right, is the Tycoon, which was dispatched by the Cincinnati Branch of the Sanitary Commission with stores for the wounded. The next steamer is the Tigress, which was General Grant’s headquarters boat during the Shiloh Campaign. On the opposite side of the river is seen the gunboat Tyler.

On to the Peninsula and Beyond

During the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia (March through July 1862), Fales was on board the hospital ships much of the time. She was under fire through the Seven Days Battles (June 1862), ministering on those bloody fields to “the saddest creatures that she ever saw.” She was at Harrison’s Landing (July 1862) caring for the wounded and wearied men worn down by the incessant battles and hard marches, and when the Union Army changed its base of operations from the Chickahominy to the James River.

She spent considerable time in hospitals at Fortress Monroe, Virginia. She was active on the battlefields of General John Pope’s campaign in Virginia in the autumn of 1862, including Second Bull Run (August 1862) and Chantilly (September 1862). She was at Corinth, Mississippi (October 1862), and back in Virginia at Fredericksburg in December 1862.

During the Chancellorsville Campaign (May 1863), Almira Fales lost a son. On May 3, 1863, Thomas Hartbenton Fales, a corporal in the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry, was killed in the Battle of Salem Heights. As devastating as his death must have been, she was prevented from recovering his body for burial. In addition, she also had the worry for her other son Charles who was also serving in the Union army.

On July 22, 1863, a little more than two months after her son’s death, Fales wrote to friend and fellow Civil War nurse Eunice Cook:

I feel now that I must work harder and do more for the living than I have ever done, and to this end I go daily 6, 8, 10 or 12 miles to the distant camps, forts and hospitals where a female is seldom seen, and furnish the sick and suffering boys with all the things you good ladies are sending me from time to time. I wish I could do more.

Excerpt about Almira Fales from Woman’s Work in the Civil War:

For her, to be a soldier’s nurse meant something very different from wearing a white apron, a white cap, sitting by a moaning soldier’s bed, looking pretty. It meant days and nights of untiring toil; it meant the lowliest office, the most menial service; it meant the renouncing of all personal comfort, the sharing of her last possession with the soldier of her country; it meant patience, and watching, and unalterable love.

A mother, every boy who fought for his country was her boy; and if she had nursed him in infancy, she could not have cared for him with a tenderer care. Journey after journey this woman has performed to every part of the land, carrying with her some wounded, convalescing soldier, bearing him to some strange cottage that she never saw before, to the pale, weeping woman within, saying to her with smiling face, “I have brought back your boy. Wipe your eyes, and take care of him.” Then, with a fantastic motion, tripping away as if she were not tired at all, and had done nothing more than run across the street.

Thousands of heroes on earth and in heaven gratefully remember this woman’s loving care to them in the extremity of anguish. The war ended, her work does not cease. Every day you may find her, with her heavily-laden basket, in hovels of white and black, which dainty and delicate ladies would not dare to enter. No wounds are so loathsome, no disease so contagious, no human being so abject, that she shrinks from contact; if she can minister to their necessity.

In person she is tall, plain in dress, and with few of the fashionable and stereotyped graces of manner. No longer young, her face still bears ample traces of former beauty, and her large blue eyes still beam with the clear brightness of youth. She is full of a quaint humor, and in all her visits to hospitals her aim seemed to be to awake smiles, and arouse the cheerfulness of the patients; and she was generally successful in this, being everywhere a great favorite.

Additional information about Fales is unavailable at this time. She did not live long after the Civil War.

Almira Fales died November 8, 1868, in Washington, DC at age 59.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Almira Fales

Woman’s Work in the Civil War by L.P. Brockett and M.C. Vaughan

South Danvers Observer: Mrs. Almira Fales – PDF