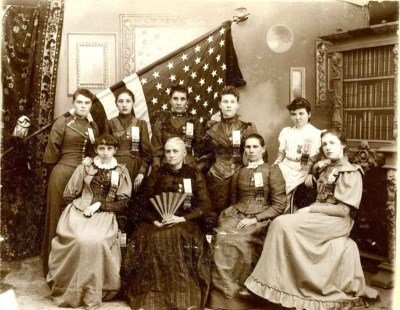

Patriots Who Volunteered to Aid Union Soldiers

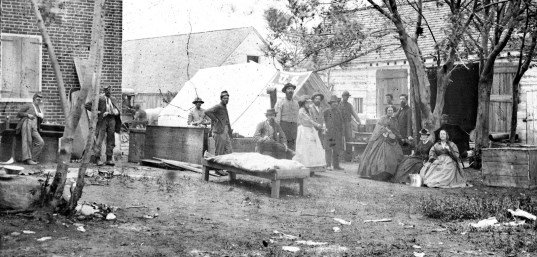

Image: Men and women volunteers in the backyard of the United States Sanitary Commission depot at Fredericksburg, Virginia

The U.S. Sanitary Commission opened hospitals, organized supplies and educated government officials. Women volunteers raised money, collected donations, made uniforms, worked as nurses, cooked in army camps, and served on hospital ships and at Soldiers’ Homes. They organized Sanitary Fairs in numerous cities to support the Federal army and the work of the USSC.

Backstory

Abraham Lincoln’s victory in the presidential election of 1860 triggered South Carolina’s secession from the Union in December 1860; ten other states would follow their lead in the coming months. Women throughout America held their collective breath. Reverend Dr. Henry Whitney Bellows, minister of All Souls Church Unitarian in New York City, expressed it well in a January 9, 1861 letter to his son Russell, a student at Harvard:

…we can think of nothing else! Nothing is interesting but the papers, and every night and morning I take them up eagerly and carefully to see whether we have a country or not!

After the attack on Fort Sumter, the president called for 75,000 troops to quell the rebellion April 15, 1861. Swept into action, women formed soldiers’ aid societies to cheer recruits who had enlisted from their communities with the comforts of home. The first organization of that kind appeared at Bridgeport, Connecticut. They raised money, gathered supplies, rolled bandages, sewed or knitted clothing, and provided financial support for soldiers’ families.

The federal government was far from being ready to care for thousands of injured soldiers, as illustrated in this excerpt from Caring for the Men: The History of Civil War Medicine:

When the war began, the United States Army medical staff consisted of only the surgeon general, thirty surgeons, and eighty-three assistant surgeons. Of these, twenty-four resigned to “go South,” and three other assistant surgeons were promptly dropped for “disloyalty.” Thus the medical corps began its war service with only eighty seven men.

While Northern officials frantically prepared for war, on their own initiative Union women began collecting, preparing, and making items for the troops. It soon became clear that the supply effort needed to be centralized and organized in order to avoid wasteful production and distribution. Mary Livermore, who would later become a United States Sanitary Commission manager, described the scene:

Baggage cars were soon flooded with fermenting sweetmeats… Decaying fruits and vegetables, pasty and cakes in a demoralized condition, badly canned soups and meats were thrown away en route. And with them went the clothing and stationary saturated with the effervescing and putrefying compounds which they enfolded…

Women’s Central Association for Relief

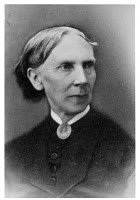

The situation was grim. Fortunately, women throughout the Northern states came forward, offering to help. In the first attempt to organize their efforts, on April 25, 1861, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, first American female doctor, held a meeting of fifty or sixty women at New York Infirmary for Women and Children, the hospital she had founded in 1857.

According to Katharine Prescott Wormeley, who later served as a nurse, Blackwell wanted “to organize the whole benevolence of women of the country into a general and central association.” To oversee operations a Board of twelve women and twelve men managers was created.

At that meeting Reverend Dr. Bellows called for a general association of New York City and its neighborhoods; he would invite all churches, schools, and aid societies to cooperate. Bellows summoned the women of New York to meet at Cooper Institute on April 29, where Bellows drew up the constitution of what became the Women’s Central Association of Relief (WCAR).

The Women’s Central Association of Relief (WCAR) would coordinate and organize the local relief efforts of northern women, communicate directly with the Army’s medical department about the soldiers’ needs, and perform the selection, registration, and training of women nurses.

WCAR Nurses

Training of nurses under Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell was one of the original objectives of the WCAR. In her struggle to become a doctor, Blackwell had learned that having the support of prominent men was important for success. Therefore, the WCAR asked Reverend Henry Bellows to take a committee of men to Washington, DC to meet with the Army Medical Department and the Secretary of War Simon Cameron.

After touring Union hospitals and seeing that many soldiers were in bad health, Bellows saw that there was also a need to work with the Army to improve the conditions, procedures and sanitation of Army hospitals and camps. Bellows and his colleagues proposed a civilian sanitary commission based upon the British Sanitary Commission in the Crimea.

The Army was at first resistant to working with a civilian group. In a letter to Secretary of War Cameron, Bellows pointed out how women everywhere wanted to support the troops, and described how the Commission would act as an intermediary between the military and the women who were offering their help:

The War Department will hereafter inevitably experience in all its bureaus the incessant and irresistible motions of [women’s] zeal, in the offer of medical aid, in the applications of nurses, and the contributions of supplies.

The Commission proposed to shield the Army by providing a masculine discipline, so that the women’s help would be “least hurtful to the army system.” President Abraham Lincoln signed this declaration on June 13, 1861.

In summary, WCAR was a vital force in collecting supplies and funds totaling more than $1 billion to support the Union troops. In the process, as its female managers traveled around the country and negotiated with civic organizations and businesses, the WCAR provided its workers unique opportunities to operate outside traditional expectations for women.

The Woman’s Central Association of Relief (WCAR) officially became a branch of the USSC June 24, 1862. Its primary function was the procurement of supplies, but it also participated in other war relief efforts, such as fundraising, registering female nurses for work in military hospitals, and helping to direct returning, discharged soldiers and soldiers’ families to local relief agencies for assistance.

United States Sanitary Commission

It soon became clear that Northern women’s efforts needed to be unified. From the work of the WCAR, a strong demand arose for the creation of a sanitary commission, which was also inspired by the British Sanitary Commission of the Crimean War.

In June 1861, the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) was created to help organize women’s volunteer work for the war. The Commission persuaded highly respected doctors to write pamphlets on sanitation and hygiene, which they circulated among both medical and line officers. Although often erroneous, these pamphlets reflected the best knowledge of bacteria at that time.

The Surgeon General of the United States had no desire for a sanitary commission, but when they promised to confine its activities to the volunteer regiments and to leave the regular army alone, he withdrew his objections. Secretary of War Simon Cameron then named a commission of twelve members, of whom three were army doctors.

The USSC quickly extended itself into 2,500 communities. Prominent women in the organization – Louisa May Alcott, Almira Fales, Eliza Chappell Porter, Katherine Prescott Wormeley – often traveled great distances and worked in harsh conditions. Thousands of local aid societies across the North and West supported the Commission by sending shirts, socks, and uniforms for soldiers, and hospital supplies, which were then re-packaged and sent where they were needed most.

In order to administer the network of aid at the local level, twelve local branches of the Sanitary Commission were created; there were branches in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, Louisville, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, New Albany, Detroit, and Columbus, and all were run by women with a variety of backgrounds and skills.

USSC Nurses

Most females of the age had some basic knowledge of home health care, but those who volunteered as Union nurses learned to provide medical care in military hospitals on the job. No examples, models, or precedents existed; these women blazed their own trail. When nurse Hannah Ropes learned that an army surgeon was mistreating a boy at the hospital where she worked, she went directly to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and he had the surgeon taken to prison.

Women were considered natural nurses because of their compassion and motherly instincts. A strong-minded but gentle woman called Mother by her soldier boys, Mary Ann Bickerdyke was an experienced nurse in her mid-forties. She became so popular that General William T. Sherman officially appointed her to his corps hospital. After she accused a surgeon of wrongdoing and he complained to General Ulysses S. Grant, Grant told the surgeon:

My God, man, Mother Bickerdyke outranks everybody, even Lincoln. If you have run amok of her, I advise you to get out quickly before she has you under arrest.”

Elizabeth Blackwell was not given a role in the USSC, nor was she asked to join as a medical advisor, even though she had been so instrumental in the formation of the WCAR. Her sister Dr. Emily Blackwell was not asked to participate either. Elizabeth wrote to her friend Barbara Bodichon:

You will probably not see our names… the doctors would not permit us to come forward… and refused to have anything to do with the nurse education plan if the “Miss Blackwells were going to engineer the matter.”

Helen Gilson of Chelsea, Massachusetts served as a nurse in the Sanitary Commission. She supervised supplies, dressed wounds, and cooked special foods for patients who were on special diets. She worked in hospitals after the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. She was also a successful administrator, especially at the hospital for African American soldiers at City Point, Virginia.

Over time, the work of the USSC changed people’s minds about women’s roles in medicine. Prior to the Civil War, women had been discouraged from pursuing a medical career, but within a year, Surgeon General Hammond began allowing local surgeons to hire women to fill up to one-third of the nursing roles in their hospitals. As a result, more than 15,000 Union women were employed as nurses in the War.

Women of the USSC

Middle class women who volunteered as nurses were rewarded with a sense of patriotism. Women like philanthropist Annie Wittenmyer, president of the Iowa State Sanitary Commission, played leadership roles. Some wrote memoirs of their experiences, including Sarah Palmer Young and Sarah Emma Edmonds. Tens of thousands of others worked for Union troops as well. Most were anonymous, sewing clothing or gathering supplies.

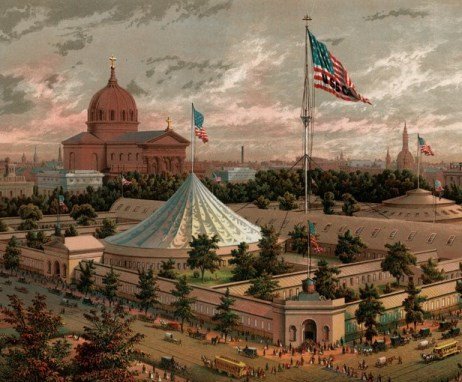

Image: Buildings of the Great Central Fair

Image: Buildings of the Great Central Fair

June 1864

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Sanitary fairs were civilian-organized bazaars and expositions dedicated to raising funds on behalf of the USSC. One of the largest and most successful of these events was the Great Central Fair held in Philadelphia from June 7 to June 28, 1864, to raise money for the Sanitary Commission.

On March 18, 1864, President Lincoln stood in front of a crowd of thousands at the closing ceremonies of the Washington, DC Sanitary Fair. This event and others like it around the country had raised nearly $3 million for sick and wounded soldiers by offering entertainment, food, and exhibits and products from the region. When Lincoln addressed the crowd that day, he praised the women who had been the chief organizers of the fairs, saying:

Of all that has been said by orators and poets since the creation of the world in praise of women applied to the women of America, it would not do them justice for their conduct during this war.

By the last year of the war there were 204 Union general hospitals with beds for 136,894 patients. This proved to be the maximum. In February 1865 the United States began closing down its hospitals. Although the Commission had officially disbanded in May 1864, branches in many areas continued to support soldiers and their families for years after the war.

Changing Roles of Women

Although the Sanitary Commission was formed as a civilian organization to provide supplies and aid to the Union Army, the story of the USSC is not just an account of an important institution, but also a history of the changing role of women. While the story is often told through the experiences of a few prominent women, thousands of women worked in the background, receiving no compensation and little recognition.

Women’s work with the USSC also gave women the tools and experience they needed to change their place in society. They learned the importance of a large, national base to lobby for change. Many women had worked in local social reform movements before the war, but the USSC enabled them to begin negotiating with the male-dominated political system.

Clara Barton later claimed that when the Civil War ended:

Woman was at least fifty years in advance of the normal position which continued peace would have assigned her.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Women in the USSC

Caring for the Men: The History of Civil War Medicine

Lincoln’s Fifth Wheel: The Political History of the United States Sanitary Commission

The Union’s Other Army: The Women of the United States Sanitary Commission – PDF