Indian Captive in Minnesota

Wakefield was one of over 100 white women and children who were captured along the Minnesota River in the Dakota War in the late summer and early fall of 1862. Wakefield spent six weeks living among the Mdewakanton Dakota, often in danger from those who felt captives should be killed, but a brave named Chaska intervened on her behalf.

Wakefield was one of over 100 white women and children who were captured along the Minnesota River in the Dakota War in the late summer and early fall of 1862. Wakefield spent six weeks living among the Mdewakanton Dakota, often in danger from those who felt captives should be killed, but a brave named Chaska intervened on her behalf.

The Dakota War

In the years prior to the Civil War, relations between the Dakota people and white settlers had deteriorated considerably. The Dakota had been pushed into a narrow strip of reservation land along the Minnesota River. Once the Civil War began, already scarce resources were further strained, and the supplies promised to the Dakota in a “a series of broken peace treaties” were no longer available.

Therefore, the Indians were starving because food that was promised to them by the government never arrived. One of the tactics the Indians used was to capture white women to get money or food in return. The Dakota War exploded when the despair and anger of the starving tribesmen turned into deadly attacks on settlers in August and September 1862. It took the lives of some 500 whites and an unknown number of Indians.

At the onset of the Dakota War, Sarah Wakefield was the 33-year-old wife of a prosperous Indian Agency doctor in Minnesota. Her husband decided that she and their children would be safer at Fort Ridgely. George Gleason, a clerk at the Lower Agency warehouse, was assigned to drive Wakefield and her children: infant Lucy and 4-year-old James.

Chaska

Their journey to the fort was interrupted by a small band of Dakota, including a brave named Chaska, who captured Wakefield and her children and their driver Gleason. Another brave named Hapa killed Gleason and then turned his gun on Wakefield. Chaska persuaded Hapa to spare Wakefield, and she was taken as a war captive.

Wakefield was still nursing her daughter, and her body was weak and unaccustomed to the outdoors. Throughout her firsthand account of her captivity, Wakefield describes various ways that Chaska and his family protected her from murder, starvation and, at one point, from sexual assault.

Wakefield spent six weeks living among the Mdewakanton Dakota, under constant threats from either Hapa or Little Crow (the great war chief). According to Wakefield, Chaska saved them from certain death and abuse at the hands of his fellow tribesmen. “If it had not been for Chaska,’ Wakefield said, ‘my bones would now be bleaching on the prairie, and my children with Little Crow.”

During her captivity Wakefield observed the ways of her captors and later explained their good reasons for having risen in revolt. She wrote, “People blame me for having sympathy for these creatures, but I take this view of the case: Suppose the same number of whites were living in sight of food, purchased with their own money, and their children dying of starvation, how long do you think they would remain quiet?”

When he felt it was safe, Chaska brought Wakefield and her children to General Henry Sibley and his troops. Wakefield sought to speak out for Chaska’s good deeds. She maintained that Chaska had been her protector and had not killed George Gleason, but Sibley ignored her account.

Death Sentences

After the 269 white captives were freed, more than 400 Dakota and ‘mixed blood’ men were detained by General Henry Sibley, and Chaska was among them. There were 392 trials held for alleged war crimes committed by the Dakota during the war. Sarah Wakefield testified that Chaska protected her and her children after they were taken captive. Three hundred and three Dakota men were sentenced to hang, and their families were brought to a prison camp near Fort Snelling.

President Abraham Lincoln reviewed the cases and pardoned 265 of the 303 condemned men, cutting the list to 39. The president wrote to state leaders that he was “anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak… nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty.”

Chaska’s name was on the presidential pardon list, but (because of an apparent case of mistaken identity) he was hanged. According to the New York Times, Chaska’s case was No. 3 and not listed in the execution order handwritten by Lincoln. Case No. 121, identified by Lincoln as Chaskadon, who had been convicted of shooting and cutting open a pregnant woman, was on the execution list.

However, on December 26, 1862, Chaska was hanged at Mankato, along with the other Dakota men who had been sentenced to death. Innocent of the charges against him, Chaska was hanged instead of Chaskadon. Experts now agree he was mistakenly executed. An act of Congress then banished thousands of Dakota from Minnesota.

Wakefield’s Protest

Sarah Wakefield was horrified when she read a newspaper account two days after the execution and found Chaska’s name among those who were hanged. She demanded an explanation from Reverend Stephen Riggs, who had assisted in transferring the prisoners to the gallows. Riggs had earlier pressured Wakefield to testify that she had been raped during her captivity, but she would not lie.

This is Reverend Stephen Riggs’ explanation of the mistake in the letter he wrote to Sarah Wakefield after the execution:

Mrs. Wakefield, Dear Madam:

In regard to the mistake by which Chaska was hanged instead of another, I doubt whether I can satisfactorily explain it. We all felt a solemn responsibility and a fear that some mistake should occur. We had forgotten that he was condemned under the name of We-chan-hpe-wash-tay-do-pe. We knew he was called Chaska in the prison and had forgotten that any other except Robert Hopkins, who lived by Dr. Williamson, was so called. We never thought of the third one; so when the name of Chaska was called in the prison on that fatal morning, your protector answered to it and walked out. I do not think anyone was to blame. We all regretted the mistake very much.S. R. Riggs.

However, Riggs’ story was not easily believable. He and the clergy and soldiers who gathered the prisoners together the morning of the execution had come to know the Dakota men very well during their imprisonment of many months, and they especially knew Chaska.

Wakefield came to believe that Chaska had been deliberately executed, in retaliation for her testimony and in reaction to rumors that she and Chaska were lovers. General Sibley, who appointed the tribunal that convicted Chaska, privately referred to him as Wakefield’s ‘dusky paramour,’ though she had assured Sibley there had been no sexual relations between them.

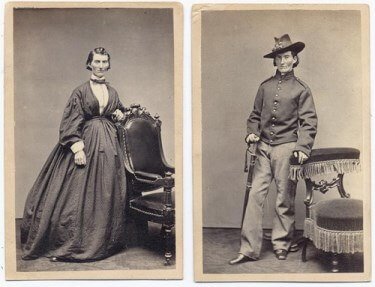

As a final cry for justice, Sarah Wakefield wrote a captivity narrative titled Six Weeks in the Sioux Tepees partly to clear Chaska’s name and her own (because of the rumor that they were lovers) and partly to explain her sympathy for the Dakota people. Throughout her narrative, she challenges not only her role as a submissive woman, but also the government-endorsed, or accepted, version of the Dakota War. This is an excerpt:

Now I will never believe that all in authority at Mankato had “forgotten” what Chaska was condemned for, and I am sure, in my own mind, it was done intentionally. I dare not say by whom, but there is One who knoweth every secret, either good or bad, and the time will come when he will meet that murdered man, and then he will find the poor Indian’s place is far better than his own.

SOURCES

Sarah F. Wakefield

His Thunder, Wakinyatawa Chaska

Wikipedia: We-Chank-Wash-ta-don-pee

My DAD: James Wakefield Gigrich

James is from Minnesota,He had one son James S Gigrich. They live a righteous life .