Civilian Women Protest During the Civil War

In the western Piedmont of North Carolina, residents of the town of Salisbury and Rowan County developed a work ethic and political values that were consciously in opposition to the perceived life of leisure practiced by the eastern planter class. Westerners valued hard labor and self-sufficiency. In the predominantly yeoman countryside, this self-reliant attitude meant that the bulk of labor was done not by slaves but by family members.

In the western Piedmont of North Carolina, residents of the town of Salisbury and Rowan County developed a work ethic and political values that were consciously in opposition to the perceived life of leisure practiced by the eastern planter class. Westerners valued hard labor and self-sufficiency. In the predominantly yeoman countryside, this self-reliant attitude meant that the bulk of labor was done not by slaves but by family members.

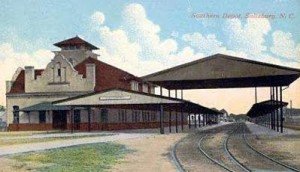

Image: Salisbury Train Depot

Rowan County nurtured small farms that grew subsistence crops – wheat, corn, tobacco and vegetables. Industry complemented agriculture; wealthy planters operated grain mills for profit, while hundreds of British immigrants mined Rowan’s gold fields at the ramshackle settlement of Gold Hill. A warden of the poor operated in Rowan, but social stigma limited his reach to only the most destitute.

After North Carolina seceded from the Union on May 20, 1861, Rowan County supported the Confederacy by sending men to the military while its citizens contributed food and money. Volunteers for the Confederate army from Salisbury and surrounding Rowan County at the beginning of the war were by and large young, unmarried men. The loss of young and independent men was not critical to Rowan County’s pool of labor or its ability to sustain commercial activity.

In 1862 the demand for fresh troops brought about the increasing enlistment of older men with wives and children. Most of these soldiers came from nonslaveholding families. In a county such as Rowan, with a large number of small farms, the absence of a husband was a serious economic loss. When they left for the war, their wives became the sole providers for their families and the caretakers of their farms.

Women plowed, planted and harvested crops, slaughtered livestock and cured meat, all the while maintaining households and raising children. Husbands regularly wrote home advising when and what to plant, the best time for harvest and prices to ask for surplus goods. But a soldier’s low pay, only $11 a month, provided little of what was needed at home.

Southern culture emphasized women’s place as matrons and nurturers within the home and forbade any public and political activity. With the war, however, women were expected to maintain feminine roles while lacking the money, food and protection usually provided by men. Confronted by poverty and starvation, Southern women faced a crisis. Taxation, conscription and impressment left them powerless to provide for their families.

The failure of the county’s attempt to provide for soldiers’ families also contributed to the hardship. Since a portion of Rowan’s 1861 volunteers did include married and with dependent children, the county court had taken action to provide some assistance. How the money was distributed is not known, but cash designated as civilian relief was not used specifically to buy food and supplies; it was given directly to any head of a household who applied. Many families never received any funds.

The soldiers at the front also suffered hardships, and many succumbed to disease. The winter of 1861-62 witnessed 109 deaths of Rowan County men from disease. Meanwhile, Rowan County men were becoming increasingly involved in combat. The fighting around Richmond during the spring and summer of 1862 claimed the lives of sixty-six local soldiers, and fifteen more died at the autumn Battle of Antietam. Fredericksburg and other actions that year in Virginia claimed another twenty-eight men. In the campaigns of 1862 Rowan County lost 228 men, and ninety-nine men were wounded and sixteen captured.

A deceased soldier’s bounty and back pay represented another potential source of support for his family. Soldiers often received bounty money upon enlistment from the county, the state and the Confederate government that could amount to several hundred dollars. With proof of a son’s or a husband’s death, the next of kin traveled to the courthouse to place a claim on any uncollected money. At least fifty mothers, wives and sisters of Rowan County’s dead soldiers placed claims during the autumn and winter of 1862.

In some cases needy women could also rely on traditional sources of community support. The Reverend Samuel Rothrock, pastor of the Organ Church and exempt from service, frequently traveled to the army to deliver letters and packages and returned with the bodies of Rowan’s dead soldiers. Rothrock recorded in his diary on numerous occasions that he aided widows with their applications for provisions, brought in their hay and made shoes for his barefooted parishioners.

By early 1863, a general sense of lawlessness and despair spread through the countryside. Robbery of food and household items, condemned as common thievery in early 1862, were recognized as the increasingly bold acts of a desperate populace by 1863.

Other factors contributed to hardships on the home front. By 1863, most North Carolinians began to feel the effects of the Union blockade, which prevented food and goods from entering the port at Wilmington. Confederate agents went to farms across the state, taking crops and meat for the army’s use, and the Union army raided farms and houses, stealing crops and goods and killing livestock.

With increasing shortages and the growing worthlessness of Confederate currency, inflation and speculation added to the problems. Some merchants hoarded supplies for their own use, and almost all charged exorbitant prices for the surplus. Women and children could make do without many goods and were proud of their sacrifices for the war effort, but they could not do without increasingly expensive food staples.

The Riot

On March 18, 1863, the streets of Salisbury, North Carolina, were invaded by a group of local women, identified only as wives and mothers of Confederate soldiers. The women believed that local merchants had been profiteering by raising the prices of necessary foods and demanded that the merchants sell these goods at government prices, about one-half the market value. When the merchants refused, the women, wielding hatchets, broke down a shop door and threatened other storekeepers who offered resistance.

After collecting 13 barrels of flour, 1 barrel of molasses, 2 sacks of salt and twenty dollars in cash, the women moved on to the North Carolina Railroad Depot, where the Confederate government had established a small quartermaster station to store supplies and equipment before delivery to the army. There they took 10 more barrels of flour.

A reporter for Salisbury’s newspaper, The Carolina Watchman, wrote on March 23, 1863:

Salisbury has witnessed to-day one of the gayest and liveliest scenes of the age. About 12 o’clock, a rumor was afloat that the wives of several soldiers now in the war intended to make a dash on some flour and other necessities of life, belonging to certain gentlemen, who the ladies termed ‘speculators.’

They alleged that they were entirely out of provisions, and unable to give the enormous prices now asked, but were willing to give Government prices. Accordingly, about 2 o’clock they met, some 50 or 75 in number, with axes and hatchets, and proceeded to the depot of the North Carolina Central Road, to impress some there, but were very politely met by the agent, Mr.__ “What on earth is the matter?” The excited women said they were in search of flour which they had learned had been stored there by a certain speculator.

Finally… they returned to the depot… and again demanded the agent that they be allowed to go in. He still refused, but finally agreed to let two go in and examine the flour, and see if his statement was not correct. A restlessness pervaded the whole body, and but a few moments elapsed before a female voice was heard saying: “Let’s go in.”

The agent remarked: “Ladies… it is useless to attempt it, unless you go in over my dead body.” A rush was made, and they went in, and the last I saw of the agent, he was sitting on a log blowing like a March wind. They took ten barrels, and rolled them out and were setting on them, when I left, waiting for a wagon to haul them away.

The ‘Female Raid’ concluded the following morning, according to The Carolina Watchman, when the women met to divide their plunder. The women who participated in the incident were never arrested or charged with a crime, which indicated their neighbors understood and sympathized.

And The Carolina Watchman criticized the county commissioners who failed to provide adequate help for the soldiers’ families, not the women. They should, the article said, “go, all blushing with shame for the scene enacted in our streets on Wednesday last.” After the riot, the county slightly increased the allotment of cash and salt to the needy and improved distribution.

SOURCES

Salisbury Bread Riot

North Carolina and the Civil War

March 1863: The Salisbury Bread Riot