Successful Businesswoman and Humanitarian

Mary Ellen Pleasant was a civil rights activist and entrepreneur who used her fortune to further the abolitionist movement. She worked on the Underground Railroad in several states, including California during the Gold Rush and won significant civil rights in the courts, earning the name ‘Mother of Civil Rights in California.’

Mary Ellen Pleasant was a civil rights activist and entrepreneur who used her fortune to further the abolitionist movement. She worked on the Underground Railroad in several states, including California during the Gold Rush and won significant civil rights in the courts, earning the name ‘Mother of Civil Rights in California.’

Mary Ellen Pleasant altered and embellished her story in several memoirs to offset the criticisms levied against her toward the end of her life, making it difficult to separate fact from fiction. By her own account she was born Mary Ellen Williams on August 19, 1814, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to an African American mother and Louis Alexander Williams, a well educated merchant from the Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii).

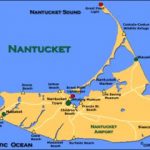

Whatever the case, it is agreed that when Mary was a young girl, her father sent her to live with the Husseys, a Quaker family on the island of Nantucket, Massachusetts, for whom she worked as a clerk at the family store. There she learned the rudiments of running a prosperous business from Grandma Mary Hussey, and witnessed the models of entrepreneurship in Nantucket’s black community.

Mary became smart and witty, and grew to love her Quaker guardians, and the Husseys reveal in their letters that they grew to love her too. Although she could not read or write then, Mary stated in her final memoir, “I could recall the accounts of a whole day, and she [Grandma Hussey] would set them down and they would be right as I remembered ’em.”

As was the case with many Quakers, the Husseys were deeply involved in the abolitionist movement. Through Mary Hussey’s granddaughter, Phoebe Gardner, Mary was later initiated into the circle of the island’s Anti-Slavery Society, making the acquaintance of Anna Gardner – teacher of black children and an ardent abolitionist.

Marriage and Slave Stealing

In the 1840s, the Husseys helped the talented young Mary become a tailor’s assistant in Boston, where she soon met and married James Smith, a wealthy mulatto contractor and merchant from Cuba. After they married, Mary Smith became involved in the Boston abolitionist movement, where the leaders included William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips and Maria Weston Chapman.

According to a letter fragment written by Mary, James passed for white and served as a contributor to William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist paper, The Liberator, and as a rescuer on the Underground Railroad: a series of homes and volunteers who helped slaves escape to freedom. Soon both Smiths were sending fugitives on their way by various routes to Canada, Nova Scotia and Mexico.

Her husband’s death in 1848 left Mary a significant inheritance worth $45,000. An article in the Oakland Tribune stated that Smith had been instructed by her husband to apply this money toward the abolitionist cause, but it appears that she may have retained a significant portion of it for her own plans. However, she remained involved in the fight against slavery for the next several years.

Mary soon began a partnership (possibly a marriage) with John James Pleasants, Pleasance or Plaissance – a former slave who had worked for James Smith as an overseer – but Mary took the name Pleasant. The two continued Smith’s work for a few more years. Mary stated that she disguised herself as a jockey so that she could steal onto plantations and “steal” slaves.

Mary soon became a much-hunted slave rescuer, and increasing attention from slavers forced a move to New Orleans. J.J. Pleasants appears to have been a close relative of Marie Laveau‘s husband, and there is some indication that Mary and Laveau – the Voodoo Queen of New Orleans – met and consulted many times. When she was hunted again for her slave rescue work, Mary fled to California.

In San Francisco

Mary Ellen Pleasant moved to San Francisco around 1852. There she worked as a cook and housekeeper and invested her earnings in stock and money markets. She also lent money to miners and other businessmen at 10 percent interest. Pleasant gained many insights from rich businessmen at the dinners over which she presided, and became a skilled investor.

Pleasant’s tact regarding the secrecy of prominent men, for whom she often procured the services of mistresses, may have helped her win their confidence and their help in her financial planning. She launched a series of businesses catering to the Gold Rush boom – beginning with a string of laundries in the 1850s and diversifying to boarding houses in the 1860s, property investments, matchmaking and mining enterprises.

Although Pleasant always claimed that she provided financial assistance to abolitionist John Brown for his raid on the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859, this contribution has never been verified. Also, after Pleasant moved to California, her second husband no longer appeared in reports about her life. His involvement in her life until his death in 1877, remains unclear.

Pleasant became a philanthropist, using her money bring escaped slaves to San Francisco and get them started in new homes and jobs. She came to the aid of free blacks who had been enslaved illegally in California – a free state since 1850 – by hiding them in her home or in the homes of wealthy whites. She came to the aid of young women, both black and white, who were easy prey for exploitative men in the rough climate of frontier San Francisco.

In addition to helping individual blacks overcome oppression, Pleasant promoted the cause of civil rights in California in two key court decisions. In 1863, she was involved in a case that earned blacks the right to have their testimonies heard in California courts. In 1866 she organized a sit-in of San Francisco streetcars because blacks were denied passage.

In the Reconstruction era, she helped end racial discrimination in California streetcars by suing a San Francisco streetcar company for continuing to deny service to African Americans. The North Beach and Mission Railroad Company was forced to pay Pleasant $500 in damages, and this decision by a lower court was upheld by the California State Supreme Court in 1868.

A tough capitalist with abolitionist zeal, an entrepreneur and a revolutionary, Mary Ellen Pleasant defied the mores of her time to become a leading figure in the struggle for equal rights. Rumors that her boarding houses were fronts for providing well-to-do men with mistresses abounded, but the charges were never proven. Her establishments were noted for being a cut above the crass dance halls and lewd “houses of joy” that formed the mainstay of evening entertainment in San Francisco at that time.

The Bell Affair

Controversy over Pleasant’s life was heightened more or less permanently after she became housekeeper for Thomas Bell, a wealthy businessman of Scottish descent. Pleasant had met Bell at one of her boarding houses, and later moved with Bell and his wife Teresa into a 30-room mansion that Pleasant had supposedly designed. Mary was cast in the role of everything from Bell’s lover to a cunning thief who extorted significant sums from the Bell fortune.

Pleasant did seem to have control over the finances of the Bells that far exceeded the typical boundaries of a housekeeper. Her name was on the deed to the Bell homestead, and some newspaper reports indicated that Pleasant stole money out of the family coffers. She may have used some of the money she secured from the estate to help the plights of blacks. However, other reports maintained that her “charity” was directed toward her own financial gain.

After Thomas Bell fell to his death from an upper-floor window, suspicions about Pleasant having murdered him arose. These suspicions died down when Bell’s will left no money or property to her. Troubles arose for Pleasant years later, however, when Bell’s widow, whose relationship with Pleasant had deteriorated, turned on her. Teresa Bell began asserting that Pleasant had pushed her husband out of the window, which resulted in a barrage of ill feeling toward Pleasant in San Francisco.

In another case that made headlines in the late nineteenth century, Pleasant supported the cause of Sarah Althea Hill’s suit against Senator William Sharon of Nevada for breach of a marriage contract. Pleasant provided $5,000 for Hill’s defense against Sharon, supporting the claim that Hill had been Sharon’s mistress. Sharon denied the existence of a marriage contract, and although Hill won her suit at the state level, the decision was overturned by a federal judge who claimed that the contract was a forgery.

Late Years

Although never convicted of Thomas Bell’s murder, Pleasant was forced at age 85 to move out of the Bell estate, despite her assertion that the Bell property really belonged to her. Claiming to be drained financially by her legal entanglements, Pleasant declared bankruptcy in 1899, but the Oakland Tribune estimated that she was worth from $35,000 to $150,000 at the time. Litigation involving the Bell estate continued well beyond Pleasant’s death.

Despite being lambasted in the press over the Bell affair, Pleasant was deluged by get-well cards and flowers by her fellow San Franciscans when she became seriously ill near the end of her life. The San Francisco Examiner reported that “her deeds of charity are as numerous as the grey hairs on her proud old head.”

Mary Ellen Pleasant died of old age in San Francisco on January 4, 1904 in poverty. She had been befriended by Olive Sherwood near the end of her life, and was buried in the Sherwood family plot located at Tulocay Cemetery in Napa, California. Her gravesite is marked with a metal sculpture that was dedicated on June 11, 2011.

I dislike writing about women whose history cannot be verified. However, what is clear from many sources is that Mary Ellen Pleasant was a very shrewd woman who rose from modest circumstances to a position of significant impact in San Francisco society. Also well established is her active support of important civil rights causes. For those reasons alone, her story must be told.

In 1976, Memorial Park in San Francisco was established in Pleasant’s memory at the site of the Pleasant/Bell mansion by the African American Historical and Cultural Society. Few women, black or white, made such an impact on both real life and the imaginations of San Francisco during its formative years in the late nineteenth century.

SOURCES

Mary Ellen Pleasant

Wikipedia: Mary Ellen Pleasant

Gale Contemporary Black Biography: Mary Ellen Pleasant

Aloha!

I’m glad that people are paying attention an an important woman of San Francisco (I, myself, have generational ties to the area!). I only have one suggestion, however. Please consider changing the image identified as “Mary Ellen Pleasant.” That is actually an image of Queen Emma of Hawaiʻi. Many images of our Queen have been misidentified as Mary Ellen Pleasant, and so to honor both women, it would be good to correct these mistakes. You can find information about the project to correct the errors at https://www.patreon.com/posts/68911778

Thank you so much for your time,

Leilehua Yuen

Interesting how given US historical narratives US historical narratives regarding blacks and especially black women, that the author seems to say that Ms. Pleasants accounts can’t be verified. From various accounts this woman had her own during her life and it was ‘stolen/finessed’ by the Bells.

I’d also like the author of this blog to help to correct the historical record and correctly identify the woman in this photo as Queen Emma of the Kingdom of Hawai’i. Both women were photographed by the same studio in San Francisco. At some point a story was written about Mary Ellen Pleasant was written and the photo of Queen Emma was used, and history has been altered ever since.