Abolitionist and Women’s Rights Activist

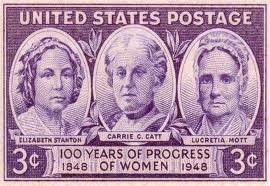

Martha Wright was a feminist and abolitionist in the Civil War Era, and sister of women’s rights leader Lucretia Mott. In July 1848, while Mott was visiting Martha’s home in Auburn, New York, the sisters met with Elizabeth Cady Stanton in nearby Seneca Falls to discuss the need for greater rights for women. Within a few weeks, they held the First Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls.

Martha Wright was a feminist and abolitionist in the Civil War Era, and sister of women’s rights leader Lucretia Mott. In July 1848, while Mott was visiting Martha’s home in Auburn, New York, the sisters met with Elizabeth Cady Stanton in nearby Seneca Falls to discuss the need for greater rights for women. Within a few weeks, they held the First Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls.

Image: Public relations portrait of Wright that was used in the

book, History of Woman Suffrage, by Susan B. Anthony

and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Volume I, published in 1881.

Martha Coffin was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 25, 1806, the youngest of eight children born to Quakers Thomas and Anna Folger Coffin. Martha’s father was a merchant and former Nantucket ship captain. The family moved to Philadelphia when Martha was three.

Martha’s father died in debt in 1815, and her mother paid off his creditors and supported the family by running a boardinghouse and a small shop. With a strong female role model in her mother and the Quaker tenets of individualism, pacifism, equality of the sexes and opposition to slavery, young Martha was well prepared for her future role as an abolitionist and women’s rights advocate.

Martha attended a Philadelphia day school and eventually transferred to a Quaker boarding school outside the city. In 1822, Peter Pelham, a wounded War of 1812 veteran from Kentucky, came to Philadelphia for medical care and boarded at the Coffin home. Sixteen-year-old Martha and Peter, then 37, fell in love and wished to marry but Peter was not a Quaker and Martha’s mother refused to give consent.

Peter left for a Florida military post, but maintained correspondence during his time away. Upon his return to Philadelphia in 1824, Anna Coffin finally gave consent for the couple to marry. The Quaker community, however, refused to accept the marriage.

Martha married Peter Pelham in 1824 and moved with him to a frontier fort at Tampa Bay, Florida. Martha was expelled from the Quakers for marrying outside the faith, an event that contributed to her lifelong estrangement from organized religion.

The following year Martha gave birth to a daughter, but Peter died in 1826, leaving Martha a nineteen-year-old widow with an infant child. To support herself and her daughter Marianna, Martha joined her mother in Aurora, New York, where she taught painting and writing at a Quaker girls’ school.

In 1829, Martha met and married a young law student named David Wright, with whom she would have six more children. As David’s law practice grew, the family moved to nearby Auburn, New York.

With her sister Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha attended the founding meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia in 1833. With the support of her husband, Wright thus began her forty plus years of dedication and commitment to women’s rights and the abolition of slavery.

Seneca Falls Convention

Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton had become friends in the spring of 1840 when they met at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, England, where Stanton’s husband was a delegate. The male delegates attending the convention voted that women should be denied participation in the meetings, even if they, like Mott, had been nominated to serve as official delegates of their respective abolitionist societies.

After considerable debate, the women were required to sit in a roped-off section hidden from the view of the men in attendance. They were soon joined by prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who arrived after the vote had been taken and, in protest of the outcome, refused his seat, electing instead to sit with the women.

Denied her seat at the convention, as were all the women delegates, Mott discussed with Stanton the need for a convention on women’s rights. The plan came to fruition in July 1848, when Mott visited Martha’s home in Auburn, New York. During that visit, the sisters met with Stanton and two other women and decided to hold a convention in nearby Seneca Falls, New York (where Stanton lived), to discuss the need for greater rights for women.

On July 19, 1848, the first day of the Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention, Lucretia and Martha arrived by train from Auburn. The meeting spanned two days and six sessions, and included a lecture on law and multiple discussions about the role of women in society. On the morning of the first day of convention, the organizing committee arrived at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel shortly before ten o’clock.

Though the first session had been announced as being exclusively for women, some young children of both sexes had been brought by their mothers, and about 40 men were there expecting to attend. The men were not turned away, but were asked to remain silent.

Starting at 11 o’clock, Elizabeth Cady Stanton spoke first, exhorting each woman in the audience to accept responsibility for her own life. Stanton read the Declaration of Sentiments, which was based on the language and content of the Declaration of Independence. Stating that “all men and women are created equal,” they demanded equal rights for women, including the right to vote.

It was first read in its entirety, then re-read each paragraph so that it could be discussed at length, and changes incorporated.

At the afternoon session on the first day, Lucretia read a humorous article from a newspaper, written by Martha, in which Wright questioned why, after an overworked mother completed the myriad daily tasks that were required of her but not of her husband, she was the one upon whom written advice was “so lavishly bestowed.”

Martha was six months pregnant with her seventh child, testimony that the bearing of children does not preclude women from making important public contributions to society. She and Lucretia accepted an invitation from Stanton to stay the night at her house before attending the second day’s session.

On Thursday, July 20, 1848, at the morning session the question of whether to allow men signatures was solved by having two sections of signatures, one for women followed by one for men. Of the 300 present 68 women signed the Declaration of Sentiments, along with 32 men.

The convention was seen by some of its contemporaries, including Mott, as but a single step in the continuing effort by women to gain for themselves a greater proportion of social, civil and moral rights, but it was viewed by others as a revolutionary beginning to the struggle by women for complete equality with men.

This first convention marked the formal beginning of the women’s rights movement in America. At the time women were not allowed the freedoms assigned to men in the eyes of the law, the church or the government. Women did not vote, hold elective office, attend college or earn a living. If married, they could not make legal contracts, divorce an abusive husband, or gain custody of their children.

Two weeks later a Woman’s Rights Convention was held in Rochester, New York on August 2. It was followed by state and local conventions in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York. The first National Woman’s Rights Convention was held in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1850.

Martha Wright participated in many state and national conventions in various capacities. She was secretary at the 1852 and 1856 National Women’s Rights Conventions, served as an officer at the 1853 and 1854 National Women’s Rights Conventions and presided over the National Women’s Rights Convention in 1855 in Ohio and the New York State Women’s Rights Convention held in Saratoga that year. Her sister Lucretia was frequently the keynote speaker.

In the antebellum years, Martha Wright was also an ardent abolitionist and ran her home in Auburn as a station on the Underground Railroad, frequently allowing fugitive slaves to sleep in her kitchen. She became a close friend and supporter of Harriet Tubman, who obtained property in Auburn shortly before the Civil War.

In a letter to her sister on December 30, 1860, Martha wrote:

We have been expending our sympathies, as well as congratulations, on seven newly arrived slaves that Harriet Tubman has just pioneered safely from the Southern Part of Maryland. One woman carried a baby all the way and brought two other children that Harriet and the men helped along. They brought a piece of old comfort and a blanket in a basket with a little kindling, a little bread for the baby with some laudanum to keep it from crying during the day.

They walked all night carrying the little ones, and spread the old comfort on the frozen ground, in some dense thicket where they all hid, while Harriet went out foraging, and sometimes could not get back till dark, fearing she would be followed. Then, if they had crept further in, and she couldn’t find them, she would whistle, or sing certain hymns and they would answer

Martha’s correspondence with slaveholding relatives of her first husband grew increasingly contentious with the approach of the Civil War. One of her nephews became a hero of the Confederacy at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Her son William served in the Union artillery and was seriously wounded at Gettysburg while repelling Pickett’s Charge.

Martha presided over numerous antislavery meetings, including two in upstate New York that were disrupted by angry anti-abolitionist mobs. In 1863, Martha and other women’s rights workers formed the Women’s National Loyal League, and carried petitions for the abolition of slavery, which was finally achieved in 1865 with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.

The women’s right movement grew into a cohesive network of individuals who were committed to changing society. Martha was instrumental in the formation of the American Equal Rights Association, which attempted to merge the issues of black suffrage and woman suffrage. However, controversy arose over the Fifteenth Amendment, which provided the right to vote only to black males.

This issue split the postwar women’s movement into two camps, one led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, the other by Lucy Stone. Martha sided with her friends Stanton and Anthony, and in 1874 was elected President of their National Woman Suffrage Association. Minutes from the 1874 NWSA meeting in New York City read in part, “Martha C. Wright, one of the most judicious and clear-sighted women in the movement.”

Martha’s youngest daughter Ellen had married William Lloyd Garrison, Jr., son and namesake of the abolitionist leader. In December 1874, Martha traveled to Boston to assist the Garrisons at the birth of her fourteenth grandchild, William Lloyd Garrison III. Martha took ill there with typhoid pneumonia.

Martha Wright died in Boston on January 4, 1875, at the age of sixty-eight. She was buried in her son-in-law’s family plot at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, New York. Her daughter Eliza Wright Osborne, also a noted suffragist, and her grandson, prison reformer Thomas Mott Osborne, were later interred there as well.

Susan B. Anthony was shocked at the news of Martha’s death, and wrote in her diary, “I could not believe it; clear-sighted, true and steadfast almost beyond all other women!”

Much of Martha’s correspondence, full of wit, wisdom, and erudition – surprising for someone whose formal education ended at the age of fifteen – has been preserved in the archives of Smith College and Syracuse University. The collection is still used by historians studying reform movements and middle-class family life in nineteenth-century America.

Image: Martha Wright Statue

Image: Martha Wright Statue

Women’s Rights National Historical Park

Seneca Falls, New York

The importance of the Seneca Falls Convention was recognized by Congress in 1980 with the creation of the Women’s Rights National Historical Park at the site. The Park’s Visitor Center today features a group of life-size bronze statues to honor the women and men who in 1848 initiated the organized movement for women’s rights and woman suffrage. Her statue shows her, as she was then, visibly pregnant. In 2005, the park featured a display about the relationship between Lucretia and Martha, and in 2008, featured a display focused on Martha.

In their book, A Very Dangerous Woman: Martha Wright and Women’s Rights (2004), Sherry Penney and James D. Livingston (Martha’s great-great grandson) make good use of Martha’s letters to her family, friends and colleagues, including Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. These letters reveal Wright’s engaging wit and offer an insider’s view of nineteenth-century reform and family life.

Martha Coffin Wright was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York, on October 7, 2007.

SOURCES

Martha C. Wright

Text of H. Res. 588

Wikipedia: Martha Coffin Wright

About.com: Martha Coffin Wright