Wife of Union General George Gordon Meade

In letters home to Margaretta Meade during the Civil War, General George Meade commented frankly on every facet of the war. Two days after the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, he wrote: “The army are in the highest spirits, and of course I am a great man. The most difficult part of my work is acting without correct information on which to predicate action.”

In letters home to Margaretta Meade during the Civil War, General George Meade commented frankly on every facet of the war. Two days after the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, he wrote: “The army are in the highest spirits, and of course I am a great man. The most difficult part of my work is acting without correct information on which to predicate action.”

Early Years

Margaretta Sergeant, born June 26, 1815, was the daughter of Margaretta Watmough Sergeant and the Honorable John Sergeant, Henry Clay’s running mate in the 1832 presidential election.George Gordon Meade was born on December 31, 1815, in Cadiz, Spain, where his father, Richard Worsam Meade, was serving as an agent for the United States Navy. The Meades were a prominent Philadelphia family with international mercantile interests. Mr. Meade ran into financial and legal difficulties there as a result of the Napoleonic Wars (1804-1815), and the family moved back to the United States.

For the next few years, the Meade family moved between Baltimore and Washington, and George attended several different schools. He was attending Mount Hope Institution in Baltimore, Maryland, when he had to withdraw, after his father suffered further financial setbacks.

Though he wanted to attend a regular college, George applied for the US Military Academy at West Point and became a cadet on September 1, 1831, at the age of 16. Despite his lack of enthusiasm for the Academy, he performed well as a student and graduated 19th out of 56 in the class of 1835.

Lieutenant George Meade was appointed to the Third US Artillery, and transferred to Florida at the beginning of the Seminole Wars. He became ill with fever while in Florida, and was reassigned to the Watertown Arsenal in Massachusetts for administrative duties. His term at Watertown helped him recover from his feverish bouts, but he was very disillusioned with the army and prospects of a military career.

Meade had no desire to remain in military life, so he resigned his commission in the army in 1836. He went to work for a railroad company, surveying new territory for rail lines – first for the Alabama/Georgia/Florida Railroad, then on the Mississippi/Texas border.

Marriage and Family

In 1840, he was in Washington, DC, where he met his future wife. On his twenty-fifth birthday – December 31, 1840 – George Meade married Margaretta Sergeant at St. Peter’s Church, in Philadelphia, PA. They would have seven children – four sons and three daughters: John, George, Margaret, Spencer, Sarah, Henrietta, and William

Determined to give his new bride a higher standard of living, Meade re-applied for military service in 1842, and was appointed a Second lieutenant in the Topographical Engineers. In the war with Mexico, he was on the staffs of Generals Zachary Taylor and Robert Patterson, and was brevetted for gallant conduct at Monterey.

Meade’s military assignments took him to Texas in 1845, where he was later assigned to General Winfield Scott’s Army during the War with Mexico. After the conflict in Mexico was over, he was promoted to captain, and for the next ten years spent time in surveying and design work. He was moved to Philadelphia, where he built lighthouses for the Delaware Bay. As captain of topographical engineers, he participated in the survey of the Great Lakes and their tributaries.

Meade in the Civil War

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Captain George Gordon Meade offered his services to Pennsylvania, and was appointed as a brigadier general. Like many American families during the Civil War, Meade’s was also touched personally by sectional strife. Margaretta’s sister was married to Governor Henry Wise of Virginia, who later became a brigadier general in the Confederate army.

Meade was assigned to command a brigade of Pennsylvania volunteers, and it was during this time that he began a friendship with General John Reynolds from Lancaster, Pennsylvania. General Meade and his Pennsylvanians built fortifications near Tenallytown, Maryland. Nicknamed The Old Snapping Turtle, Meade gained a reputation for being short-tempered and obstinate with junior officers and superiors. He especially disliked civilians and newspapermen. He spent the fall and winter of 1861 – 1862 working on the defenses of Washington.

In March 1862, his command was assigned to the Army of the Potomac under General George B. McClellan, on the Peninsula southeast of Richmond. His troops saw hard fighting at the Battles of Mechanicsville and Gaines’ Mill. On June 30, 1862, at the Battle of Glendale, Meade was seriously wounded, when a musket ball struck him above the hip, clipped his liver, and just missed his spine as it passed through his body. Another bullet struck his arm, but the feisty general stuck to his horse and continued to direct his troops. It was only after heavy loss of blood that he was forced to leave the field.

Meade recovered from his wounds in a Philadelphia hospital, but was only partially recovered, when he returned to command on August 26, at the Second Battle of Bull Run, in which he led his brigade, now assigned to the Army of Virginia. His brigade made a heroic stand on Henry House Hill to protect the rear of the retreating Union Army.

Meade recovered from his wounds in a Philadelphia hospital, but was only partially recovered, when he returned to command on August 26, at the Second Battle of Bull Run, in which he led his brigade, now assigned to the Army of Virginia. His brigade made a heroic stand on Henry House Hill to protect the rear of the retreating Union Army.

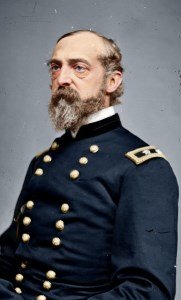

Image: General George Meade

On September 12, Meade received command of the 3rd Division, I Corps, Army of the Potomac, and distinguished himself during the Battle of South Mountain on September 14. When his brigade stormed the heights at South Mountain, General Joseph Hooker, Meade’s corps commander, was heard to exclaim, “Look at Meade! Why, with troops like those, led in that way, I can win anything!”

In the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, Meade replaced the wounded Hooker in temporary command of the I Corps, selected personally by McClellan above other generals who were his superior in rank. He performed well at Antietam, but was wounded in the thigh.

During the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, Meade’s division made the only breakthrough of the Confederate lines, spearheading through a gap in General Stonewall Jackson‘s corps at the southern end of the battlefield. However, his attack was not reinforced, resulting in the loss of much of his division.

After Fredericksburg, Meade received command of the V Corps, which he led in the Battle of Chancellorsville in early May 1863. General Hooker, then commanding the Army of the Potomac, had aggressive plans for the campaign, but was too timid in execution, allowing the Confederates to seize the initiative. Meade’s corps was left in reserve for most of the battle. Though the army had been soundly defeated there, Meade handled his corps with great skill and protected the important fords on the Rappahannock River. Afterwards, Meade argued with Hooker in favor of resuming the attack against Lee, but to no avail.

A Difficult Man

Meade’s love of truth and dedication to duty may help explain an element of his nature that everybody remarked about – his temper. An energetic, exacting man, Meade was well known for his violent impatience with stupidity, negligence, and laziness. He would erupt quickly in outbursts of rage or annoyance, especially under the stress of active campaigning or a pitched battle.

Meade’s short temper earned him notoriety, and while he was respected by most of his peers, he was not well-loved by his army. Some referred to him as “a damned old goggle-eyed snapping turtle. As his aide Theodore Lyman expressed it: “I don’t know any thin old gentleman… who, when he is wrathy, exercises less of Christian charity than my well-beloved chief!”

Though irritable under stress, Meade’s decisions were “always founded in good reason,” and while his manner was hard on people, it did get results. Lyman wrote that Meade was “always stirring up somebody. But by worrying, and flaring out unexpectedly on various officers, he does manage to have things pretty shipshape.”

Though too sparing in his praise of the work of his subordinates – partly out of a reluctance to show his feelings, and partly out of an Old Army sense that total effort was each man’s duty in such times – there were signs of a pleasanter side. When not absorbed with his work, Meade was a different person, telling funny stories with “great fluency and… elegant language,” and on occasion would sit by the campfire “talking familiarly with the aides.”

However, he usually kept himself apart, and made no effort to make himself popular. He made it a rule not to speak to members of the press, and in retaliation journalists agreed among themselves not to mention him in dispatches except in reference to setbacks.

A Family Man

Though it wasn’t evident to his military counterparts, George Meade was tenderly devoted to his wife and children. If he was known as “a damned old goggle-eyed snapping turtle” to his men, his temper never appeared in his letters home.

Here in a letter to his daughter in the spring of 1862:

I think a great deal about you, and all the other dear children. I often picture to myself as I last saw you – yourself, Sarah, and Willie lying in bed, crying, because I had to go away, and while I was scolding you for crying, I felt like crying myself.

It is very hard to be kept away from you, because there is no man on earth that loves his children more dearly than I do, or whose happiness is more dependent on being with his family. Duty, however, requires me to be here, to do the little I can to defend our old flag, and whatever duty requires us to do, we should all, old and young, do cheerfully, however disagreeable it may be.

New Commander of the Army of the Potomac

In mid-June 1863, General Robert E. Lee once again began an invasion of the North, and President Abraham Lincoln urged General Hooker to pursue and defeat him. Hooker’s initial plan was to seize Richmond instead, but Lincoln immediately vetoed that idea, so the Army of the Potomac began to march north, attempting to locate Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia as it slipped down the Shenandoah Valley into Pennsylvania.

Hooker’s mission was first to protect Washington, DC, and Baltimore, and second to intercept and defeat Lee. Unfortunately, Lincoln was losing any remaining confidence he had in Hooker. When the general got into a dispute with Army headquarters over the status of defensive forces in Harper’s Ferry, he impulsively offered his resignation in protest, which was quickly accepted by Lincoln and General-in-chief Henry Halleck.

In the early morning hours of June 28, 1863, a messenger from President Abraham Lincoln woke Meade in his tent and informed him that he was now commander of the Army of the Potomac – and no one was more surprised than Meade. He later wrote to his wife that when the officer entered his tent to wake him, he assumed that Army politics had finally caught up with him, and he was being arrested.

In a letter to his wife, written shortly before this promotion, Meade had analyzed his chances for appointment:

I do not… stand any chance, because I have no friends, political or others, who press or advance my claims or pretensions, and there are so many others who are pressed by influential politicians, that it is folly to think I stand any chance upon mere merit alone. Besides, I have not the vanity to think my capacity so pre-eminent, and I know there are plenty of other equally competent with myself, though their names may not have been so much mentioned.

Meade had not actively sought command and was not the president’s first choice. John Reynolds, one of four major generals who outranked Meade in the Army of the Potomac, had earlier turned down the president’s suggestion that he take over. Meade tried to decline the promotion, but was told that it was impossible – the army was now his, whether he wanted it or not.

Though surprised, Meade realized that he had support from many of the army’s corps commanders, including his old friend Reynolds, who commanded the First Corps. The other three corps commanders who were senior to Meade in rank – Generals Darius Couch, Henry Slocum, and John Sedgwick – all sent word to him that they were willing to serve under his leadership. The army was then concentrated around Frederick, Maryland, and Meade officially assumed command at Prospect Hall in Frederick. The following day, he issued orders to continue the army’s pursuit of General Lee.

Meade at Gettysburg

Having been in command of the army for only three days before Gettysburg, Meade’s style of command, in contrast to Robert E. Lee, was to be actively and directly involved in the events on the battlefield. He had been a division and a corps commander too long and too recently to stand aloof at headquarters, while others moved the army’s huge formations across the landscape, and his nervous energy required that he be mobile. He was constantly in the saddle, issuing orders and seeing that they were obeyed.

In his Gettysburg sketch of Meade, Frank Haskell wrote, “His habitual personal appearance is quite careless, and it would be rather difficult to make him look well dressed.” At Gettysburg, his dress was perfectly in keeping with his personal lack of airs – he wore the familiar dark blue flannel blousewith two-star shoulder straps, field cap, light blue pantaloons tucked into his high-top boots, an officer’s leather belt, and regulation sword. Tall and thin, near-sighted and rather ungainly, at age forty-seven Meade looked considerably older.

A London newspaperman described Meade at Gettysburg:

He is a very remarkable looking man – tall, spare, of a commanding figure in presence, his manner pleasant and easy but having much dignity. His head is partially bald and is small and compact, but the forehead is high. He has the late Duke of Wellington class of nose, and his eyes, which have a serious and almost sad expression, are rather sunken, or appear so from the prominence of the curved nasal appearance. He has a decidedly patrician and distinguished appearance.

July 1

A little after midnight on July 1, 1863, Meade sent out the day’s marching orders for the Army of the Potomac from his headquarters at Taneytown, 12 miles south of Gettysburg. Those orders moved the army forward on a broad front, to prevent Lee from slipping around either flank and threatening Washington or Baltimore. Thinking that Lee slightly outnumbered him, Meade also sent out a second, conditional plan, a defensive fall-back called the Pipe Creek Circular, before he went to bed.

Meade remained at Taneytown on July 1, and his first news from the front came about 11:30 am. This was a message from General John Reynolds at Gettysburg, informing Meade that the Rebels were advancing in strong force, and he (Reynolds) would do everything possible to keep them from seizing ‘the heights beyond the town.’ Meade’s first fear was that Reynolds would fail to hold the town, retreat toward Emmitsburg, and uncover the road to Taneytown, exposing the army’s center.

At 1:00 pm, Meade received word of the death of his friend, General Reynolds. Meade immediately ordered General Winfield Scott Hancock to begin marching the Second Corps from Taneytown toward Gettysburg. Since this involved placing Hancock over two officers who outranked him – Sickles and Howard – Meade gave Hancock written authority and had him on his way to Gettysburg by 1:30 pm. By the end of the first day, two Union infantry corps had been almost destroyed, but had taken up strong positions on favorable ground.

At 6:00 that evening, Meade announced in a telegram to Washington his decision to concentrate the army and fight at Gettysburg. A flurry of orders followed: at 7:00 he ordered Sykes to march the Fifth Corps to Gettysburg, at 7:30 he sent similar orders to Sedgwick and Sickles. Meade’s only negligence on July 1 was in believing Slocum would be governed by events and move his Twelfth Corps forward the short distance to Gettysburg. Meade arranged the movements of the supply train and the artillery reserve during the evening, then headed toward the battlefield at 10:00 pm. with a small party.

The first day at Gettysburg, more significant than simply a prelude to the bloody second and third days, ranks as the twenty-third largest battle of the war by number of troops engaged. About one quarter of Meade’s army (22,000 men) and one third of Lee’s army (27,000) were engaged. Throughout the evening of July 1 and morning of July 2, most of the remaining infantry of both armies arrived on the field.

Meade arrived at Cemetery Hill about 11:30 P.M., greeted the assembled generals, and informed them that the rest of the army was moving up, and that it would fight there. He then made a walking survey of the Union position in the moonlight. Just before dawn, he rode south along the line of Cemetery Ridge, then to Culp’s Hill, making sketches of the terrain and indicating the positions he wished each corps to take. He then established his headquarters in the farmhouse of Lydia Leister, which was centrally located on the Taneytown Road, 800 feet in the rear of Cemetery Hill.

Image: Meade’s Headquarters at Gettysburg

Image: Meade’s Headquarters at Gettysburg

Lydia Leister was a widowed Pennsylvania Dutch woman who lived with her six children in this tiny house, which was taken over by General Meade. This Matthew Brady photograph shows the battle scarred house that lay just over the ridge from the Union lines. The carcasses of Union horse and mules, killed during the battle, are strewn about the road and grounds.

July 2

All morning, there was a flow of orderlies and aides through the farmhouse dashing up with reports and off with orders in preparation for a major battle. Meade, despite his lack of sleep, was alert, and firm and pleasant in his manner. By noon, the corps were all present (except the Sixth Corps, still marching hard) and in their positions, from left to right: Third Corps on the southern half of Cemetery Ridge near Little Round Top, Second Corps on the northern half of Cemetery Ridge, Eleventh Corps on Cemetery Hill with remnants of the First Corps immediately behind in reserve, and Twelfth Corps on Culp’s Hill. The Fifth Corps had just arrived and was resting in the rear near Power’s Hill.

Using the most qualified of his corps commanders to act for him in the field, Meade skillfully deployed his forces for a defensive battle, reacting swiftly to fierce assaults on his line’s left, right, and center. Although he was expecting an attack on his right where the enemy was visible, he had trouble on his left in the form of General Sickles, who in the early afternoon expressed agitation about where he should put his corps.

Around 4:00 in the afternoon, Meade rode to the left to examine Sickles’ position. Here he made the jaw-dropping discovery that Sickles had advanced his line a full mile to the high ground along the Emmitsburg Road. Before any remedy could be considered, the boom of cannon announced the beginning of Longstreet’s attack on Sickles’ exposed line. Sickles would have to stay where he was.

Recognizing Little Round Top, which was uncovered by Sickles’ advance, as the key to the Union left, Meade sent General Gouverneur Warren to investigate the situation. When Warren sent back word that there were no troops there, Meade ordered Sykes to throw his Fifth Corps immediately in that direction. This was the first in a series of improvisations Meade ordered by the Third, Fifth, and Second Corps on the afternoon of July 2.

Meade was near the battle line the whole afternoon, so near that his horse was wounded. At one point, he rode forward with the skirmish line, waving his hat and yelling, “Come on, gentlemen!” He timed his orders for reinforcements precisely; hard-pressed units consistently received support at just the right moments. In the end, CSA General James Longstreet‘s assault was turned back, but at the cost of thirteen brigades battered, some shattered so completely they could not be used again.

At the end of the day, even with his left battered and his right partially in enemy hands, Meade could take satisfaction in the first success the Army of the Potomac had enjoyed against Lee since Malvern Hill a year earlier. From 9:00 that evening until midnight on July 2, Meade met in his cramped headquarters with eleven of his top generals, who echoed Meade’s resolve to stay and fight it out.

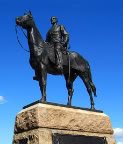

Image: Meade Equestrian Monument on Cemetery Ridge

Image: Meade Equestrian Monument on Cemetery Ridge

Near the Angle, Gettysburg National Military Park

July 3

Meade rose before dawn on July 3. At daybreak, heavy fighting broke out on Culp’s Hill. Meade had confidence in the Twelfth Corps leaders Slocum and Williams, and did not go in person to supervise their conduct of the battle. He sent a fresh Sixth Corps brigade to Culp’s Hill as a reinforcement, and advised Howard on nearby Cemetery Hill to have his men stand by to be ready to move there.

The battle raged all morning until 11:00 am, when the last of the Confederates on the hill had successfully been driven off. Witnesses described Meade as appearing confident, “more the General, less the student” than before, but retained his “quick and nervous” manner. After the fighting ceased on Culp’s Hill, Meade accepted General Gibbon’s invitation for lunch with some of his fellow generals.

When the roar of the 150-gun Confederate cannonade started around 1:00 pm, Meade’s headquarters became a very dangerous place to be. Shells hit the Leister house numerous times. Sixteen horses were killed while tied to the fence rail in the yard. But Meade was reluctant to move, afraid couriers with important news would be unable to locate him if he shifted his headquarters. He briefly rode to Slocum’s headquarters on Power’s Hill, then changed his mind and returned.

The last day of the battle, may have been Meade’s finest hour, when the long ranks of Pickett’s Charge appeared around 3:00 pm and headed toward the Copse of Trees (a small grove) on Cemetery Ridge. The thin blue line on the ridge, outnumbered two to one, beat back this desperate assault – the grandest attack in the history of the war – by themselves.

Meade’s Description of Pickett’s Charge:

The cannonade continued for over two hours, when our guns, in obedience to my orders, failing to make any reply, the enemy ceased firing, and soon his masses of infantry became visible, forming for an assault on our left and left center.

The assault was made with great firmness, directed principally against the point occupied by the Second Corps, and was repelled with equal firmness by the troops of that corps, supported by Doubleday’s division and Stannard’s brigade of the First Corps.

During the assault, both Major General Hancock, commanding the left center, and Brigadier General Gibbon, commanding the Second Corps, were severely wounded. This terminated the battle, the enemy retiring to his lines, leaving the field strewn with his dead and wounded, and numerous prisoners in our hands.

When Meade rode up to the ridgeline on Cemetery Ridge in the swirling smoke and was told the enemy had been turned, he said simply, Thank God. A second later, he made a motion as if to take off his hat and wave it in the air, but he remembered himself, and merely waved his hand and cried, Hurrah. He then spurred his horse and made a triumphal ride along the ridge all the way to Little Round Top.

All eyes were now on Meade to see if he would attempt a war-winning counterattack. He did not. The lateness in the day, the absence of the wounded Hancock, the fatigue of the men, the disorganized command that existed after three days of carnage, and the still-fearsome reputation of General Lee – all militated against a bold move at that hour.

With the failure of Pickett’s Charge, the battle was over – the Union was saved. Meade had won the crucial contest in Pennsylvania and saved the country; he now prudently refused to jeopardize that victory. Behind him, this small town of only 2,400 was left with a total of more than 51,000 casualties. Over 172,000 men and 634 cannon had been positioned in an area encompassing 25 square miles. An estimated 569 tons of ammunition was expended and 5,000 dead horses and other wreckage presented a scene of terrible devastation.

General Meade to Margaretta Sergeant Meade:

HEAD-QUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,

GETTYSBURG, PA.

July 5, 1863.

I hardly know when I last wrote to you, so many and such stirring events have occurred. I think I have written since the battle, but am not sure. It was a grand battle, and is in my judgment a most decided victory, though I did not annihilate or bag the Confederate Army. This morning they retired in great haste into the mountains, leaving their dead unburied and their wounded on the field. They awaited one day, expecting that, flushed with success, I would attack them when they would play their old game of shooting us from behind breastworks – a game we played this time to their entire satisfaction.The men behaved splendidly; I really think they are becoming soldiers. They endured long marches, short rations, and stood one of the most terrific cannonadings [sic] I ever witnessed. Baldy [Meade’s horse] was shot again, and I fear will not get over it. Two horses that George [their son] rode were killed, his own and the black mare. I had no time to think of either George or myself, for at one time things looked a little blue; but I managed to get up reinforcements in time to save the day.

The Aftermath

The armies stared at one another across the bloody fields on July 4. Lee reformed his lines into a defensive position, hoping that Meade would attack. The cautious Union commander, however, decided against the risk, and instead ordered a series of small probing actions that elicited Confederate artillery fire, and Meade decided not to press an attack. By mid-afternoon, the firing at Gettysburg had essentially stopped, and both armies began to collect their remaining wounded and bury some of the dead. Lee’s retreat began on the afternoon of July 4.

Beginning on July 5, General Meade ordered his exhausted army southward. Despite the decisive results of the Gettysburg Campaign, President Lincoln criticized Meade for not aggressively pursuing the Confederates during their retreat. At one point, the Army of Northern Virginia was extremely vulnerable with their backs to the rain-swollen, almost impassable Potomac River, but they were able to erect strong defensive positions before Meade could organize an effective attack.

Lincoln believed that Meade had wasted an opportunity to end the war. Yet the controversy did not diminish the significance of the Union victory at Gettysburg, and President Abraham Lincoln expressed the gratitude of the nation. Meade also received the Thanks of Congress, which commended Meade “… and the officers and soldiers of [the Army of the Potomac], for the skill and heroic valor which at Gettysburg repulsed, defeated, and drove back, broken and dispirited, beyond the Rappahannock, the veteran army of the rebellion.”

In a brief letter to Major General Henry W. Halleck written on July 7, President Lincoln remarked on the two major Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. He continued:

Now, if General Meade can complete his work so gloriously prosecuted thus far, by the literal or substantial destruction of Lee’s army, the rebellion will be over.

Halleck then relayed the contents of Lincoln’s letter to Meade in a telegram. Meade’s feelings were hurt. However, despite repeated pleas from Lincoln and Halleck, which continued over the next week, Meade did not pursue Lee’s army aggressively enough to destroy it before it crossed back over the Potomac River to safety in the South. Lincoln complained to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that, “Our army held the war in the hollow of their hand, and they would not close it!”

Letter from President Lincoln to General Meade:

Executive Mansion,

Washington, July 14, 1863

Major General Meade:

I have just seen your dispatch to General Halleck, asking to be relieved of your command, because of a supposed censure of mine. I am very – very – grateful to you for the magnificent success you gave the cause of the country at Gettysburg; and I am sorry now to be the author of the slightest pain to you. But I was in such deep distress myself that I could not restrain some expression of it. I had been oppressed nearly ever since the battles at Gettysburg, by what appeared to be evidences that yourself, and General Couch, and General Smith, were not seeking a collision with the enemy, but were trying to get him across the river without another battle. What these evidences were, if you please, I hope to tell you at some time, when we shall both feel better.The case, summarily stated is this. You fought and beat the enemy at Gettysburg; and, of course, to say the least, his loss was as great as yours. He retreated; and you did not, as it seemed to me, pressingly pursue him; but a flood in the river detained him, till, by slow degrees, you were again upon him. You had at least twenty thousand veteran troops directly with you, and as many more raw ones within supporting distance, all in addition to those who fought with you at Gettysburg; while it was not possible that he had received a single recruit; and yet you stood and let the flood run down, bridges be built, and the enemy move away at his leisure, without attacking him.

And Couch and Smith! The latter left Carlisle in time, upon all ordinary calculation, to have aided you in the last battle at Gettysburg; but he did not arrive. At the end of more than ten days, I believe twelve, under constant urging, he reached Hagerstown from Carlisle, which is not an inch over fifty five miles, if so much. And Couch’s movement was very little different. Again, my dear general, I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape. He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with our other late successes, have ended the war. As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely.

If you could not safely attack Lee last Monday, how can you possibly do so South of the river, when you can take with you very few more than two thirds of the force you then had in hand? It would be unreasonable to expect, and I do not expect you can now effect much. Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it. I beg you will not consider this a prosecution, or persecution of yourself. As you had learned that I was dissatisfied, I have thought it best to kindly tell you why.

Abraham Lincoln

In the next six months, Meade led the Army through an endless series of skirmishes, later called the Mine Run Campaign, trying to outflank Lee’s position in north central Virginia. Despite the best efforts of corps commanders and their commands, Meade was unable to get around Lee or bring him to a major battle. For the remainder of the fall campaigning season in 1863, Meade was outmaneuvered by Lee and withdrew after fighting minor battles, because of his reluctance to attack entrenched positions. The army went into winter quarters along the Rapidan River on January 28, 1864.

Under Grant

General Ulysses S. Grant was appointed commander of all Union forces that same winter, and he decided to accompany the Army of the Potomac in the opening of the spring campaign. Meade offered to resign, but Grant kept him on. Nevertheless, from that point it was Grant’s army – until Appomattox Court House – and Meade was Grant’s subordinate, although nominally in command of the A.O.P.

As Grant’s Overland Campaign ground on, Meade’s control of the army was curtailed by the presence and directions of his superior officer. Nevertheless, he worked diligently in carrying out Grant’s orders and directives, moving the army where Grant desired, and issuing the orders Grant gave.

Grant successfully urged Meade’s appointment as major general in the regular army (August 18, 1864), eulogizing him as the commander who had successfully met and defeated the best general and the strongest army on the Confederate side.

Meade’s promotion came while the army was embroiled in the Siege of Petersburg, which lasted until April 1865, when Lee ordered the defenses abandoned, and his army retreated to Danville. By Grant’s directive, Meade set his army in motion to corral the Confederate forces, aided by General E.O.C. Ord and his Army of the James. Despite nausea and a high fever, Meade insisted that he continue to command the army in what was to be the final campaign, and accompanied his troops in an army ambulance.

On April 9, 1865, Meade’s headquarters were established several miles outside of Appomattox Court House, near those of General Grant. That afternoon, while Grant and his staff rode to the courthouse, Meade once again took to his ambulance with a headache and fever. When the news of Lee’s surrender arrived, Meade was uncharacteristically elated. Despite his illness, he rode his favorite horse Old Baldy to the front to announce the surrender to the troops.

General Meade’s Farewell Address to the Army of the Potomac:

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC

June 28, 1865

Soldiers: This day, two years, I assumed command of you under the orders of the President of the United States. Today, by virtue of the same authority, this army ceasing to exist, I have to announce my transfer to other duties and my separation from you.It is unnecessary to enumerate here all that has occurred in these two eventful years, from the grand and decisive Battle of Gettysburg, the turning point of the war, to the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. Suffice it to say that history will do you justice, a grateful country will honor the living, cherish and support the disabled, and sincerely mourn the dead.

In parting from you, your commanding general will ever bear in memory your noble devotion to your country, your patience and cheerfulness under all the privations and sacrifices you have been called upon to endure.

Soldiers! having accomplished the work set before us, having vindicated the honor and integrity of our Government and flag, let us return thanks to Almighty God for His blessing in granting us victory and peace; and let us sincerely pray for strength and light to discharge our duties as citizens, as we have endeavored to discharge them as soldiers.

GEO. G. MEADE,

Major General, U.S.A.

After the war, Meade was mustered out of the Volunteer Service, but he continued in the Regular Army as the fourth highest ranking officer in the US army. He commanded the military Division of the Atlantic, headquartered in Philadelphia, where at his request, he could remain with his family in his native city, while overseeing all military affairs.

He was also active in civic affairs in Philadelphia, overseeing charity work and service to veterans, and their widows and orphans. In 1866, he became Commissioner of Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, a post that he held till his death. On January 2, 1868, Meade was called to Atlanta to handle Reconstruction, performing his duties with sensitivity and fairness.

The degree of LL.D. was conferred upon Meade by Harvard University, and his scientific attainments were recognized by the American Philosophical Society and the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences. One of his last acts was on May 31, 1872, when he spoke at the dedication of the monument to the Civil War dead of the 21st Ward in Philadelphia.

Meade lived with his wife and family in Philadelphia until October 31, 1872, when he was struck down by a violent pain in his side. Scientist, inventor, scholar, warrior, diplomat, gentleman of highest virtue, a true patriot and hero of his country developed pneumonia brought on by the lingering effects of his old wound from the Battle of Glendale. He was still serving on active duty with the Army.

Major General George Gordon Meade faded quickly and died at Philadelphia on November 6, 1872, at the age of 57. He was laid to rest with much fanfare in Laurel Hill Cemetery in his beloved Philadelphia. In attendance were the President Ulysses S. Grant and his cabinet, numerous dignitaries from civil and military spheres, ordinary citizens who loved and admired him, as well as the veterans, his old comrades who valued him most.

Image: George and Margaretta Meade Graves

Image: George and Margaretta Meade Graves

Meade’s horse, Old Baldy, was purchased by General Meade in September of 1861 for $150, and was ridden by Meade almost exclusively throughout the war. Meade rode Old Baldy at Gettysburg, when the horse was wounded on July 2 by a ball that entered his stomach after passing through Meade’s trouser leg and within a half inch of his thigh.

Old Baldy again survived, but by August of 1864 and another wound, was considered unfit for service, and Meade sent him back to Philadelphia for a well-deserved retirement. Old Baldy did so well, however, that Meade resumed riding him after the war. Old Baldy marched in the funeral procession as the riderless horse for his beloved master, General Meade, on November 11, 1872, when Meade was laid to rest at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

Baldy was later presented to John Davis, a blacksmith near Jenkintown, PA, who kept him until he became too feeble to get up after lying down, and on December 16, 1882, he was mercifully laid to rest. Baldy was more than 30 years old, and had lived ten years after his gallant master,

Margaretta Sergeant Meade died on January 7, 1886, at age 71.

SOURCES

George Meade

Stone Sentinels

George Gordon Meade

Wikipedia: George Meade

American Civil War Battle

About George Gordon Meade

Haskell’s Account of the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg – Friday July 3, 1863

Address Accepting the Monument of General George Gordon Meade