Wife of Confederate General Basil Duke

Henrietta Hunt Morgan was born on April 2, 1840, to Calvin Cogswell Morgan and Henrietta Hunt Morgan of Lexington, Kentucky. Her brother, John Hunt Morgan, would become a celebrated Confederate cavalry commander. Basil Wilson Duke was born in Scott County, Kentucky, on May 28, 1838, the only child of Nathaniel Duke and his wife, the former Mary Pickett Currie. Duke’s parents died during his childhood: Mary when Basil was eight, and Nathaniel when he was 11.

Henrietta Hunt Morgan was born on April 2, 1840, to Calvin Cogswell Morgan and Henrietta Hunt Morgan of Lexington, Kentucky. Her brother, John Hunt Morgan, would become a celebrated Confederate cavalry commander. Basil Wilson Duke was born in Scott County, Kentucky, on May 28, 1838, the only child of Nathaniel Duke and his wife, the former Mary Pickett Currie. Duke’s parents died during his childhood: Mary when Basil was eight, and Nathaniel when he was 11.

Image: General Basil Duke

Basil Duke attended Georgetown College (1853-1854) and Centre College (1854-1855), before studying law at Lexington, Kentucky’s Transylvania University. After graduating in 1858, he went to St. Louis, Missouri, to practice law. His older cousin, also named Basil Duke, was practicing law there, and there were already a multitude of lawyers in Lexington. Basil was 5 feet 10 inches tall, slightly-built, with a resonant voice.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Duke was still practicing law in Missouri, where he helped in the initial forays for Missouri’s secession from the United States. (Missouri would have both Federal and Confederate governments during the War.)

On January 7, 1861, Basil Duke and four others created Minute Men, a pro-secession organization, in response to the pro-Northern politicians who had been recently elected in St. Louis. Duke quickly becoming the leader, despite being only 23 years old. He formed five companies, and sought to acquire the federal arsenal in St. Louis for the secessionist movement.

Duke made a habit of placing secessionist flags at prominent locations, looking to start fights with pro-Union forces. At one point, he managed to obtain four cannon for the Minute Men to use, only for the cannon to be re-captured by Union soldiers soon afterward.

Henrietta Hunt Morganmarried Basil Duke on June 19, 1861, in Lexington Kentucky. They would have eight children together.

Duke immediately enlisted in the Confederate Army and served as a scout for General William Hardee in Missouri. Making his way back to Kentucky, Duke joined the Lexington Rifles, organized by Henrietta’s brother, John Hunt Morgan, as a private. Due to his scouting experience and talent for organization, Morgan immediately made him a first lieutenant and his second-in-command.

In December 1861, Duke became colonel of the Second Kentucky Cavalry. He was most noted during the war was as second-in-command for John Hunt Morgan. Duke was the principal trainer for mounted combat for Morgan’s Raiders.

At the Battle of Shiloh on April 6, 1862, Duke was shot in the left shoulder by a musket. The bullet exited his right shoulder, barely missing his spine. After this, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel, and a few months later to full colonel.

Except at Shiloh, Morgan’s and Duke’s cavalry operated as guerrillas. Duke developed the tactics that made them the toast of Kentucky and heroes of the South: with a thousand men, or so, they would ride down on lightly defended Union posts in Tennessee and Kentucky, burning railroad bridges, destroying transportation materials, and capturing sorely needed supplies.

Duke developed the fast mobile force that rode to the scene and then dismounted and fought like infantry. They tied down large numbers of Union forces for extended periods of time, and panicked the North every time they struck out for the Ohio River. Those who fought with Morgan largely credited Duke for Morgan’s successes.

During 1862, when General Braxton Bragg was getting ready for his march into Kentucky, Morgan’s cavalry was busy in Tennessee, dispersing and capturing detached Federal garrisons. On August 28, when Bragg crossed the Tennessee River at Chattanooga and pushed northward, General Kirby Smith, who was already in Kentucky, ordered Morgan to join him at Lexington in the blue grass region.

With part of his command, Morgan marched to the mountains of eastern Kentucky, while Colonel Duke with the balance of the command marched to the Ohio River, where they defeated two small steamers and captured the town of Augusta, taking between 300 and 400 prisoners.

On the retreat from Kentucky, Morgan’s command attacked the rear of Union General Don Carlos Buell, capturing hundreds of prisoners and some richly-laden wagon trains. Morgan had entered Kentucky 900 strong. His command when he returned to Tennessee numbered nearly 2000. Almost 1200 prisoners had been taken by the cavalry.

Just before the Battle of Murfreesboro in July 1862, Duke assisted in the defeat of a Federal brigade at Hartsville, Tennessee, in which the Union loss was 2096, and the Confederate, 139. The Union commander, Colonel Moore, was one of the 1,834 prisoners taken on that occasion.

Morgan was promoted to brigadier general (his highest rank) on December 11, 1862.

On December 27, 1862, during Morgan’s Christmas Raid, Morgan and his 3000-man cavalry attacked Elizabethtown. During the battle, more than 100 cannon balls were fired into the town. Although Morgan successfully captured Elizabethtown, his goal was to disrupt the railroad. He proceeded north along the route of the railroad, burning trestles and destroying sections of the track.

At Kentucky’s Rolling Fork River, Duke was hit by a shell fragment while leading the rear guard as the rest of Morgan’s men crossed a stream on December 29, 1862. His men initially thought he was dead, but he survived.

The Ohio Raid

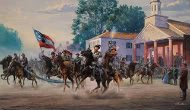

When General Bragg was preparing to fall back from Tullahoma, Tennessee in the summer of 1863, Morgan led 2500 Confederate cavalrymen on a daring three-week 700-mile raid through Indiana and Ohio. In this expedition, Colonel Duke was his right-hand man. Morgan and his men eluded pursuing Federal cavalry, diverted Federal troops and resources, and delayed important Northern military operations.

Image: Morgan’s Ohio Raid

Image: Morgan’s Ohio Raid

Mort Kunstler, Artist

The Rebel cavalry met staunch resistance by Midwestern civilians throughout the length of their raid, and were relentlessly pursued by determined Federal cavalry commanded by Generals Edward H. Hobson and Henry M. Judah.

In Montgomery, Ohio – a village near Cincinnatti – Morgan’s Raiders received a chilly reception from defiant townspeople. With Northern forces closing in, Morgan’s harried troops pushed on across Ohio. In the beleaguered South, news of Morgan’s Raid boosted morale.

Five days after Morgan had entered Montgomery, the Federal cavalry overtook the raiders in northeastern Ohio. Seven hundred Confederates were captured by the Federals at the Battle of Buffington Island on July 19, 1863. On July 26, 1863, Morgan was forced to surrender near West Point, Ohio – barely 70 miles from Lake Erie.

Duke and sixty-eight other Confederate officers were imprisoned in the Ohio Penitentiary at Columbus. Duke arrived at the penitentiary, a longstanding facility with individual cells, on August 1, 1863. Among his fellow prisoners were John Hunt Morgan and three other Morgan brothers.

So, poor Henrietta had not only her husband and four of her brothers in prison. Why Morgan and his command were sent to that particular facility, rather than to a military prison, has never been satisfactorily explained. It was certainly an unusual measure, and provoked more than a little outrage both among the prisoners and across the South. It suggested that the Confederates were being held as common felons, ineligible for the process of parole and exchange that had been agreed on by the combatants.

It seems likely that Union General-in-Chief Henry Halleck was determined to keep Morgan in custody for the duration of the war, denying him the possibility of returning to Confederate service, either by exchange or escape. The fact that Morgan’s command had looted liberally from the citizens of Ohio during the raid provided another premise for civil incarceration.

On the night of November 27, 1863, John Hunt Morgan and six others finished digging a tunnel and escaped over the penitentiary wall. The remaining prisoners at Columbus were sent to the military prison at Fort Delaware in March 1864.

Basil Duke would remain in captivity until August 3, 1864. He could have escaped with Morgan, but felt that to do so would hurt the chances of the escapees getting away – Morgan was easily replaced in his cell by his brother, but no similar replacement was there for Duke.

Meanwhile, Morgan was botching his assignment to protect southwestern Virginia. General John Hunt Morgan was killed by Union forces on September 4, 1864, in Greeneville, Tennessee, after a surprise attack on the house in which he was sleeping. Basil Duke took command of Hunt’s brigade, and was commissioned brigadier general on September 15, 1864.

In April 1865, upon hearing of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Duke hurried his command to Charlotte, North Carolina, and joined General Joseph E. Johnston’s army.

While General Johnston negotiated a surrender with USA General William Tecumseh Sherman, Duke joined the mounted escort of CSA President Jefferson Davis during his flight from the Confederate capital at Richmond through the Carolinas.

As Federal forces closed in, Davis dismissed his escort and continued on with a small bodyguard detachment. Upon Davis’ capture, eleven of the twelve troopers serving as his bodyguards were men of the 2nd Kentucky.

On May 2, 1865, Duke was at the final Confederate Council of War at the Burt-Stark Mansion in Abbeville, South Carolina – the last meeting of Davis and the cabinet members of the Confederate government. Davis hoped to continue the struggle, but met unanimous opposition, and realized theConfederate cause was lost.

General Basil Duke and the remnants of his cavalry entered Woodstock, Georgia, on May 8, 1865 and surrendered to a larger force of Federal cavalry. Per the last order given by the Confederate Secretary of War, Major General John Cabell Breckinridge, they were disbanded.

After the war, General Duke went back to Kentucky and made his home in Louisville, enjoying the esteem of his neighbors, who in true Kentucky spirit admire a brave man, whether they were with him or on the other side during the war. He was then a moderate, advocating reconciliation with the North. He neither advocated slavery, nor apologized for it; believing it was a good thing it was abolished, but that Northern claims of excessive abuse of slaves was exaggerated.

Basil Duke returned to his law practice, and his primary client was the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. He served as their chief counsel and lobbyist, despite the fact that the L&N was a favorite victim of Morgan’s Raiders during the war.

He briefly served in the Kentucky General Assembly from 1869 to 1870, resigning because he felt a conflict of interest being a lobbyist for the L&N Railroad. Duke also served as the Fifth Judicial District commonwealth attorney from 1875 to 1880.

Duke became greatly involved in writing the history of the Civil War and related topics. He helped to found Louisville’s Filson Club (now The Filson Historical Society) in 1884, writing many of their early papers. From 1885 to 1887, he edited the magazine Southern Bivouac, one of the best veterans’ magazines of the 1880s. He also wrote two first-rate books: A History of Morgan’s Cavalry (1867) and Reminiscences of General Basil W. Duke (a collection of various magazine articles he wrote, 1911).

After 1900, he began to withdraw from his public career. By 1903, he ceased doing work for the L&N.

In 1904, General Duke was appointed commissioner of Shiloh National Military Park by President Theodore Roosevelt – they had been introduced to each other at the Filson Club.

Henrietta Morgan Duke died of sudden heart failure on October 20, 1909 in Louisville, Kentucky, at the age of sixty-nine.

General Duke was devastated at losing his wife of 48 years. Afterward, he lived with his daughter Julia and her family in Louisville’s Cherokee Park.

In his final years, he spent much of his time handling requests for information about the Confederacy, even while recovering from cataract surgery in 1914. He was one of the few high-ranking Confederate officers still alive.

Brigadier General Basil Wilson Duke died on September 16, 1916 while visiting his daughter, Mary Currie, in Massachusetts. He had undergone surgery at a New York City hospital, first to have his right foot amputated on September 1, and then to have his right leg amputated at the knee on September 11. He was seventy-eight years old.

Image: Basil and Henrietta Duke Graves

Image: Basil and Henrietta Duke Graves

Lexington Cemetery

John Hunt Morgan’s grave is the white one in back.

Gary Robert Matthews’ Basil Wilson Duke, CSA, the definitive biography of this important but often overlooked figure in Civil War history, establishes that Duke was in fact the brilliant tactician behind much of the success of Morgan’s cavalry.

SOURCES

Basil W. Duke

Lexington Rifles

Morgan’s Cavalry

Basil Wilson Duke, CSA

Brigadier General Basil W. Duke