Conductor on the Underground Railroad

Harriet Tubman was an African American abolitionist, humanitarian and Union spy during the Civil War. After escaping from slavery, she made thirteen missions back to the land of her servitude to rescue scores of slaves, using the network of antislavery activists and safe houses known as the Underground Railroad.

Harriet Tubman was an African American abolitionist, humanitarian and Union spy during the Civil War. After escaping from slavery, she made thirteen missions back to the land of her servitude to rescue scores of slaves, using the network of antislavery activists and safe houses known as the Underground Railroad.

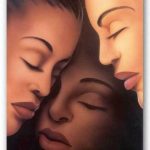

Image: Painting by Paul Collins:

Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad

She was born Araminta Ross around 1820 the fifth of nine children born to slave parents, Harriet (“Rit”) Green and Benjamin Ross, in Dorchester County on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. As with many slaves in the United States, neither the exact year nor place of her birth was recorded, and historians differ as to the best estimate. Harriet herself reported the year of her birth as 1825, while her death certificate lists 1815 and her gravestone says 1820.

Early Life

Harriet’s mother, Rit, was a cook for the Brodess family. Her father Ben was a skilled woodsman who managed the timber work on the plantation. They married around 1808, and according to court records, they had nine children together: Linah, Mariah Ritty, Soph, Robert, Minty (Harriet), Ben, Rachel, Henry, and Moses. Because Harriet’s mother was assigned to “the big house” and had little time for her own family, as a child, Harriet took care of a younger brother and a baby.

Edward Brodess had too many enslaved people to profitably use on his own plantation, so he hired them out frequently. At the age of five or six, Harriet was hired out as a nursemaid to a woman named “Miss Susan.” Harriet was ordered to keep watch on the baby as it slept; when it woke and cried, Harriet was whipped, leaving scars she carried for the rest of her life.

Harriet also worked as a child at the home of a planter named James Cook, where she had to go into nearby marshes to check the muskrat traps. Even after she caught the measles, she was sent into waist-high cold water. She became very ill and was sent back home. Her mother nursed her back to health, but she was immediately hired out again to various farms. As she grew older and stronger, she was assigned to grueling field and forest work: driving oxen, plowing, and hauling logs.

One day, when she was an adolescent, Harriet was sent to a dry-goods store to help the plantation cook purchase items for the kitchen. There, she met a slave owned by another family, who had left the fields without permission. His overseer was furious, and demanded that Harriet help restrain the young man. She refused to hold him down, and as the slave ran away, the overseer threw a two-pound metal weight from the store’s counter. It missed the boy and struck Harriet in the head, which she said “broke my skull.”

After that, she began to have seizures and would seemingly fall unconscious. Although she claimed to be aware of her surroundings, she appeared to be asleep. These episodes were alarming to her family who were unable to wake her when she fell asleep suddenly and without warning. This condition remained with her for the rest of her life.

This severe head wound occurred at a time in her life when Harriet was becoming deeply religious. Though Harriet was illiterate, her mother had told her Bible stories, and she acquired a passionate faith in God. After her brain trauma, she began experiencing powerful visions and vivid dreams, which she considered signs from the Lord.

By 1840, her father Ben was manumitted – freed from slavery – at the age of forty-five, as stipulated in a former owner’s will. He continued working as a timber estimator and foreman for the Thompson family, who had owned him as a slave.

Several years later, Harriet contacted a white attorney and paid him five dollars to investigate her mother’s legal status. The lawyer discovered that a former owner had issued instructions that Rit, like her husband, would be manumitted at the age of forty-five. The record showed that a similar provision would apply to Rit’s children, and that any children born after she reached forty-five years of age were legally free. However, the Pattison and Brodess families had ignored this stipulation when inheriting the slaves, and Harriet could do nothing more about it.

Marriage and Family

About 1844, Harriet married a free black man named John Tubman. Although little is known about him or their time together, the union was complicated due to her slave status. Since the mother’s status dictated that of her children, any children born to Harriet and John would be enslaved. Such blended marriages – free people marrying enslaved people – were not uncommon on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where half the black population was free. Soon after her marriage, she changed her name from Araminta to Harriet, her mother’s name, possibly as part of a religious conversion.

The Escape

In 1849, Harriet Tubman became ill, and her value as a slave was diminished as a result. Her master Edward Brodess tried to sell her, but he died. His widow Eliza began working to sell the family’s slaves, but Harriet refused to wait for the Brodess family to decide her fate, despite her husband’s efforts to dissuade her. “[T]here was one of two things I had a right to,” she explained later, “liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other.”

Tubman and her brothers Ben and Henry escaped from slavery on September 17, 1849. She had been hired out to Dr. Anthony Thompson, who owned a very large plantation called Poplar Neck in neighboring Caroline County, and it is likely her brothers worked for Thompson there as well. But Harriet’s brothers had second thoughts. Ben had just become a father, and the two men – fearful of the dangers ahead – went back, forcing her to return with them.

Soon afterwards, Tubman escaped again, this time without her brothers. The night before she left, she tried to send word to her mother of her departure. She located Mary, a trusted fellow slave, and sang a coded song of farewell: “I’ll meet you in the morning,” she intoned, “I’m bound for the promised land.”

While her exact route is unknown, Tubman used the extensive network known as the Underground Railroad. This informal but well-organized system was composed of free and enslaved blacks, white abolitionists and other activists. Most prominent among the latter in Maryland at the time were members of the Society of Friends, often called Quakers.

The Preston area near Poplar Neck in Caroline County, Maryland, contained a significant Quaker community, and was probably Tubman’s first stop during her escape. From there, she probably took a common route for fleeing slaves: northeast along the Choptank River, through Delaware and then north into Pennsylvania. A journey of nearly ninety miles on foot would take between five days and three weeks.

Tubman’s dangerous journey required her to travel by night (guided by the North Star), avoiding the careful eyes of “slavecatchers,” eager to collect rewards for fugitive slaves. The conductors of the Underground Railroad used a variety of deceptions to hide and protect her. At one of the earliest stops, the lady of the house ordered Harriet to sweep the yard to make it appear as though she worked for the family.

When night fell, the family hid her in a cart and took her to the next friendly house. Given her familiarity with the woods and marshes of the region, it is likely that Harriet hid in those areas during the day. Because the routes she followed were used by other fugitive slaves, she did not speak about them until later in her life.

Tubman crossed into Pennsylvania with a feeling of relief and awe, and recalled the experience years later:

When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.

Stranger in a Strange Land

Immediately after reaching the city of Philadelphia, Tubman began thinking of her family. She worked odd jobs and saved her money. About the same time, the U.S. Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which forced law enforcement officials (even in states where slaver was outlawed) to aid in the capture of fugitive slaves, and imposed heavy punishments on those who helped them escape.

Image: ‘Step on Board’ Memorial

Image: ‘Step on Board’ Memorial

This poignant monument stands in at the corner of Columbus Avenue and Pembroke Street in Boston’s South End. Tubman is known to have visited the Charles Street Meeting House at Mount Vernon and Charles Street to discuss emancipation with area abolitionists.

In December 1850, Tubman learned that her niece Kessiah was going to be sold in Maryland. Horrified at the prospect of having her family broken further apart, Tubman voluntarily returned to the land of her enslavement. She went to Baltimore, where her brother-in-law Tom Tubman hid her until the time of the sale.

Kessiah’s husband, a free black man named John Bowley, made the winning bid for his wife. Then, while he pretended to make arrangements to pay, Kessiah and her children went to a nearby safe house. When night fell, Bowley rowed the family on a log canoe sixty miles to Baltimore. There they met Tubman, who brought the family safely to Philadelphia.

The following spring, Tubman went back into Maryland to help guide away other family members. On this, her second trip, she brought back her brother Moses, and two other unidentified men. On her third return, she went after her husband, only to find he had taken another wife.

Word of her exploits had encouraged her family, and she became more confident with each trip. As she led more and more individuals out of slavery, Harriet Tubman became known as Moses – an allusion to the prophet who led the Hebrews to freedom.

Because the Fugitive Slave Law had made the northern United States more dangerous for escaped slaves, many began migrating further north to Canada. In December 1851, Tubman guided an unidentified group of eleven fugitives – possibly including the Bowleys and several others she had helped rescue earlier – northward.

For eleven years, Tubman returned again and again to the Eastern Shore of Maryland, rescuing some seventy slaves in thirteen expeditions, including her three other brothers, Henry, Ben and Robert, their wives and some of their children. She also provided specific instructions for about fifty to sixty other fugitives who escaped to the north.

Her dangerous work required tremendous ingenuity. One admirer said: “She always came in the winter, when the nights are long and dark, and people who have homes stay in them.” Once Tubman had made contact with escaping slaves, they left town on Saturday evenings, since newspapers would not print runaway notices until Monday morning. She also carried a revolver, and was not afraid to use it.

Slaveholders in the region, meanwhile, never knew that “Minty”, the petite, five-foot-tall, disabled slave who had run away years before and never come back, was behind so many slave escapes in their community. In fact, by the late 1850s, they began to suspect a northern white abolitionist was secretly enticing their slaves away.

One of Tubman’s last missions into Maryland was to retrieve her aging parents. Her father had purchased her mother in 1855 from Eliza Brodess for twenty dollars. But when they were both free, the area became hostile to their presence. Two years later, Tubman received word that her father had harbored a group of eight escaped slaves, and was at risk of arrest. She traveled to the Eastern Shore and led them north into the Canadian city of St. Catherines, Ontario, where a community of former slaves (including her relatives and many friends) had gathered.

In April 1858, Tubman was introduced to the abolitionist John Brown, who advocated the use of violence to destroy slavery in the United States. Although she never advocated violence against whites, she agreed with his course of direct action and supported his goals. Like Harriet, he spoke of being called by God, and trusted the divine to protect him from the wrath of slaveholders.

As he began recruiting supporters for an attack on slaveholders, Brown was joined by General Tubman, as he called her. Her knowledge of support networks and resources in the border states of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware was invaluable to Brown.

Although other abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison did not endorse his tactics, Brown dreamed of fighting to create a new state for freed slaves, and made preparations for military action. After he began the first battle, he believed, slaves would rise up and carry out a rebellion across the south. He asked Harriet to gather former slaves then living in Canada, who might be willing to join his fighting force, which she did.

On May 8, 1858, John Brown held a meeting in Ontario, where he unveiled his plan for a raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia. When word of the plan was leaked to the government, Brown put the scheme on hold and began raising funds to try again, and Harriet Tubman helped him.

During this time, Tubman was busy giving lectures to abolitionist audiences and tending to her relatives. In the autumn of 1859, as Brown and his men prepared to launch the attack, she could not be contacted. When the raid on Harpers Ferry took place on October 16, Tubman was not present. Brown’s raid failed; he was convicted of treason and hanged in December.

In early 1859, abolitionist U.S. Senator William Seward sold Tubman a small piece of land on the outskirts of Auburn, New York. The city was a hotbed of antislavery activism, and she seized the opportunity to deliver her parents from the harsh Canadian winters. But returning to the U.S. meant that escaped slaves were at risk of being returned to the south under the Fugitive Slave Law. Her land in Auburn became a haven for her family and friends. For years, she took in relatives and boarders, offering a safe place for black Americans seeking a better life in the north.

The Civil War

When the Civil War began, Harriet Tubman saw a Union victory as a key step toward the abolition of slavery. She worked for the Union Army, first as a cook and nurse, and then as an armed scout and spy.

Tubman joined a group of Boston and Philadelphia abolitionists heading to the Hilton Head District in South Carolina. She became a fixture in the camps, particularly in Port Royal, South Carolina, assisting fugitives. Harriet soon met General David Hunter, a strong supporter of abolition. He declared that all of the slaves in the Port Royal district were free, and began gathering former slaves for a regiment ofblack soldiers.

But President Abraham Lincoln was not prepared to enforce emancipation in the southern states, and reprimanded Hunter for his actions. Harriet Tubman condemned Lincoln’s response (and his general unwillingness to consider ending slavery in the United States), for both moral and practical reasons. “God won’t let master Lincoln beat the South till he does the right thing,” she said.

Tubman served as a nurse in Port Royal, preparing remedies from local plants and aiding soldiers suffering from dysentery. She cared for men with smallpox; that she did not contract the disease herself started more rumors that she was blessed by God.

At first, she received government rations for her work, but newly freed blacks thought she was getting special treatment. To ease the tension, she gave up her right to these supplies and made money selling pies and root beer, which she made in the evenings.

When Lincoln finally put the Emancipation Proclamation into effect in January 1863, Harriet considered it an important step toward the goal of liberating all black men, women and children from slavery. She renewed her support for a defeat of the Confederacy, and before long she was leading aband of scouts through the land around Port Royal.

The marshes and rivers in South Carolina were similar to those of the Eastern Shore of Maryland, and Harriet’s knowledge of covert travel and subterfuge among potential enemies were put to good use. Her group, working under the orders of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, mapped the unfamiliar terrain and collected information from its inhabitants.

On the morning of June 2, 1863, Tubman guided three steamboats around Confederate mines in the waters of the Combahee River. Once ashore, Union troops set fire to plantations and seized thousands of dollars worth of food and supplies. When the steamboats sounded their whistles, slaves throughout the area understood that they were being liberated. Harriet watched as slaves stampeded toward the boats. More than seven hundred slaves were rescued in the Combahee River Raid.

For two more years, Tubman worked for the Union forces, tending to newly liberated slaves, scouting into Confederate territory, and eventually nursing wounded soldiers in Virginia. After the war, Tubman retired to her home in Auburn, New York, where she cared for her aging parents.

Despite her years of service, Harriet Tubman had never received a regular salary and was for years denied compensation. Her unofficial status caused great difficulty in documenting her service, and the U.S. government was slow in recognizing its debt to her. She did not receive a pension for her service in the Civil War until 1899.

Her constant humanitarian work for her family and former slaves, meanwhile kept her in a state of constant poverty, and her difficulties in obtaining a government pension were especially taxing for her.

Late Years

Harriet Tubman spent her remaining years in Auburn. She worked various jobs to support her elderly parents, and took in boarders to help pay the bills. One of the people she took in was a Civil War veteran named Nelson Davis. He began working as a bricklayer, and they soon fell in love. Though he was twenty-two years younger than she, they were married on March 18, 1869. They spent the next twenty years together, and in 1874 they adopted a baby girl named Gertie.

Tubman’s friends and supporters from the days of abolition, meanwhile, raised funds to support her. Because of the debt she had accumulated (including delayed payment for her property in Auburn), Tubman fell prey to a swindle in 1873. Two men attacked her and knocked her out with chloroform, then stole her purse and bound and gagged her. When she was found by her family, she was dazed and injured, and the money she had borrowed from a friend was gone.

In her later years, she was active in the women’s suffrage movement, and was soon working alongside women such as Susan B. Anthony. Harriet traveled to New York, Boston and Washington, DC to speak out in favor of women’s voting rights.

This kindled a new wave of admiration for Harriet among the press in the United States. An 1897 suffragist newspaper reported a series of receptions in Boston honoring Harriet Tubman and her lifetime of service to the nation. But her endless contributions to others had left her in poverty, and she had to sell a cow to buy a train ticket to these celebrations.

As Harriet aged, the sleeping spells and suffering from her childhood head trauma continued to plague her. At some point in the late 1890s, she underwent brain surgery in Boston. Unable to sleep because of pain and “buzzing” in her head, she asked a doctor if he could operate. He agreed, and in her words, “sawed open my skull, and raised it up, and now it feels more comfortable.”

Image: Harriet Tubman in 1911

Image: Harriet Tubman in 1911

By 1911, her body was so frail that she had to be admitted to the rest home that was named in her honor. A New York newspaper described her as “ill and penniless,” prompting supporters to offer a new round of donations.

Harriet Tubman died on March 10, 1913, surrounded by friends and family members. Just before she died, she told those in the room: “I go to prepare a place for you.” She was buried with military honors at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, New York.

My Favorite Harriet Tubman Quote

I had reasoned this out in my mind. There was one of two things I had a right to – liberty or death. If I could not have one, I could have the other, for no man should take me alive. I shall fight for my liberty and when the time comes for me to go, the Lord will let them kill me.

SOURCES

Harriet Tubman

Africans in America

About Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman Biography

Wikipedia: Harriet Tubman

Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman