Writer, Abolitionist and Women’s Rights Activist

Frances Dana Gage was a leading reformer, feminist and abolitionist. She worked closely with other leaders of the early women’s rights movement. She was among the first to champion voting rights for all citizens, without regard to race or gender.

Frances Dana Gage was a leading reformer, feminist and abolitionist. She worked closely with other leaders of the early women’s rights movement. She was among the first to champion voting rights for all citizens, without regard to race or gender.

Childhood and Early Years

On October 12, 1808, Frances Dana Barker was born in Union, Ohio. Her parents were among the first settlers in the United States Northwest Territory. A farmer’s daughter, Frances was educated at a log cabin in the woods, spun the garments she wore, made cheese and butter, and did outdoor chores.

Frances made frequent visits to her grandmother, Mary Bancroft Dana, whose home was at Belpre, Ohio. Mary Dana was a radical on the subject of slavery, and Frances learned from her to hate the word, and all it represented. Frances was frequently laughed at in childhood because she sympathized with the poor fugitives from slavery, who often found their way to the neighborhood in which she lived, seeking the kindness and charity of the people.

It had not yet become a crime to help a slave, and Mrs. Barker often sent her daughter on errands of mercy to the nearby cabins where fugitive slave sought shelter, often to be caught and sent back to their masters. Frances early became familiar with their suffering and their needs.

At the age of twenty, on January 1, 1829, Frances Barker married James L. Gage, an abolitionist lawyer from McConnellsville, Ohio, who also hated the system of slavery in the South. Moral integrity, and unflinching fidelity to the cause of humanity, were leading traits of his character.

Frances Gage was a dedicated advocate of the social reform movements that were organized during the decades before the Civil War, and she always found herself in a minority through all the struggling years between 1832 and 1865. The great moral struggle, in her opinion, required far more heroism than that which marshaled our hosts along the Potomac, prompted Sheridan’s raids, or Sherman’s triumphant March to the Sea.

Literary Career

The editor of the State Journal invited her to write weekly for his columns during a year. This, at that time seemed to her a great achievement. But when she wrote about her opposition to the Fugitive Slave Law, the editor sent a note saying her services were no longer wanted.

Gage’s professional writing career brought her regional fame. Writing in The Ohio Cultivator and other regional journals as Aunt Fanny, she offered a warm domestic persona who offered advice and support to isolated housewives in Ohio. She wrote letters, essays, poetry, children’s stories and novels. She also contributed to the Western Literary Magazine, New York’s Independent, Missouri Democrat, Cincinnati’s Ladies Repository, Field Notes, The National Anti-Slavery Standard, Una and Jane Grey Swisshelm’s Saturday Visiter.

Gage extended her circle of acquaintances beyond Ohio by writing letters to women she admired. Amelia Bloomer, engaged her to write for the New York State temperance newspaper, The Lily. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, whose 1848 Seneca Falls Convention launched the women’s rights movement in America, was also on the staff.

Career in Reform

In all her warfare against social wrongs – temperance, slavery and women’s rights – Gage’s fight for the rights of her own gender subjected her to the most trying persecution and insult. In the region of Ohio where she lived, she stood almost alone, but she was never inclined to yield.

In 1851, Gage presided over a women’s rights convention in Akron, Ohio, where her opening speech introducing Sojourner Truth attracted much attention. Later, Gage recorded her recollection of Truth’s speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?” Her version has become the standard text and account of that famous speech.

Gage stepped comfortably into the roles of public organizer and orator. She was a talented public speaker for more than 30 years to audiences of both men and women. She worked as Stanton’s agent, canvassing for signatures in New York State and Ohio, and supported Susan B. Anthony‘s program to make legal changes in the state laws.

Between 1853 and 1857, the Gages lived in St. Louis, Missouri. Missouri was a slave state, and Gage’s ideas and her submissions to local newspapers were not welcome. She boldly stated her beliefs whenever the opportunity arose, and was often threatened with violence due to her anti-slavery views. She was soon branded as an abolitionist, and the family endured threats of violence and attempts to burn them out.

Because of her husband’s failure in business at St. Louis and his ill-health, she took a job as Editor of the Home Department of an agricultural paper in Columbus, Ohio in 1860. The war destroyed the circulation of the paper, and she was again without work. But in 1861, she took part in the political campaign that led to the passage of Ohio’s first Woman’s Rights Bill.

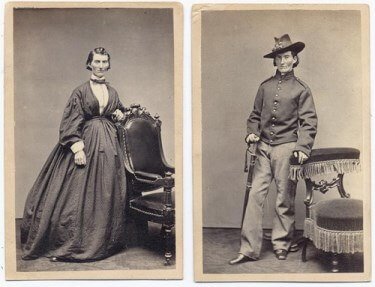

In 1861 when the Civil War began, four of the Gage sons joined the Union Army, and Frances began lecturing on supporting the troops. The call for help for the soldiers was responded to by all loyal women. Mrs. Gage did what she could with her hands, but found her tongue and pen were much more efficient agents.

The Freedmen

In the autumn of 1862, Frances and her daughter Mary went to the Sea Islands in South Carolina to train ex-slaves. As Superintendent of Parris Island, she proved to be a capable organizer. There she met and befriended nurse Clara Barton, who was working at nearby Hilton Head. Barton recorded in her diaries how much she learned from Aunt Fanny, who had expanded her notions of injustice to include freedmen’s and women’s rights.

James Gage became critically ill and died before Frances could reach his side in Ohio. When she returned to Parris Island, she learned that Barton was moving on. Gage briefly served at another medical facility in Fernandina, Florida, then returned to the North, having worked in the war-torn South for over a year.

The Lecture Circuit

In the fall of 1863, Frances Gage returned north, and began a lecture tour, speaking to the people of her “experiences among the Freedmen.” She gave a truthful portrayal of slavery and its barbarity, its demoralization of master and man, and the intensely human character of the slave, who for two hundred years had preserved so much goodness, hope and a desire for knowledge.

She believed that by removing prejudice and inspiring confidence in the Emancipation Proclamation, and by striving to unite the people on this great issue, she could do more than in any other way to end the war and relieve the soldier – such was the aim of her lectures.

Thus, in all the inclement winter weather – through Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, Illinois and Missouri – she pursued her labors of love, never omitting an evening when she could get an audience to address, speaking for Soldiers’ Aid Societies and giving the proceeds to those who worked only for the soldier, then for Freedmen’s Associations. She worked without fee or reward, asking only of those who were willing to give enough to defray her expenses.

In the summer of 1864, Gage traveled down the Mississippi to help the injured at Memphis, Vicksburg, and Natchez. She went as an unsalaried agent of the Western Sanitary Commission, receiving only her expenses, and the goods and provisions to relieve the want and misery of the suffering soldiers.

A few months’ experience among the Union refugees and fugitives convinced her that her best work for all was in the lecturing field, in rousing the hearts of the multitude to good deeds. She had but one weak pair of hands, while her voice might set a hundred pairs in motion, and believing that we err if we fail to use our best powers for life’s best uses, she again entered the lecture field in the west, speaking almost nightly.

After the war women’s rights leaders and friends like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Amelia Bloomer, Lucy Stone and Antoinette Brown encouraged Gage to be the women’s rights emissary in America’s Midwest. Her lecture circuit included Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee.

In September 1865, Gage was crippled when her carriage overturned at Galesburg, Illinois, after she spoke at Edward Beecher’s Indiana church. After recuperating at her daughter’s home for nearly a year, she decided to move to Lambertsville, New Jersey. This put her closer to publishers, other activists and national meetings that were often held in New York City and Philadelphia.

In her Address to the First Anniversary of the American Equal Rights Association in 1867, she asked that women should get the vote: “Because it is right, and because there are wrongs in the community that can be righted in no other way.” She also complained about social attitudes that restricted women to the household: “You have attempted to mold seventeen millions of human souls in one shape, and make them all do one thing.”

Soon thereafter, Gage was permanently disabled by a stroke. Meanwhile the women’s suffrage organizations were reorganized and redirected. Frances could not participate in the political strategizing, nor could she travel or address audiences, so she focused instead upon writing novels, using this medium to promote temperance and women’s rights.

After being an invalid for years, Frances Dana Gage died in Greenwich, Connecticut on November 10, 1884.

Frances Dana Gage Quote:

When we hold the ballot, we shall stand just there. Men will forget to tell us that politics are degrading. They will bow low, and actually respect the women to whom they now talk platitudes; and silly flatteries, sparkling eyes, rosy cheeks, pearly teeth, ruby lips, the soft and delicate hands of refinement and beauty, will not be the burden of their song; but the strength, the power, the energy, the force, the intellect and the nerve, which the womanhood of this country will bring to bear… must make all its men and women wiser and better.

SOURCE

Frances Dana Barker Gage

Woman’s Work in the Civil War