Wife of Union General Romeyn Beck Ayres

Emily Gerry Dearborn was born May 8, 1829, in Bangor, Maine; daughter of Greenlief and Pamela Gilman Dearborn. Romeyn Beck Ayres was born on December 20, 1825, at East Creek, New York, along the Mohawk River in upstate New York. He was the son of a small town doctor who urged all of his sons into professional careers.

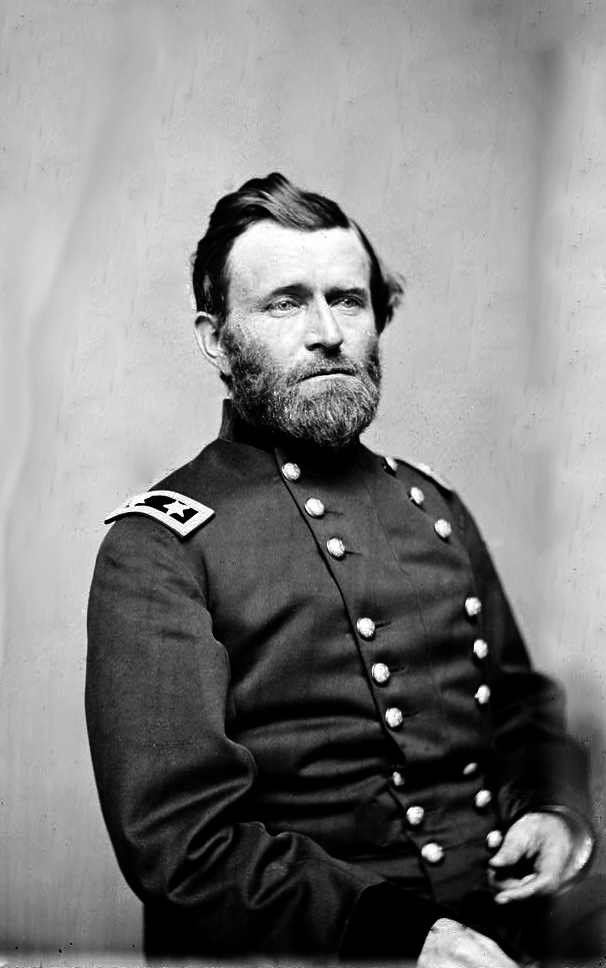

Image: Romeyn Beck Ayres

Romeyn was singled out for a military career and was tutored rigorously in Latin by his father. He entered West Point, where he was an indifferent scholar, graduating 22nd out of the 38 members of the class of 1847, which included future Confederate Generals A.P. Hill, George Steuart and Henry Heth, as well as future Union Generals Ambrose E. Burnside, John Gibbon and Charles Griffin.

In 1849, Ayres married Emily Gerry Dearborn in Bangor, Maine. They had one child, Charles Greenlief Ayers, born in 1854.

Although graduating in time for the Mexican-American War, Ayers served only on garrison duty in Puebla and Mexico City until 1850, seeing no fighting in the war. He was posted to the artillery and entered the humdrum army life of the 1850s, serving in garrisons in the East and on the frontier. He developed the usual Regular Army observance of regulations, but retained a commonsense rebelliousness, a paradoxical streak that stayed with him throughout his career.

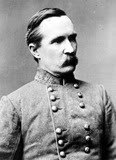

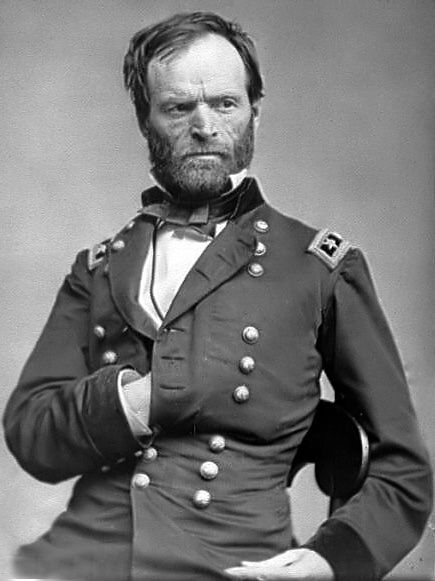

At the beginning of the Civil War, Ayres was promoted to captain and commanded a battery in the 5th US Artillery, which he led in the First Bull Run Campain in July 1861, and was heavily involved in the Battle of Blackburn’s Ford immediately before the larger battle. At Bull Run, his battery, attached to the brigade of William Tecumseh Sherman, was held in reserve, and Ayres did not see action during the battle, but distinguished himself by providing cover for retreating Union Army troops, who were pursued by the Confederate cavalry.

In October 1861, he was named as Chief of Artillery for Brigadier General William F. Smith’s Division, which would become part of the Army of the Potomac’s VI Corps. Ayres rose swiftly in the artillery, fighting in the Peninsula Campaign and at Antietam, after which he had to take sick leave of nearly three months to recuperate from an injury caused when his horse fell.

He was promoted to to Brigadier General and made Chief of Artillery for the VI Corps as of November 29, 1862. At the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, he commanded the corps artillery, which made up part of the formidable Union artillery position across the Rappahannock River on Falmouth Heights. All of his performances in these battles were followed by numerous commendations by officers who obviously admired his ability.

While recuperating, Ayres considered had realized that artillery officers had a much slower rate of promotion than their colleagues in the infantry. He arranged for a transfer and became an infantry brigade commander in the Second Division of the V Corps as of April 21, 1863. This division was known as the Regular Division because it consisted entirely of regular army (versus state volunteers) soldiers, and he led its First Brigade in the Battle of Chancellorsville, where the V Corps was only lightly engaged.

Thirty-eight-year-old Romeyn Ayres was a career army officer, a competent professional at the head of the only division of professional soldiers in the Army of the Potomac. Six feet tall, he had grown portly and was balding so as to leave him with a topknot. He sported a massive, wiry beard and spiky mustache that nearly hid his mouth and ears, making him look older than he was. His high intelligent forehead and philosophical gaze imparted the air of a stoic, yet the mere size of the man asserted authority.

He was a very social man in the best sense of the word; considerate of others and full of fun without sacrificing his dignity to indulge it. He had adopted extremely meticulous personal habits and was an immaculate dresser. Despite his cultivated appearance, Ayres acquired the reputation of a stubborn fighter who convinced his men early on that they could expect to be driven hard.

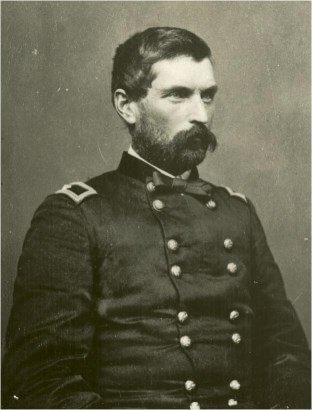

Image: Romeyn Beck Ayres

In late June 1863, Ayres assumed command of the Second Division in the chain of promotions brought about by Major General George G. Meade’s ascension to command of the Army of the Potomac – Major General George Sykes taking Meade’s place at the head of the V Corps, and Ayres taking Sykes’ place – which occurred only three days before the crucial battle at Gettysburg. Ayres had risen to division command quickly for an officer with little infantry experience.

Command of an infantry division was a new and untried responsibility for Ayres, but he was a career soldier who had shown rare ability as a divisional and corps artillery commander through much of the war, and his character and professional training suited him extremely well for the job. Also, the Regulars were the division most likely to perform correctly without any commander at all, out of sheer force of habit.

On July 1, while the battle of the first day was being fought on the ridges west of Gettysburg, Ayres was with the main V Corps column, marching from Union Mills to Hanover, then heading toward Gettysburg about 7 o’clock in the evening.

Ayres’s division arrived at Gettysburg battlefield at 11 o’clock on the morning of July 2. The men immediately went into camp near Powers Hill and rested for a few hours. That afternoon, Ayres’ brigades were hurried to the Union left with the rest of the V Corps when CSA General James Longstreet’s Corps threatened that flank about 4 o’clock.

Soon after they arrived on the scene, corps commander Major General George Sykes directed Ayres to bring his brigades to the support of General John Caldwell’s division, which was counterattacking the Rebels in the Wheatfield. Ayres advanced, heading west from Plum Run Valley into the woods on the east side of the Wheatfield, and while he was conferring with Caldwell on the best next step, an aide noticed that Caldwell’s men were running away on the right.

The cause of the Union flight was the Confederate breakthrough at the Peach Orchard nearby, which opened the way for a flood of Southerners to stream past the Wheatfield and around Ayres’s right, threatening to surround him. Ayres’s brigades were forced to retreat as well, suffering heavy casualties. His men rallied just north of Little Round Top, where they remained for the rest of the Battle.

At Gettysburg, Ayres and his Regulars never had a chance to show how well they could fight. Ayres escaped any personal blame – he was included in Sykes’ praise of all the Fifth Corps division leaders. After Gettysburg, the Regular Division was sent to New York City to suppress the draft riots there.

In the Army of the Potomac reorganization of March 1864, which reduced the number of corps from five to three, Ayres was replaced by Brigadier General Charles Griffin. Ayres was reduced to commanding the Fourth Brigade of the First Division, V Corps.

He fought in subsequent actions of V Corps, commanding Fourth Brigade, First Division in March 1864; First Brigade, First Division from the Wilderness through Cold Harbor, April – June 1864; then the Second Division from June 1864 to January 1865, at Petersburg, where he was wounded.

Ayres led his brigade though the battles of General Ulysses S. Grant’s Spring 1864 Overland Campaign – at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Yellow Tavern, the North Anna, Totopotomoy, and Cold Harbaor. Ayres was again made a division commander, leading the Second Division, V Corps, through the Petersburg Campaign, where he was wounded in June 1864, but returned to duty in August.

On August 1, 1864, Ayres received a brevet promotion to Major General of Volunteers for his contributions in these campaigns; he received particular commendations for Weldon Railroad and Five Forks. He was present at the final engagements, ending with the surrender of Lee’s army at Appomattox on April 9, 1865.

He was mustered out of the volunteer service as Major General of V on April 30, 1866. As part of the general reduction of ranks that typically follow American wars, Ayres returned to the regular army with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, and he performed mostly garrison duty in a number of posts in the South.

In 1879, Ayres was promoted to Colonel of the Second United States Artillery, and was on active duty at Fort Hamilton, New York City, when he married Juliet Opie Hopkins Butcher, daughter of famed Confederate nurse Juliet Opie Hopkins, on January 29, 1880.

General Romeyn Beck Ayres died at Fort Hamilton, New York, on December 4, 1888, at the age of 62. On December 7, 1888, Ayres’ funeral was held at St. John’s Church. The coffin, draped with the American flag and with the General’s sword and belt lying on its lid, was borne to a gun carriage standing in front of the church. About 250 officers and men of the Fifth Artillery and Second Artillery were drawn up along the road at salute as the coffin was placed on the carriage, and then led the way to the wharf where the steamer Chester A. Arthur lay waiting.

Mrs. Ayres was lying ill at the Fort from the shock of her husband’s death, and all of the General’s children were stationed at far-away posts, so his only relative at the funeral was his daughter-in-law, Mrs. Charles Ayres.

The general was interred on December 7, 1888, in the Ayers family plot at Arlington National Cemetery.

Juliet Hopkins Ayres died on November 26, 1925.

SOURCES

Romeyn B. Ayres

Romeyn Beck Ayres

Major General, United States Army

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Brigadier General Romeyn Beck Ayers