Sister of Mary Todd Lincoln

In October 1839, twenty-year-old Mary Todd moved to Springfield, Illinois to live with her older married sister Elizabeth Todd Edwards. As was the custom, Elizabeth served as Mary’s guardian. Despite their sometimes rocky relationship, Elizabeth rescued Mary Todd Lincoln from an insane asylum in 1875, and gave her a home.

Image: Elizabeth Todd Edwards and Mary Todd Lincoln

Elizabeth Todd was born in 1816 in Lexington, Kentucky. Her sister Mary was born on December 13, 1818. Their mother Eliza Parker Todd died of a post-birth bacterial infection in 1824. Fourteen months later, their father Robert Todd married Elizabeth Humphreys. Over the next 15 years, nine half-siblings joined the family. Mary did not get along with her stepmother and felt rejected by her father.

Elizabeth Todd met Ninian Edwards when he came to Lexington to study law at Transylvania University. They married on February 14, 1832, and remained in Lexington until Ninian graduated the following. Shortly thereafter, Ninian’s father died and the couple moved to Illinois. Edwards began his law practice in 1833, and in 1834 was appointed attorney general of Illinois, but resigned in 1835 when the family moved to Springfield, Illinois.

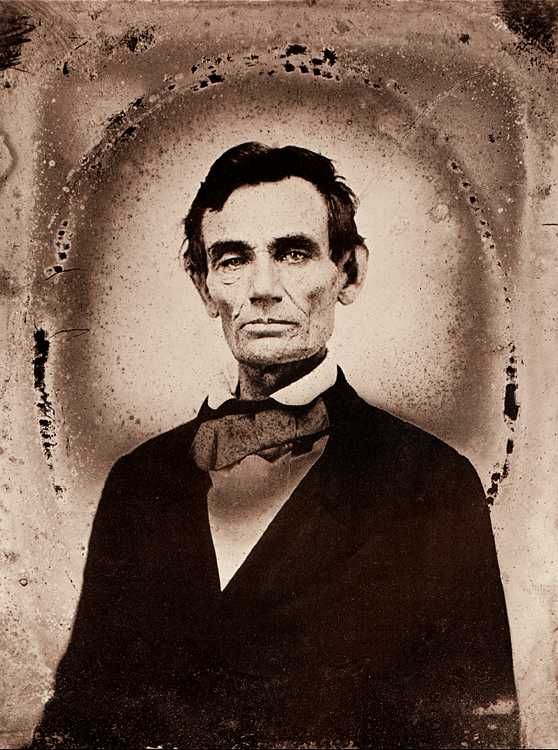

The Many Connections of Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln

John Todd Stuart, originally from Lexington, Kentucky and a favorite cousin of Elizabeth and Mary Todd, studied law and opened a practice in Springfield, Illinois. He had been a major in the Black Hawk War in 1832, where he first met Abraham Lincoln, who was in the same battalion. In the course of the war the two began a life-long friendship, before he met any of the other members of the Todd clan.

Lincoln and Stuart also served as fellow members of the Illinois legislature in 1834. Lincoln was unsure about his future until Stuart persuaded Lincoln to study for the bar, and continue in politics. Lincoln studied the law books Stuart lent him, passed the bar, and established a law practice with Stuart in 1837. These were major steps for the young backwoodsman.

Ninian Edwards first met Abraham Lincoln in the mid-1830s when the two were Whigs serving in the Illinois State Legislature. Together Edwards and Lincoln worked successfully to move the State Capital to Springfield. Edwards remained a member of the legislature continuously until 1852. Historian Stephen Berry wrote:

Ninian Edwards would serve in the state legislature off and on in one capacity or another for more than twenty years. But he was a ‘thousand things’ short of Lincoln… he would occasionally resent Lincoln’s success, but he would always, if grudgingly, recognize his superiority. Within the first year, he had talked so much of Lincoln that his wife and her sister Frances, who was visiting, demanded that he bring the man by.

Elizabeth and Ninian Edwards lived in a fine house in an area known as Aristocracy Hill. The spaciousness of their home allowed them to entertain guests, and Elizabeth Todd Edwards used the spare bedrooms to invite her sisters to visit for extended periods, always looking for suitable spouses for her sisters. The strategy worked; all three of Elizabeth’s younger sisters married men from Springfield.

Historians have cited the Springfield visits of the Todd sisters as evidence of the strained relations between the offspring of Robert Smith Todd’s first wife, Eliza Ann Parker, and his second wife, Elizabeth Humphreys. Springfield became an avenue of escape from the overcrowded Todd home in Lexington.

The Edwards mansion was the social gathering spot for the promising as well as the already established politicians and lawyers, and Abraham Lincoln was drawn there soon after he moved to Springfield in 1836. Lincoln was a frequent guest who was often the life of the party, telling stories and charming the room with his wit.

Elizabeth Edwards invited twenty-year-old Mary Todd to live with her in Springfield, and Mary moved into the Edwards home permanently in October 1839. As was the custom at the time, the Edwardses served as Mary’s guardian. Mary met Abraham Lincoln at a social event at the Edwards home that fall; she was almost ten years younger than he.

Despite his rough exterior and rougher manners, Mary was drawn to Lincoln and often defended him from family criticism. Her niece Katherine Helm later wrote:

Her cousins noticed that Mary flared into defense at the least criticism of Lincoln, although she herself still made a little – a very little – mild fun of the young lawyer. Mr. and Mrs. Edwards at last became alarmed at Mary’s evident preference, and feeling their responsibility as her guardians, they strongly objected and pointed out to Mary the incongruity of such a marriage. Although Mr. Lincoln was honorable, able and popular, his future, they said, was nebulous, his family relations were on a different social plane. His education had been desultory. He had no culture, he was ignorant of social forms and customs, he was indifferent to social position.

Mary might have been uncertain about her feelings for Lincoln at first. Her half-sister, Emilie Todd Helm, later recalled how their cousin gave Mary a new understanding of Abraham Lincoln:

It was cousin John Todd Stuart who gave her an insight into Lincoln’s real character. She heard him tell, at a family gathering, of Lincoln’s amusing blunders in the Black Hawk War. Noting her feelings, Stuart launched into a panegyric of Lincoln’s intellect. Mary idolized intellect.

He told her how quickly Lincoln had mastered the science of law; how keen and honest his insight into matters of right and wrong; how unerring his judgment; how quick-witted he proved himself in quoting sentences applicable to a particular case from the Bible, Shakespeare, Robert Burns or other authors he had absorbed and made his own; how surprisingly he had mastered the English language and how clearly, forcibly and eloquently he expressed his thought.

Then with a note of tenderness Stuart described the dignity and nobility of his partner in defending the just cause of a poor and ignorant man. He told of his scorn for an ignoble action and of his scathing ridicule of a political demagogue in the opposition, making the audience roar with laughter and converting their sympathies and votes to his own side.

John Todd Stuart was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1839, leaving Lincoln to run their law practice alone. He handled many cases and learned the ins and outs of the legal system very quickly.

Mary’s Engagements and Marriage

Meanwhile, Mary and Abraham fell in love and became engaged in less than a year. Elizabeth and Ninian Edwards did not approve of the engagement because Lincoln had neither a suitable background nor the financial means to support Mary in the manner to which she was accustomed. Elizabeth’s son later remembered “My mother did what she could to break up the match.”

Lincoln knew their opinion of him, and he was also beset by problems in his political and professional life at that same time. In what historian Allen Guelzo refers to as “one of the murkiest episodes in Lincoln’s life,” Lincoln called off the wedding he and Mary had planned for January 1, 1841. He wrote to John Todd Stuart in Washington:

I am now the most miserable man living. If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would not be one cheerful face on the earth. Whether I shall ever be better I can not tell; I awfully forbode I shall not. To remain as I am is impossible; I must die or be better, it appears to me.

After Stuart won re-election to Congress in 1841, Abraham Lincoln realized that he could no longer maintain the law practice by himself, and on April 14, 1841 Stuart and Lincoln formally dissolved their partnership. After Stuart finished his second term in Congress he established a law partnership with Benjamin Edwards who was, or course, the brother of Ninian Edwards. Stuart served in Congress again in 1862 and was a frequent visitor at the White House.

On September 27, 1842, Mary and Abraham attended the same social event, and they talked for the first time since their estrangement eighteen months earlier, rekindling their love for each other. Abraham and Mary decided to marry quickly, perhaps to obstruct any further objections. Mary’s sister Frances Todd Wallace described the proceedings:

Mr. Lincoln had known my sister Mary over three years, when he called to see her the night before their marriage. He served four terms in the state legislature. He advocated sobriety, morality, and was also instrumental in establishing free schools all over the state. In his conversation with Mary, he referred to his lack of means, his ambitions, and his love for her. “I now suggest and insist upon our marriage at once. We will live at the Globe Tavern for the present. Now we must go, very quietly without fuss and feathers, at ten o’clock tomorrow morning, before the magistrate, and ask him to marry us.”

The next morning at the breakfast table, Mary told our sister Lizzie and Mr. Edwards that she and Mr. Lincoln had decided to be married at ten o’clock that morning, very quietly by the magistrate. Our aristocratic sister, with an outburst, gave Mary a good scolding. “Do not forget that you are a Todd. But, Mary, if you insist on being married today, we will make merry, and have the wedding here this evening. I will not permit you to be married out of my house.”

White House Years

Like many of Mary Lincoln’s relatives, Elizabeth Todd Edwards came to Washington for President Lincoln’s First Inauguration in March 1861. She stayed at the White House, along with her two daughters and two half-sisters, but soon returned to Illinois.

In early 1862, Willie and Tad Lincoln both became very ill, most likely with typhoid fever, which was usually contracted by consumption of fecally contaminated food or water. (This was not known at the time.) The White House drew its water from the Potomac River, along which thousands of soldiers and horses were camped. Willie died on February 20, 1862.

Both parents were deeply affected. His father did not return to work for three weeks. Mary was so distraught that Lincoln feared for her sanity. The Lincolns’ oldest son Robert sent for Elizabeth Edwards to console his mother after Willie’s death. She arrived in late February and later told Lincoln biographer William Herndon:

On the evening we strolled through [Lafayette Park] he [Lincoln] spoke of it with deep feeling, and he frequently afterward referred to it. When I announced my intention of leaving Washington he was much affected at the news of my departure. We were strolling through the White House grounds, when he begged me with tears in his eyes to remain longer.”

Elizabeth did not leave the White House until April, and a short time later Mary became incensed at Elizabeth’s daughter, Julia Edwards Baker. Elizabeth recalled that the First Lady “opened a private letter of mine after I left Washington & because in that letter my Daughter gave me her opinion of Mrs. L., she became Enraged at me. I tried to Explain – She would Send back my letters with insulting remarks.”

The Ninian Edwards Debacle

After Lincoln’s inauguration, Elizabeth’s husband Ninian Edwards, who was frequently in financial difficulty, began repeatedly asking the President for a government position, despite their political differences (Edwards was a Democrat). In August 1861, he appointed Edwards Commissary of Subsistence, whose job it was to purchase and issue provisions for the army, at Springfield, Illinois.

The President received correspondence from Illinois government officials and his Republican colleagues protesting the appointment. In July 1861, Secretary of State Ozias Hatch, State Treasurer William Butler, and State Auditor Jesse K. Dubois wrote a blistering letter to President Lincoln:

It is reported in this city, that you have written a letter to Mr. Ninian W. Edwards, in which you say, “that as soon as Congress passes the necessary laws, you will appoint him Quarter Master, to be assigned duty and attached to General Fremont’s Division.”… For several years we have been ferriting out, and exposing, the most stupendous and unprecedented frauds ever perpetrated in this country, by men closely connected with Mr. Edwards. The desperate character of this contest, and its results you know as well as we do….

Presidential aide John Nicolay reported to his boss in October 1861:

N.W. Edwards Esq, by virtue of his appointment as Brigade Commissary, has somehow obtained the superintendence of contracting for all the Commissary supplies in the State… Mr. Edwards starts for Washington to-night to obtain further authority to make all contracts of all kinds for the State, and our friends say that the whole business of furnishing the State troops, will thus fall into Gov. [Joel] Matteson’s hands*, and that this necessarily brings the Gov. into business relations with all our friends in the State, who will thus be bound to recognize and deal with him.”

*Matteson was later charged with fraud and swindling the state out $388,000.

That same month, Ninian Edwards sent a detailed letter of explanation of his activities to President Lincoln:

I am truly sorry to be the cause of adding to your perplexities, and to avoid giving any color for casting them on you, I think I had better make my arrangements to give up the office – I certainly should have never accepted it but for my very great pecuniary embarrassment. Even with it a claim was sent to a lawyer to be sued on at the next Court. There is no man living who is more conscientious in the discharge of public business than I am. I would not let the Government lose a cent if I could help it for the best friend in the world.

A barrage of complaints in May 1863 forced President Lincoln to act. Typical was a letter from his old friend Jesse Dubois in Springfield:

I have been requested by many of your oldest and most influential friends to join them in representing to you the feelings which exist here about the manner in which the Quartermaster’s and Commissary’s Departments are conducted at this place. I can only say what I have said before that the present incumbents Mess. Edwards & [Quartermaster] Bailhache ought never have been appointed and after they were appointed should never have been Stationed here.

They have given all their patronage to the enemies of your administration and have Contrived to amass fortunes with a rapidity which is a disgrace to the Government and a Scandal to its supporters. They ought to be relieved from duty here and placed where they can do no harm. You cannot afford to keep them here at the risk of alienating the affections of your neighbors and life-long friends.

To allow them to hold their present positions can result in nothing but harm to you and your administration. I have written this earnestly, because I feel so, and do not fear that you will believe me to be Actuated by any factious desire to cause you trouble or that I have any interest in this matter other than as I am your Friend and a friend of your Administration.

On May 29, 1863, Lincoln sent a letter to the thirteen Springfield Republicans who had complained about the corrupt activities of Ninian Edwards: “Agree among yourselves upon any two of your own number, one of whom to be Quarter-Master, and the other be Commissary, to serve at Springfield, Illinois, and send me their names, and I will appoint them.”

Ninian Edwards wrote to the President on June 18, 1863:

It pains me very much to hear that I give you any trouble. I know that I have not only kept my record correct, but I have taken extraordinary pains to avoid giving any cause for complaint…. When I asked an office from you… I needed it very much. I can now do without it. I don’t wish to embarrass you. If I am removed from here it will be said that there is good cause for it. Under my present orders I can keep my office at Chicago… or rather than give you further trouble I will resign. I will do what you think best.

Ninian Edwards did not resign. Lincoln replaced him as commissary in late June, but allowed Edwards to keep his office in Chicago. There is no mention anywhere as to how Elizabeth Todd Edwards felt about any of her husband’s actions.

Mary’s Insanity

Deeply traumatized by her husband’s assassination by John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865, Mary Todd Lincoln did not leave the White House until May 23, 1865. She then moved to Chicago and began to settle her husband’s estate. In 1868, Mary moved with her son Tad to Germany and lived in Europe for almost three years.

In 1871, Mary returned to the United States. The sudden death of her youngest son Tad on July 15, 1871, at age 18, left her unable to cope with life’s daily trials. According to her only surviving child, Robert Lincoln, Mary soon began to show signs of mental instability.

What he called Mary’s insanity was probably what is now recognized as bipolar disorder, which explains her alternating depressions and spending sprees. While depressed she isolated herself in a darkened room for days on end. While shopping, she was known to buy 72 pairs of gloves and expensive evening gowns she would never wear.

In 1875 Robert Lincoln successfully had his mother tried for insanity, and committed her to the Bellevue Insane Asylum, in Batavia, Illinois. Later that day, she twice attempted suicide by taking what she believed to be the drugs laudanum and camphor – which a suspicious druggist had replaced with sugar.

When Elizabeth Edwards learned of her sister’s incarceration, she wrote:

My heart rebelled at the thought of placing her in an asylum, believing that her sad case merely required the care of a protector, whose companionship would be pleasant to her. Had I been consulted, I would have remonstrated earnestly against the step taken.

One of the nation’s first women lawyers, Myra Bradwell believed Mrs. Lincoln was not insane and was being held against her will. She filed an appeal on the former First Lady’s behalf and after four months of confinement, Mary was released from Bellevue Place in September 1875 to the care of Elizabeth Edwards.

Despite their sometimes rocky relationship, Elizabeth offered Mary a home, dedicating two rooms to the storage of Mary’s 64 trunks. A second trial on June 19, 1876 declared Mary sane, and she immediately moved to France. After four years abroad Mary returned to live again in the Edwards home in October 1880.

Mary Todd Lincoln died there on July 16, 1882 at age 63. Elizabeth Todd Edwards’ death followed on February 22, 1888.

SOURCES

The Insanity File

Mr. Lincoln & Friends: Ninian Edwards

Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln

My dad was born James Sloan 1918 and had brothers Paul and John. Their father, I believe to have been named John, married a woman named Margaret (first name) known only (grandma Sloan). He told me we are related to Mary Todd Lincoln.

Is there an easy way I could find that true?