Wife of Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston

Eliza Griffin Johnston, the second wife of General Albert Sidney Johnston, was educated at a prestigious school in Philadelphia. In addition to learning social graces, she became an accomplished artist and musician. As a wife and mother Mrs. Johnston painted watercolors of birds and flowers in her free time.

Eliza Griffin Johnston, the second wife of General Albert Sidney Johnston, was educated at a prestigious school in Philadelphia. In addition to learning social graces, she became an accomplished artist and musician. As a wife and mother Mrs. Johnston painted watercolors of birds and flowers in her free time.

Eliza Griffin was born in Fair Oaks, Virginia, on December 26, 1821, to a well-to-do family. She was the youngest child and the only daughter of John and Mary (Hancock) Griffin. Eliza’s parents died when she was four years old, and she was raised by her grandmother, Margaret Strother Hancock. After her grandmother’s death in 1830, she moved to Kentucky to live with her uncle, Colonel George Hancock, and there she later met her future husband, Albert Sidney Johnston.

Eliza completed her education at a prestigious school in Philadelphia. In addition to learning the social graces, she became an artist and an accomplished musician. She was a woman of great beauty, high courage and fine talents. She also developed a familiarity with several languages, and could read and speak French fluently.

Albert Sidney Johnston, the son of John and Abigail (Harris) Johnston, was born at Washington, Kentucky, on February 2, 1803. Educated locally through his younger years, Johnston enrolled at Transylvania University in the 1820s. While there he befriended the future president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis. Davis and Johnston soon transferred to US Military Academy at West Point. Two years Davis’ junior, he graduated in 1826, ranked 8th in a class of 41. Accepting a commission as a brevet second lieutenant, Johnston was posted to the 2nd US Infantry. He served at Sackett’s Harbor, New York in 1826, and with the Sixth Infantry at Jefferson Barracks in Missouri in 1827.

On January 20, 1829, Sidney Johnston married Henrietta Preston, and they had a son, William Preston Johnston. Because of his wife’s tuberculosis, Sidney resigned his commission in the army on April 22, 1834. For more than a year, he cared for his wife and farmed near St. Louis. Henrietta died on August 12, 1835.

Johnston served as General Henry Atkinson’s chief of staff during the 1832 Black Hawk War, and was quickly recognized as a gifted officer. In 1836, he moved to Texas and enlisted as a private in the Texas Army. One month later, he was promoted to major, and aide-de-camp to General Sam Houston. On January 31, 1837, he became senior brigadier general of the entire Texas army.

In February 1837, Johnston was challenged to a duel by General Felix Huston, the man he had replaced as senior brigadier. Johnston refused to fire, but Huston shot him in the pelvis, and he was unable to take his new command. Johnston’s wound was quite severe, and it took months for him to recover. The bullet injured his sciatic nerve, which resulted in some loss of feeling in his right leg and foot. He was next appointed Secretary of War for the Republic of Texas on December 22, 1838.

In March 1840, Albert Sidney Johnston returned to Kentucky and lived there several years. He was Eliza Griffin’s cousin by marriage, and he began courting her when she was eighteen years old.

Eliza Griffin married Johnston on October 3, 1843. In November, the Johnstons went on the first of many journeys to Texas. After dividing the first two years of their married life between Texas and Kentucky, the couple and their infant son moved to Galveston. They later settled on Johnston’s plantation, China Grove, forty miles from Galveston, where they lived in a double log cabin for about three years. Two children were born on the plantation.

With the outbreak of the Mexican-American War in 1846, Sidney Johnston reenlisted in the United States Army, and raised a volunteer regiment, and was commissioned as Colonel of the First Texas Rifle Volunteers and served in Monterrey as inspector general. He saw action during the campaigns in northeastern Mexico, and on December 2, 1849, became paymaster in the United States Army and was assigned to the Texas frontier.

Unable to pay their mortgage, the Johnstons were forced to leave China Grove, and the plantation was sold at auction. The family returned to Kentucky in the spring of 1850, but moved to Texas once again when Sidney became army paymaster for the Department of Texas. They settled in Austin, and a daughter was born there.

Eliza traveled with her husband during many of his assignments throughout the Western frontier, and she developed skills as an accomplished artist. In Texas, she spent her leisure time painting watercolors of birds and flowers. She wrote, “I think myself as much of a fixture in Texas as one of its live oaks.”

Eliza kept a diary in the fall of 1854 and winter of 1855 as she traveled with her husband and his regiment – from Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, to Fort Mason on the Texas frontier, more than 700 miles away. She described the hardships of the march, camp life, foods, plants, flowers, illnesses and death. Her diary also gives clues to the personalities of many military men who would become famous in the Civil War.

Johnston went with William S. Harney to the Great Plains in 1855, and on April 2, 1856, he was appointed colonel of the Second Cavalry. In 1857, Johnston was appointed commander of a US military campaign to crush the Mormon rebellion. The Mormons had established a theocracy in Utah, and would not submit to US government when the US claimed Utah as a territory. Johnston put down the rebellion without a major conflict. In November 1860, he was promoted to brigadier general, and was given command of the Department of the Pacific, based in San Francisco.

The three-week voyage to California was rough, Eliza was seasick most of the time, and she reached San Francisco “much reduced and feeble.” But, the harrowing passage was soon forgotten in the family’s enthusiasm for their new home. The schools were good, and the climate was mild. Eliza was charmed by San Francisco, the surrounding countryside, and the demographics.

The Civil War

With the secession of Texas in early 1861, Sidney Johnston refused the federal government’s offer of a command, and resigned his commission in the United States Army. Eliza and the children had moved to San Francisco to be with him, and they moved to Los Angeles at the urging of her brother, Dr. John Griffin, a retired military surgeon who had large land holdings in the Los Angeles area. A sixth child was born there, two months after Johnston left California to join the Confederacy.

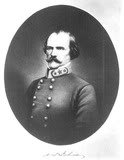

Image: General Albert Sidney Johnston

Sidney Johnston displayed the erect carriage of a professional soldier. He was tall with a deep chest, and broad shoulders. His light brown hair was graying a little, and his handsome face, deeply bronzed by the sun, was etched with wrinkles. But he looked much younger than his fifty-eight years, and he always gave off an air of total confidence. He had just completed an arduous journey of more than 3,000 miles across the continent, much of it on horseback, but he did not seem the least bit haggard.

Johnston traveled to Richmond, Virginia, where Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed him a general in the Confederate Army and assigned him to command the Western Department, in charge of Confederate operations in Tennessee and Kentucky.

General Albert Sidney Johnston took Bowling Green, Kentucky, as his base of operations, issued a call for volunteers, and worked on honing them into soldiers. His subordinate generals lost Forts Henry and Donelson on February 16, 1862, to Union Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant. Johnston has been faulted for poor judgment in selecting Brigadier Generals Tilghman and Floyd for those crucial positions and for not supervising adequate construction of the forts.

The Battle of Shiloh

CSA General P.G.T. Beauregard was sent west to join Johnston, and they organized their forces at Corinth, Mississippi, planning to ambush Grant’s forces at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee. At dawn on April 6, 1862, Johnston unleashed his attack on Grant’s unsuspecting army near a small church called Shiloh. With his corps in stacked formation, Johnston initially experienced success, pushing USA General William Tecumseh Sherman‘s division past Shiloh Church to an area known as the Crossroads. The most brutal fighting thus far in the Civil War took place just north of the Crossroads, in an area now known as the Hornet’s Nest.

By all accounts, Johnston was performing brilliantly on the field. As he encouraged his men, General Johnston rode slowly down the line. His voice was persuasive, encouraging, and compelling. His words were few: “Men, they are stubborn; we must use the bayonet.” When he reached the center of the line, he turned. “I will lead you!” he cried, and moved toward the enemy. With a mighty shout, the line moved forward at a charge.

He passed through the ordeal seemingly unhurt. His horse was shot in four places; his clothes were pierced by missiles; and his boot-sole was cut and torn by a minie ball. In the meantime, groups of Federal soldiers kept up a desultory fire as they retreated, and delivered volley after volley as they retreated.

While Johnston was leading an attack in the area of the Peach Orchard, around 2:00 pm, he was struck behind his right knee by a minie ball. Believing his injury to not be serious, he did not seek medical attention. It is possible that the injury he had received at the duel twenty-five years earlier had caused nerve damage or numbness to that leg, and that he did not feel the wound.

Within a few minutes, Johnston suddenly became very pale. One of his staff asked him, “General, are you wounded?” He answered, in a very deliberate and emphatic tone: “Yes, and I fear seriously.” These were his last words. His aides helped him dismount from his horse, and carried him to a small ravine nearby. The bullet had severed his popliteal artery, and his boot was quickly filling up with blood.

Tennessee Governor Isham Harris was an officer on General Johnston’s staff. This is his account of the incident:

I galloped back to the general, where a moment before I had left him, rode up to his right side, and said, “General, your order is delivered, and Colonel Statham is in motion;” but, as I was uttering this sentence, the general reeled from me in a manner that indicated he was falling from his horse. I put my left arm around his neck, grasping the collar of his coat, and righted him up in the saddle, bending forward as I did so, and, looking him in the face, said, “General, are you wounded?” In a very deliberate and emphatic tone he answered, “Yes, and I fear seriously.” At that moment, I requested Captain Wickham to go with all possible speed for a surgeon.

The general’s hold upon his rein relaxed, and it dropped from his hand. Supporting him with my left hand, I gathered his rein with my right, in which I held my own, and guided both horses to a valley about 150 yards in rear of our line, where I halted, dropped myself between the two horses, pulling the general over upon me, and eased him to the ground as gently as I could. When laid upon the ground, with eager anxiety I asked many questions about his wounds, to which he gave no answer, not even a look of intelligence.

Supporting his head with one hand, I untied his cravat, unbuttoned his collar and vest, and tore his shirts open with the other, for the purpose of finding the wound, feeling confident from his condition that he had a more serious wound than the one which I knew was bleeding profusely in the right leg; but I found no other, and, as I afterward ascertained, he had no other. Raising his head, I poured a little brandy into his mouth, which he swallowed, and in a few moments I repeated the brandy, but he made no effort to swallow; it gurgled in his throat in his effort to breathe, and I turned his head so as to relieve him.

In a few moments he ceased to breathe. I did not consult my watch, but my impression is that he did not live more than thirty or forty minutes from the time he received the wound. He died calmly, and, to all appearances, free from pain – indeed, so calmly, that the only evidence I had that he had passed from life was the fact that he ceased to breathe, and the heart ceased to throb. There was not the slightest struggle, nor the contortion of a muscle; his features were as calm and as natural as at any time in life and health.

General Johnston’s wound need not have been fatal. His own knowledge of military surgery was adequate enough to have saved his life by applying a tourniquet, if he had been aware of its seriousness. His personal physician, Dr. D. W. Yandell, had been with him in the morning; but when the general saw a large number of wounded men, including many Union soldiers, he had ordered Yandell to stop and establish a field hospital. He said to Yandell: “These men were our enemies a moment ago; they are prisoners now. Take care of them.” Yandell argued against leaving him, but the general insisted. Had Yandell remained with him, he would have had little difficulty controlling the bleeding.

Image: General Johnston Statue

Metairie Cemetery

New Orleans, Louisiana

General Albert Sidney Johnston died within minutes on the Shiloh battlefield on April 6, 1862, of massive blood loss. He was the highest ranking Confederate officer killed during the Civil War. Although he had not lived long enough for his leadership potential to be tested, his death was nonetheless a major loss to the Confederacy, and left a void in the leadership of the western armies that was never effectively filled.

The man whom Jefferson Davis had called the Confederacy’s finest general was laid to rest in New Orleans. In 1867, by special appropriation of the Texas Legislature, Johnston’s remains were re-interred at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin with full honors, in recognition of his service to Texas.

At the Battle of Shiloh that day, after General Johnston fell mortally wounded, command was passed to General P.G.T. Beauregard, who lost the Battle of Shiloh on April 7, when a reinforced Federal army overran his position, pushing him clear to Corinth. Thereafter, the war in the West would be dominated by the Federal armies.

General Randall Gibson wrote:

General Johnston’s death was a tremendous catastrophe. There are no words adequate to express my own conception of the immensity of the loss to our country. Sometimes the hopes of millions of people depend upon one head and one arm. The West perished with Albert Sidney Johnston, and the Southern country followed.

Eliza Johnston decided to stay in California. She bought a piece of property from her brother for $1,000, near what is today Pasadena, and brought up her family there. She named it the Fair Oaks Ranch, after her native city in Virginia and also for the stands of coast live oaks in the area.

In 1864, tragedy struck again, when Eliza’s beloved son was killed in the explosion of a boiler on the steamship Ada Hancock at Wilmington Harbor, California. Heartbroken, she sold the Fair Oaks Ranch and went home to Virginia.

In 1894, Eliza donated relics of her husband and family to the Daughters of the Republic of Texas. The donation included a book she had compiled for her husband of the watercolor paintings of Texas wildflowers she had painted in the 1840s and 1850s.

Albert Sidney Johnston Tomb

Texas State Cemetery

Austin, Texas

Eliza Griffin Johnston preserved her striking personality to the last, and continued to reside in Los Angeles until her death on September 25, 1896. Her children inherited much of her artistic talent.

Texas Wild Flowers, a book of 101 of Eliza Johnston’s paintings, was published in 1972.

SOURCES

Albert Sidney Johnston

The Johnstons of Salisbury

Georgia’s Blue and Gray Trail

General Albert Sidney Johnston

Wikipedia: Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston – CSA General

The Life of General Albert Sidney Johnston