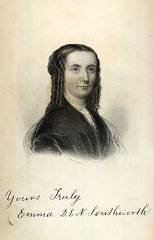

Most Popular Novelist of the Late 19th Century

E.D.E.N. Southworth (1819-1899) was the author of more than 60 novels and was the most widely read American novelist of last half of the 19th century. She invariably signed herself Mrs. E.D.E.N. Southworth, though she began writing in 1844 to support herself and her children after Mr. Southworth deserted her four years into their marriage.

E.D.E.N. Southworth (1819-1899) was the author of more than 60 novels and was the most widely read American novelist of last half of the 19th century. She invariably signed herself Mrs. E.D.E.N. Southworth, though she began writing in 1844 to support herself and her children after Mr. Southworth deserted her four years into their marriage.

Born in Washington, DC in 1819, she was christened Emma Dorothy Eliza Nevitte. Supposedly on his deathbed, her father, Captain Charles LeCompte Nevitte, persuaded a local priest to re-christen little Emma with two additional names so that her initials would spell out E.D.E.N. The acronym was well-suited to the novelist-to-be and she used it throughout her career.

Emma was born in one of the twin townhouses that Founding Father George Washington had built on North Capitol Street in Washington, DC. She would later recall that after her father’s death in 1824, her early life was filled with suffering and privation. Her widowed mother remarried, and Emma’s new stepfather, a schoolmaster, was apparently harsh and unsympathetic.

After graduating from her stepfather’s academy in 1835, Emma taught school for five years in the DC public school system. Five years later she married Frederick Southworth, an inventor from Utica, New York and moved with him to Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, then a western frontier town, living part of the time in a log cabin. She gave birth to two children: son, Richmond and daughter, Charlotte.

In 1844, when Emma was pregnant with their second child, Frederick abandoned his family to seek his fortune in South America. This was not uncommon in the 19th century. With divorce unthinkable, many men just escaped to the frontier if they wanted out of a marriage, keeping the divorce rate low, but having the same effect on those they left behind.

Faced with the task of raising and supporting her children alone, E.D.E.N. Southworth returned to Washington, DC to resume her teaching career. She wrote:

I found myself broken in spirit, health, and purse – a widow in fate but not in fact – with my babes looking up to me for a support I could not give them. It was in these darkest days of my woman’s life, that my author’s life commenced.

Her annual salary of $250 was a very meager family income. Perhaps to distract herself from her troubles, Southworth began writing fiction. She turned in a short story at a local book store she frequented, asking that it be submitted somewhere for publication. “The Irish Refugee” was published by the Baltimore Saturday Visitor in 1846.

Literary Career

Although it provided no income to its author, Southworth’s first story earned the attention of other publications, including The National Era, which published her first novel, Retribution, in serial form in 1849. That work appeared in book form later that year, and Southworth quickly became a popular writer.

Some of Southworth’s earliest works appeared in The National Era, the same newspaper that printed the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the best selling novel of the 19th century by Harriet Beecher Stowe, in 1851. Although not nearly as active as her friend Stowe and other women, Southworth was a supporter of women’s rights and social reform.

Encouraged by the enormous success of her novel Retribution, E.D.E.N. Southworth quit teaching to write full time and became a regular contributor to various periodicals. She wrote for a set amount of time each day, five days a week, for years on end, publishing twelve best-selling novels in the next seven years despite her own and her children’s recurring illnesses.

She wrote domestic novels that take place in the southern United States, mostly Virginia, during the last half of the 19th century. She wrote in segments or chapters that were first serialized in weekly newspapers, but were often reprinted in books. Serial publications enabled middle class readers to enjoy novels that would be too expensive for them to purchase as a single volume.

Southworth’s own experiences gave her sensibilities that would resonate with her female contemporaries who yearned to lead independent lives. In an era when debates over human rights dominated the political and social landscape, Southworth wrote fiction celebrating strong women who transcend or ignore class distinctions and stand firm against oppression of any sort.

As a woman repeatedly placed on the margins of society – by poverty, neglect and social stratification – Southworth learned to speak the language of the dispossessed. She believed that fiction should serve a moral purpose, and once wrote: “The novelist – the popular novelist – has a hundred-fold larger audience than the most celebrated preacher, and therefore a tremendous responsibility.”

Southworth’s ability to write quickly, steadily and copiously put her in a class all her own. Starting with her first novel, Retribution, in 1849, no woman (and, for that matter, no man) approached her cumulative record of best-selling productivity. Throughout her active career of nearly half a century, she usually wrote two substantial and successful novels every year.

The New York Ledger

In 1856, Robert Bonner of the New York Ledger recognized her appeal and prolific output and signed Southworth to a lucrative, long-term contract that paid her a generous annual salary in exchange for exclusive serial rights to her novels. Thereafter she serialized all of her novels in the Ledger before publishing them in book form.

The Ledger also featured work by Fanny Fern (Sarah Willis Parton) and other writers, but Southworth’s long novels were the paper’s main attraction, each installment running on the first page. The contract Southworth signed with Bonner and royalties from her published novels earned her $10,000 a year, making her one of the country’s best-paid writers.

Published on Saturday mornings in New York City between 1855 and 1898, the New York Ledger was the most widely read weekly paper of its time, achieving a national circulation. Its newspaper format allowed Robert Bonner to mail nationwide at cheap postal rates; the burgeoning railway network transported it to the far comers of our growing nation.

Serialization of exciting novels kept the public coming back week after week. Since each copy of the paper reached two or more readers, the actual number of Americans who read the Ledger would have been a significant percent of the country’s literate population. And to know the Ledger was to know Southworth.

Each serialization ran for approximately six months or about twenty-four weekly installments. Virtually as soon as one novel concluded, another began, so that for several decades the American public seldom lacked for a Southworth work in progress. Several of her novels were also serialized in the London Journal.

The Hidden Hand

In Southworth’s novels, her heroines often defy Victorian conventions of feminine domesticity by using wit, adventure and rebellion to improve their oppressive situations. Her most popular novel, The Hidden Hand, which was serialized in the Ledger in February 1859, is the story of the winsome and high-spirited Capitola Black who was kidnapped as a child and grew up in a New York City slum.

She is found and brought back to her ancestral Virginia home by a grumpy old uncle who intends to civilize her, but the buoyant imp will not be suppressed. In one outrageous incident, she fights a duel with a man who has slandered her and shoots the unfortunate gentleman full of dried peas.

Black secretly takes the place of an unwilling bride at a wedding ceremony and at the critical Do-you-take-this-man-to-be-your-lawful-wedded-husband moment gleefully raises her veil and cries out “No – not if he were the last man and I the last woman on earth and the human race were to become extinct – and not if the Angel Gabriel came down and asked me to do this – most certainly – No!” Readers ate it up.

This is not only the first of a long line of tomboy heroines in American fiction, but one of only a few in the nineteenth century who never relinquishes nor apologizes for her tomboy character. Southworth is also the originator of the many female action heroines, especially female detectives, who populate fiction today. The basic message is that the essence of true womanhood lies within and can never be compromised by merely unconventional behavior.

Except for her tendency to express herself in slang, and her continuing relationship with her best friend, a young sailor named Herbert Greyson, Capitola loses touch with her street associations. But the issues of womanliness and gender introduced by this opening segment of the novel continue to frame the fiction.

Throughout the novel Capitola continues to reject most rules of female decorum as humbug at best, hypocritical at worst. The author regularly attributes Capitola’s attractiveness as a character, as well as her success within the plot where other female characters fail, to her recognition of the dangers of false ideologies of true womanhood.

Like most of Southworth’s novels, The Hidden Hand contains numerous initially unconnected plots and a large cast of apparently unrelated characters, all of which mesh in the end. Undoubtedly some of the fun in reading a Southworth serialization involved waiting to see how the author would weave all these seemingly loose strands into a single pattern.

The message for women in this novel is to be more like Capitola; for men, it is to appreciate Capitola-like women. In this way, the novel contributes to the slow process of cultural change in gender norms and relations that had already manifested itself in the first women’s rights convention in the United States, held at Seneca Falls in upstate New York in 1848.

The Hidden Hand was Southworth’s sixteenth novel. By this time she had fully developed her particular novelistic abilities – ornate yet fast-paced description, rapid-fire and slang-laced dialogue (which critics especially disliked), superabundance of plot lines and characters, effective mingling of melodramatic suspense with satire – and was certain of her audience.

In 1859 E.D.E.N. Southworth was invited to visit England by her British publisher. When she arrived in London, she found “Capitola as popular there as in America. There were Capitola boats, Capitola race horses, Capitol hats for ladies and other Capitola fads.” The book was turned into a play that ran in several productions simultaneously on the London stage, including one version starring John Wilkes Booth. The novel remains in print to this day.

After spending the first two years of the Civil War abroad, Southworth returned to Georgetown in 1862 feeling “so homesick I think my heart will break.” She quickly became an outspoken supporter of the Union and served as a volunteer nurse. She was also a manager at the National Colored Home in 1863 and a volunteer at Seminary Hospital in Georgetown. She was said to have offered her cottage as a reserve hospital for convalescing soldiers.

Further, officers of the Signal Camp of Instruction later recounted that they had been entertained by the famous author at Prospect Cottage. As mentioned in Margaret Leech’s Reveille in Washington, Southworth attended Abraham Lincoln‘s second inaugural ball at the Patent Office in 1865.

Later Years

Some of Southworth’s novels were translated into German, French, Chinese and Spanish; in 1872 an edition of thirty-five volumes was published in Philadelphia. Part of Southworth’s extraordinary appeal to her contemporaries was her ability to imagine sensational or melodramatic events and adventurous, active roles for her heroines within the constraints of feminine gentility.

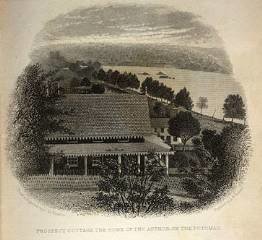

The prolific novelist with the unconventional name lived in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, DC, in a very unusual house: a picturesque cottage perched up on Prospect Street, overlooking the Potomac. It is not entirely clear when Prospect Cottage was built or even exactly when Southworth moved into it. Some say she moved there in 1860; other sources put her there as early as 1853.

Prospect Cottage was designed in the Carpenter Gothic style that was highly fashionable before the Civil War. Its gabled, deeply-overhanging roof was lined with decorative barge boards with icicle-like ornaments. Its long veranda, wrapping around the southern end of the house, offered many vantage points for appreciating the country-like surroundings or for gazing across at Virginia, where many of Southworth’s novels were set.

Charles Warren Stoddard offered this romantic description:

[T]he cottage was half hidden among the branches of the trees that embowered it and looked as cosy as a dove-cote in its airy grove. It hung upon the very brink of the hill; its lower story is below the street in the rear of it, but jutting out into a terraced garden… Its western windows were bathed in the sunset glow and the river far below it… its eastern windows opened on breezy heights where the goats skipped nimbly in a tree-filled, vacant lot; the south verandah, up among the treetops, hung like a fairy gallery before the Virginia slopes, and in the deep valley between them flowed the noble Potomac…”

Except for an extended visit with her daughter in the Hudson Valley in 1876, E.D.E.N. Southworth spent the rest of her life living and writing in Prospect Cottage, where she died in 1899 at about age 80.

Her son Richmond inherited Prospect Cottge but died the following year, leaving it to his sister Charlotte, who seems to have not had much interest in the house. Within years, it became something of a tourist trap. Today there is virtually no trace of either the house or its once-picturesque setting.

Selected Works

The Deserted Wife (1849)

The Discarded Daughter (1852)

The Missing Bride (1855)

The Broken Engagement (1862)

The Fatal Marriage (1863)

Allworth Abbey (1865)

The Changed Brides (1869)

Cruel as the Grave (1871)

Ishmael; or, In the Depths (1876)

The Bride’s Ordeal: A Novel (1877)

A Deed Without a Name (1886)

A Leap in the Dark: A Novel (1889)

The Unloved Wife: A Novel (1890)

Only a Girl’s Heart: A Novel (1893)

SOURCES

Wikipedia: E.D.E.N. Southworth

E.D.E.N. Southworth’s The Hidden Hand essay by Nina Baym

Portraits of American Women Writers: E.D.E.N. Southworth

The Prolific Mrs. E.D.E.N. Southworth and her Georgetown Cottage