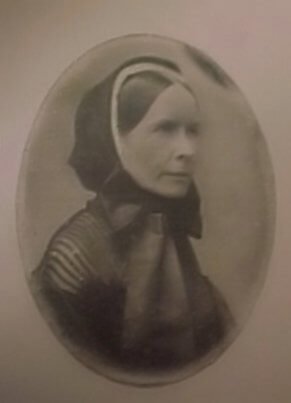

Civil War Diarist of Winchester, Virginia

Cornelia McDonald (1822–1909) was the author of A Diary with Reminiscences of the War and Refugee Life in the Shenandoah Valley, 1860-1865 in which she records her experiences during the Civil War as a woman living in Winchester, Virginia. The town changed hands numerous times during the war, and life there was uncertain at best. McDonald was among the group of women who became known as the “Devil Diarists of Winchester.”

Cornelia McDonald (1822–1909) was the author of A Diary with Reminiscences of the War and Refugee Life in the Shenandoah Valley, 1860-1865 in which she records her experiences during the Civil War as a woman living in Winchester, Virginia. The town changed hands numerous times during the war, and life there was uncertain at best. McDonald was among the group of women who became known as the “Devil Diarists of Winchester.”

Cornelia Peake was born in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1822, the youngest child of a doctor. Her father’s debts forced him to move his large family several times during Cornelia’s childhood. The family and their slaves ended up in Palmyra, Missouri, where several family members died of consumption.

Her mother died in 1837, and once again they moved, this time to Hannibal, where her older sister married Edward McDonald. His older brother Angus was an attorney and a widower with nine children. Angus was 23 years older than Cornelia, but he wooed her over the next several years, and she married him in 1847. Over the next 14 years, Cornelia gave birth to nine children: seven boys and two girls.

The McDonalds moved to Virginia, and were living in Winchester when the Civil War began. Located at the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley, the town was destined to play an important part in the war. Both of General Robert E. Lee’s invasions of the North began there. During the four years of war, the town changed hands 14 times.

The Valley was treasured for its agricultural riches, and became known as the breadbasket of the Confederate army. The area around Winchester flourished with wheat fields and lush pastures for grazing livestock.

The McDonalds lived in a large home with ample gardens on a hill overlooking the town. Angus was appointed a Colonel in the Confederate army and marched off to war with what would become the famous Stonewall Brigade, leaving Cornelia to manage the family and the household. He was 62 years old; Cornelia, 38.

In the spring of 1862, Cornelia encountered Union soldiers on her front porch. She could not keep them out, but she led the way while they searched her home. When they demanded to be shown the upstairs, she first opened her bedroom door, where all the children were gathered.

In May 1862, the First Battle of Winchester took place. General Stonewall Jackson’s division was headed north on the Valley Pike toward Winchester, where Union General Nathaniel Banks was trying to assemble his troops to stop Jackson’s advance. On May 25, the Rebels outflanked the Union position, and the Federals occupying the town fled through the streets of Winchester. Cornelia was thrilled to have her Rebels in residence.

Cornelia’s beautiful three-year-old, Bess, became very ill. There were no doctors left in town, nor any medicine available. Bess died in her mother’s arms in August 1862. After Bess was buried, Cornelia wrote, “I was lying in bed with a feeling only of indifference to everything, a perfect deadness of soul and spirit. Suddenly the house was shaken to its foundations, the glass was shivered from the windows and fell like rain all over me as I lay in bed.” When the Union army left town that night, they blew up a depot and a large magazine of gun powder.

The McDonalds owned two slaves and had always hired others from neighbors when needed. One of these was Lethea, who was a nurse to the McDonald children. Lethea’s owner sold her in October 1862, because he was afraid she would leave with the Union army, and he would lose his investment.

Cornelia wrote in her diary:

I never in my heart thought slavery was right, and having in my childhood seen some of the worst instances of its abuse, when surrounded by them and daily witnessing what I considered great injustices to them, I could not think how the men I most honored and admired, my husband among the rest, could constantly justify it, and not only that, but say that it was a blessing to the slave, his master, and his country.

Every time the Union took possession of Winchester, they tried to take the McDonald house for headquarters. Sometimes they succeeded, but at other times she appealed to the general in command and was left alone. She complained of her life during Union occupation. Yet she found decent people that helped her to the extent that they could.

Food was hard to obtain by those who would not take an oath to the Union, but Yankee soldiers violated orders and gave her packets of their food under the cover of darkness. She went hungry in order to provide nourishment for her children.

She was heartbroken watching her boys walking outside in November without shoes. Later, she wrote in her diary of the kindness of a shoemaker who sympathized with the Union cause, but made shoes for her children, knowing she had no money.

Her constant fear that Union officers would overtake her home prompted her to write in May 1863:

Today I received another intimation that my house would be wanted for a regimental hospital. I feel a sickening despair when I think of what will be my condition if they do take it. Where can I go, what can I do without home and shelter? I have had so many startling visits, and been so often summoned to surrender my house, and so often intruded upon by rude men, that if I hear a step on the porch my heart palpitates and flutters in a way to frighten me. It is often long before I can quiet its beatings. I am growing thin and emaciated from anxiety and deprivation of proper food and am weak; and now have become faint-hearted. So I fear if they make many more demands I must give up and leave all, for I do not think I can much longer continue the struggle.

In June 1863, a battle began nearby that flushed the Union troops out of the town, the Second Battle of Winchester. The fighting grew closer. Cornelia’s house became a hospital for the Confederate wounded, while the battle raged around them.

Cornelia recorded those stressful days in her diary. “Ambulances were backed up to let out their loads of wounded, and the horses reared frantic with pain from their bleeding wounds. All made an effort to crowd in there and the close atmosphere was almost suffocating. All the while the batteries thundered, and booming of cannon, the screaming of shells, and the balls of light go shooting over our heads, followed by that fearful explosion. All the weary while the children were leaning on my lap.”

Confederate forces won that battle, but soon had to retreat from Winchester. In July 1863, Cornelia decided to leave her ravaged farm. Her oldest, Harry, was big enough to help with the younger children. As they traveled south, Cornelia received notice that Angus had been a prisoner of war for quite some time, and was being released because he was ill. They left immediately for Richmond.

“Worn and emaciated, and with hair snow-white hair,” she described her husband in her diary, “he was unable to move from his chair.” They remained there for ten days, and then decided to settle the family in Lexington, Virginia, but they had no money. Cornelia sold some jewelry and managed to collect $65. She took the children to Lexington, and waited for Angus to follow when he was well enough to travel.

She was continually faced with having to break up her family, but she fought to keep them together no matter what. In Lexington, Cornelia finally hit on a stroke of luck. A gentleman there owned an empty house and wanted to rent it to someone who could teach his several children. She accepted the challenge and secured both a job and a home for her family.

In December 1863, Angus McDonald finally joined his family in Lexington to continue his recuperation, but he was greatly changed. Angus eventually returned to the Confederate army, and that was the last time Cornelia saw him alive. In May 1864, he was captured again and died several months later.

Cornelia survived the last winter of war, knowing that the end was near. She confided to her diary:

Groups of murmuring men were all around, and I first began to realize that the patience of the people was worn out; that their long suffering and endurance was to be depended on no longer; that they were beginning to see that it was of no avail to deliver the country from her enemies.

After the war, Cornelia learned that their homestead in Winchester was unusable. She and the children remained in Lexington, where she raised her children, and happily became a grandmother.