Our Nation’s Capital During the Civil War

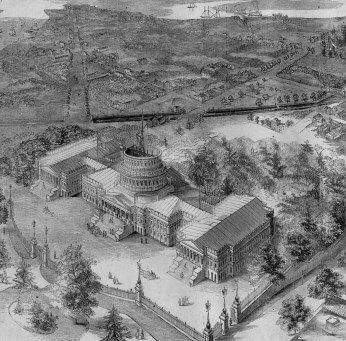

Image: Balloon View of Washington DC

Image: Balloon View of Washington DC

Note the unfinished dome on the Capitol Building

Washington Defenses

When the first inklings emerged early in 1861 that there might actually be a war between the North and South, the residents of Washington DC whose sympathies were with the Union began to feel a little threatened. By the end of April 1861, 11,000 Union troops had arrived in Washington and were put to work in late May building a series of forts and trenches. The appalling Union defeat at First Bull Run July 21, 1861, cemented the idea that a chain of fortifications around Washington was badly needed.

The man chosen to oversee the building of the defensive works around the national capital was General George B. McClellan, who took command of the Army of the Potomac July 27, 1861 and immediately stepped up the building projects. McClellan began by drawing up a complete ring of forts and entrenchments 33 miles long. Margaret Leech, author of Reveille In Washington (1942), wrote:

The chaos of Washington inspired McClellan to an almost frenzied activity. Convinced that the city was about to be attacked by an overwhelming force, he spent twelve and fourteen hours a day on horseback, and worked at his desk until early morning.”

By the end of 1862, fifty-three forts and twenty-two artillery batteries encircled virtually the entire city, from the northwest banks of the Potomac River all the way around to the river’s shoreline opposite Alexandria, Virginia. Rumors flew throughout the war of pending attacks on Washington. The weakest links in the chain were the forts in Northwest Washington and on the Virginia side of the Potomac.

The main concern was an attack or raid by the famed Confederate guerrilla leader Colonel John Singleton Mosby, known as the Gray Ghost, whose men conducted hit-and-run operations throughout Northern Virginia. There were more than a few scares, but the capital was never seriously threatened throughout the war.

Slaves, Freedmen and Freedwomen

Before the Civil War, Washington was home to a growing number of free blacks who worked as skilled craftsmen, hack drivers, businessmen and laborers. There were also enslaved African Americans and slave auctions were held in the city until they were outlawed in 1850. Slaves living in Washington were emancipated on April 16, 1862, nine months before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863.

Elizabeth Keckley, former slave and dressmaker to First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln, was well settled in Washington society by the time the Civil War began, but she feared for other African Americans who crowded into the city. Keckley wrote in her memoir, Behind the Scenes:

They came with a great hope in their hearts, and with all their worldly goods on their backs. But the North is not warm and impulsive. The bright joyous dreams of freedom to the slave faded – were sadly altered in the presence of that stern, practical mother, reality. Poor dusky children of slavery … the transition from slavery to freedom was too sudden for you.

Domestic, governmental and service jobs attracted African Americans from Maryland and Virginia, where restrictions were greater. But in 1861, free blacks in DC still had to navigate past slave pens, and slave catchers patrolled Washington for fugitives. Free blacks still had to prove their free status by carrying certificates of freedom at all times. They were required to enter into bonds with five respected members of the community who were willing to vouch for their good behavior.

Image: North Side of the White House

Photograph taken during the Civil War

By the end of 1861, conditions in the capital had become extremely difficult. Fugitives from Southern states were arriving without housing, jobs or money. While the city was wrestling with the problem of caring for them, fugitive slaves from Maryland were being hunted down and locked up, because federal law still protected slavery in states loyal to the Union. Antislavery members of Congress protested loudly the treatment of Maryland slaves and received support from the Northern press.

A movement for emancipation took hold. In January 1862, Thaddeus Stevens, Republican leader in the House, called for emancipation of DC slaves, arguing that forcing the loss of enslaved labor would ruin the rebel economy. Over the objections of the Washington city council, Congress declared that all slaves in the District were freed April 10, 1862 – and the federal government compensated the owners.

The government organized camps to provide shelter for these freedpeople, who were called contrabands of war. In an appeal to Northern sympathizers published in September 1862 in a Boston abolitionist newspaper called The Liberator, former slave Harriet Jacobs reported the conditions in the city:

I went to Duff Green’s Row, government headquarters for the contrabands here. I found men, women and children all huddled together without any distinction or regard to age or sex. Some of them were in the most pitiable condition. Many were sick with measles, diptheria, scarlet or typhoid fever. Some had a few filthy rags to lie on, others had nothing but the bare floor for a couch. … Some of them have been so degraded by slavery that they do not know the usages of civilized life: they know little else than the handle of the hoe, the plough, the cotton pad, and the overseer’s lash.

True freedom would be a long time (if ever) coming for African Americans in Washington. Whites feared they would take their jobs; they fought against giving rights to freedpeople. Racial prejudice, if possible, was stronger than ever. A large African American population remained after the war who created vibrant communities and fought racial segregation and injustice.

Rose O’Neal Greenhow

A pillar of antebellum Washington society, wealthy widow Rose O’Neal Greenhow befriended both Northerners and Southerners, including Senator John C. Calhoun, President James Buchanan, and William Seward. Despite her strong Southern sympathies, she entertained Union officers and Republican politicians at her home in an effort to discern any information that she could provide to the South.

She moved in important political circles and cultivated friendships with presidents, generals, senators, and high-ranking military officers, using her connections to pass along key military information to the Confederacy. In early 1861, she was given control of a pro-Southern spy network in Washington, DC.

On August 23, 1861, Union officials, who had been tracking her espionage activities, placed Greenhow under house arrest. On January 18, 1862, she was transferred to Old Capitol Prison, which housed both Confederate and Union prisoners as well as prisoners of state. Her eight-year-old daughter Little Rose was permitted to remain with her. On May 31, 1862, Greenhow and her daughter were released from prison.

Running the blockade, Greenhow sailed to Europe to represent the Confederacy in a diplomatic mission to France and England from 1863 to 1864. While there, she wrote and published her memoirs, My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington (1863), which cemented her place in the annals of Civil War history.

On her return voyage to America in September 1864, her ship, a British blockade runner, ran aground at the mouth of the Cape Fear River near Wilmington, North Carolina. Fearing capture and re-imprisonment, Greenhow fled on a rowboat, but it was capsized by a wave. Greenhow drowned, weighed down with $2,000 worth of gold from her memoirs royalties intended for the Confederate treasury. She was honored with a Confederate military funeral.

Eyewitness to Tragedy

Dr. Charles Leale was a newly appointed 23-year-old Assistant Surgeon in the U.S. Army Volunteers and had just received his medical degree six weeks earlier. Union medical officials had assigned Leale to the General Hospital at Armory Square [link] in Washington, DC, where he was serving as the surgeon in charge of the Wounded Commissioned Officers’ Ward.

When he heard that President Lincoln would be at the April 14 performance of the play Our American Cousin, Leale decided to attend as well. Leale, seated only 40 feet from the presidential box, was enjoying the performance when he suddenly heard a gunshot, and then saw John Wilkes Booth leap from the box onto the stage. Then someone shouted that the president had been murdered, and Leale ran to the box and found Lincoln unconscious, breathing intermittently, with no discernible pulse.

Image: Death of Lincoln

Image: Death of Lincoln

By Alexander Ritchie

Library of Congress

Dr. Leale examined Lincoln’s head, “and soon passed my fingers over a large firm clot of blood situated about one inch below the superior curved line of the occipital bone.” Removing the clot of blood, Leale discovered a hole in the skull and found that a bullet had penetrated the skull and entered the brain. A slight oozing of blood flowed from the hole, and Lincoln’s breathing suddenly became easier.

Lincoln’s brain had been swelling due to the accumulation of blood caused by the injury. The increased pressure within his enclosed skull was compressing the brain and interfering with his respiratory functions. By removing the clot, Leale had reduced the pressure in the brain, but the slain president did not ever regain consciousness.

Leale wrote in his book, Lincoln’s last hours (1909):

Many looked on during these earnest efforts to revive the President, but not once did any one suggest a word or in any way interfere with my actions. Mrs. Lincoln had thrown the burden on me and sat nearby looking on. … I then pronounced my diagnosis and prognosis: “His wound is mortal; it is impossible for him to recover.”

This message was telegraphed all over the country.

Dr. Leale then decided that President Lincoln should be moved to the nearest house and made as comfortable as possible. Leale was sure the carriage ride to the White House would kill him. Lincoln was carried from the theater to the Petersen house across the street, where Dr. Leale continued to monitor his condition.

As the night hours dragged by, Mary Todd Lincoln [link] was allowed to come into the room. Excerpt from Leale’s Lincoln’s last hours (1909):

As Mrs. Lincoln sat on a chair by the side of the bed with her face to her husband’s his breathing became very stertorous and the loud, unnatural noise frightened her in her exhausted, agonized condition. She sprang up suddenly with a piercing cry and fell fainting to the floor. Secretary [of State Edwin] Stanton hearing her cry came in from the adjoining room and with raised arms called out loudly: “Take that woman out and do not let her in again.” Mrs. Lincoln was helped up kindly and assisted in a fainting condition from the room. Secretary Stanton’s order was obeyed and Mrs. Lincoln did not see her husband again before he died.

Dr. Leale meticulously recorded Abraham Lincoln’s final hours. At 7:20 am April 15, 1865, our beloved president took his last breath.

Dr. Charles Leale later recorded his last thoughts as he left the Peterson house after Lincoln’s death:

I left the house in deep meditation. In my lonely walk I was aroused from my reveries by the cold drizzling rain dropping on my bare head, my hat I had left in my seat at the theatre. My clothing was stained with blood, I had not once been seated since I first sprang to the President’s aid; I was cold, weary and sad. The dawn of peace was again clouded, the most cruel war in history had not completely ended.

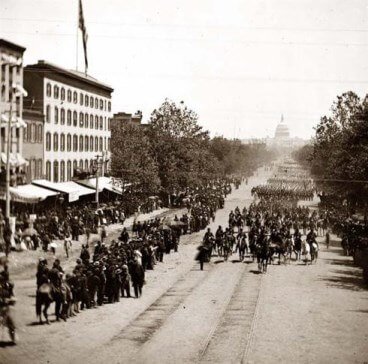

Grand Review of the Armies

On May 23 and 24, 1865, Washingtonians witnessed the momentous Grand Review of the Armies in Washington, DC. The Army of the Potomac paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue past crowds that numbered into the thousands, with their commander, General George Gordon Meade. From a reviewing stand in front of the White House, General Ulysses S. Grant and senior military leaders saluted the troops, alongside President Andrew Johnson and governmental officials.

Image: Grand Review of the Armies

Image: Grand Review of the Armies

Washington, DC, May 1865

Note the completed Capitol Dome

The following morning at 10 o’clock, General William Tecumseh Sherman led the 65,000 men of the Army of the Tennessee and Army of Georgia, who had marched 250 miles to arrive in time for the parade. The experience made a deep impression on poet Walt Whitman, who wrote about the return of the heroes in his autobiography, Specimen Days:

For two days now the broad spaces of Pennsylvania avenue along to Treasury hill, and so by detour around to the President’s house, and so up to Georgetown, and across the aqueduct bridge, have been alive with a magnificent sight, the returning armies. In their wide ranks stretching clear across the Avenue, I watch them march or ride along, at a brisk pace, through two whole days – infantry, cavalry, artillery – some 200,000 men. Some days afterwards one or two other corps; and then, still afterwards, a good part of Sherman’s immense army, brought up from Charleston, Savannah…

Within a week of the celebrations, the armies were disbanded and many of the volunteer regiments and batteries were mustered out of the army. The return home of fathers, brothers, and sons signaled to the population at large that the American Civil War had finally come to an end.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Rose O’Neal Greenhow

Lincoln’s Last Hours by Dr. Charles Leale

Wikipedia: Grand Review of the Armies

Capital Defense – Washington DC in the Civil War

Grand Review of the Armies, Washington, DC, May 1865

For freed blacks in the Civil War, Washington was a city of contradictions