Union Military Hospitals in a Southern Town

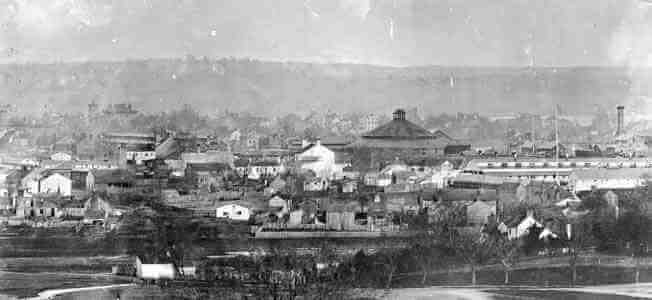

Image: Photograph of Alexandria, Virginia during the Civil War

Credit: Library of Congress

On May 24, 1861, Union troops crossed the Potomac River and occupied Alexandria, Virginia – from the first days of the Civil War to the last. This occurred just one day after its citizens had voted to have their state join the Confederacy. Alexandria was the first Southern city to be occupied by Northern troops.

Inadequate Medical Care

When the Union and Confederate armies clashed on the fields near Manassas, Virginia in July 1861, the opposing sides had made few preparations to care for the wounded. When the routed Union Army came running back to Alexandria, no doctors or hospitals were waiting to tend to the one thousand men who had been injured. Civilians and local officials criticized the Army’s poor treatment of the wounded and called for a system that would ease the suffering of the soldiers.

The Civil War took place just prior to the development of germ theory by European doctors; therefore, medical professionals were unaware that instruments should be sterilized and wounds should be properly cleaned. Various infections coursed through the wards, as well as contagious diseases like typhoid fever. The spread of disease in hospital wards and army camps caused two-thirds of the deaths during the Civil War.

Amputations frequently occurred because it was the safest procedure for men who had been shot in the extremities. The powerful Minie Ball used in most weapons splintered bone beyond repair. Amputation allowed for a faster, safer recovery and could lessen the chances of death by serious infection.

Old Hallowell School Hospital

The Hallowells were a Quaker family noted for their contributions to education. In 1824, Benjamin Hallowell founded a preparatory school in Alexandria, where he also gave evening lectures to adults and private lessons to girls. By 1830 the Alexandria Boarding School was successful, with many students from the families of Congressmen, Cabinet members, and other prominent citizens. Robert E. Lee was one of those students.

Image: Old Hallowell School

Image: Old Hallowell School

First building converted into a hospital

The building served as a school from 1832 until the Surgeon General designated it as a hospital after the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. It was called the Old Hallowell School Hospital and was eventually expanded to five structures. The main hospital on North Washington Street connected by a long narrow walkway to a building on N. Columbus Street. Two wooden barracks ran parallel to Cameron Street. A dead house was located on N. Columbus Street.

Civil War Hospitals in Alexandria

The Union Army used the town as a base for supplies, troop transfer, and an important center for the care of the wounded and sick. Churches, homes, and other buildings were used as medical facilities. Surgeons, nurses, relief workers, ambulance drivers, and volunteers came to Alexandria to care for the wounded. It soon became obvious that many more medical facilities were needed in Alexandria. Capt. J.G.C. Lee, the quartermaster for a good part of the war, later recalled:

By rail at first, and afterward by steam boat, they [the wounded] poured in. The first telegram received by me from the commanding general read, “Send to the front three carloads of ice. Prepare to care for ten thousand wounded.”

New hospital complexes were built according to plans drawn up by the Quartermaster-General in Washington; they featured long, ventilated barracks in which patients were divided into wards. Military officials established more hospitals as they were needed.

Mansion House Hospital

The Mansion House Hotel, operated by Confederate sympathizer James Green, was considered one of the premier luxury hotels on the East Coast. In early November 1861, Green received a letter from Union officials that they intended to use his hotel as a hospital and he had three days to vacate the premises. The Mansion House Hospital was opened December 1, 1861 as a General Hospital – not assigned to any specific unit in the Union Army. With 500 beds, it was the largest of the confiscated buildings used as military hospitals in Alexandria.

Image: Mansion House Hospital

Image: Mansion House Hospital

The hospital became a battleground between doctors who oppose women working in hospitals and young women from the North and the South who were determined to be accepted as nurses. Surgeon J.B. Porter felt he had been falsely accused of misdeeds by patients at the hospital, and he requested a hearing before a Court of Inquiry, as reported in the New York Times on March 22, 1862:

General Orders No. 85 – The Court find that certain inmates of Mansion House Hospital at Alexandria, Va., furnished by Col. J.H. Mansfield, agent of the State of Wisconsin and Aide-de-Camp to the Governor of said State, certain letters alleging certain matters against Surgeon J.B. PORTER, USA. … The Court took these letters as the basis of their inquiry and, on the evidence, under oath of the complainants themselves, the evidence has failed to substantiate the statements set forth in these letters. … No witness has testified to Dr. PORTER’s striking patients, or otherwise punishing them. … The Court finds that the conduct of Dr. John B. PORTER towards the patients has been distinguished by kindness and consideration for the wants of the sick. …

In the summer of 1865, following the surrender of Confederate troops, the mansion and hotel were returned to James Green. A local diarist wrote that the Union Army, “after abusing it most shamefully left the premises in such disorder, as to require great repairs and months of cleaning.” Green reopened his hotel but after his death in 1880, the property slid into disrepair and passed through the hands of several owners.

Image: Nurse Clarissa Jones

Image: Nurse Clarissa Jones

Nurse at Downtown Baptist Church Hospital

Credit: National Museum of Civil War Medicine

Frederick, Maryland

Camp Convalescent

This Camp was established to shelter the men who were not well enough to rejoin their regiments but not ill or wounded enough to occupy a hospital bed full time. Nurse Amy Bradley, Special Relief Agent for the U.S. Sanitary Commission was assigned to this hospital, often called Camp Misery, in December 1862.

Miss Amy Bradley had entered the Civil War as a nurse with the 5th Maine Regiment. It was soon recognized that her efficiency and skills were excellent, and she assumed more responsibility in the wards. When the Maine troops moved south to the Virginia Peninsula, Bradley offered to work for the Sanitary Commission. She served aboard the Ocean Queen, and then in Washington DC until December 1862, when she was asked to go to Camp Convalescent at Alexandria.

Excerpt from Women’s Work in the Civil War: A Record of Heroism, Patriotism, and Patience by L.P. Brockett and Mary Vaughn (1867):

Numerous attempts had been made to improve the condition of the camp [Camp Convalescent], but owing to the small number and inefficiency of the officers detailed to the command, it had constantly grown worse. The convalescents, numbering nine or ten thousand, were lodged, in the depth of a very severe winter, in wedge and Sibley tents, without floors, with no fires, or means of making any, amid deep mud or frozen clods, and were very poorly supplied with clothing, and many of them without blankets.

Under such circumstances, it was not to be expected that their health could improve. The stragglers and deserters and the new recruits were even worse off than the convalescents. The assistant surgeon and his acting assistants, up to the last of October 1862, were too inexperienced to be competent for their duties.

… In December, 1862, while the men were yet in Camp Misery, Miss Bradley was sent there as the Special Relief Agent of the Sanitary Commission, and took up her quarters there. … She arrived on the 17th of December, and after setting up her tents, and arranging her little hospital, cook-room, store-room, wash-room, bath-room, and office, so as to be able to serve the men most effectually, she passed round with the officers, as the men were drawn up in line for inspection, and supplied seventy-five men with woolen shirts, giving only to the very needy. In her hospital tents she soon had forty patients, all of them men who had been discharged from the hospitals as well; these were washed, supplied with clean clothing, warmed, fed and nursed.

Others had discharge papers awaiting them, but were too feeble to stand in the cold and wet till their turn came. She obtained them for them, and sent the poor invalids to the Soldiers’ Home in Washington, en route for their own homes. From May 1st to December 31st, 1863, she conveyed more than two thousand discharged soldiers … to the Commission’s Lodges at Washington; most of them men suffering from incurable disease, and who but for her kind ministrations must most of them have perished in the attempt to reach their homes. In four months after she commenced her work she had had in her little hospital one hundred and thirty patients, of whom fifteen died. …

On the 8th of February, 1864, the convalescents were, by general orders from the War Department, removed to the general hospitals in and about Washington. … For nearly two months Miss Bradley was confined to her quarters by severe illness. On her recovery she pushed forward an enterprise on which she had set her heart, of establishing a weekly paper … to be called The Soldiers’ Journal, which should be a medium of contributions from all the more intelligent soldiers in the camp, and the profits from which (if any accrued), should be devoted to the relief of the children of deceased soldiers. On the 17th of February the first number of The Soldiers’ Journal appeared, a quarto sheet of eight pages; it was conducted with considerable ability and was continued till the breaking up of the … hospital, August 22, 1865, just a year and a half. The profits of the paper were twenty-one hundred and fifty-five dollars and seventy-five cents. …

Downtown Baptist Church Hospital

When the Downtown Baptist Church was taken for use as a hospital on July 5, 1862, The Philadelphia Press reported that Reverend Bitting, pastor of the church, was in trouble with the provost marshal. This article from the Press (Monday, July 21, 1862) explains – somewhat:

A PHILADELPHIA MINISTER IN TROUBLE

We learn that Rev. Mr. Bitting, formerly of this city, who is now pastor of the Baptist Church in Alexandria, Virginia, was lately informed by Colonel Gregory, the provost marshal of that place, that if he could not pray for the President of the United States and the success of the Federal arms, he would be compelled to close his church.The reverend gentleman asked until the next morning to consider the subject, which was granted by Colonel Gregory. Mr. Bitting, in company with the mayor of Alexandria, called upon Colonel Gregory, and informed him that he could not comply with his request. Colonel Gregory replied that he (Mr. Bitting) being a Philadelphian and a minister of the Gospel of Christ, and an instructor of the people in righteousness, it was certainly incumbent upon him to lead them in the way which would produce peace and good order, and that the only object of the Government was to restore order, and bring back peace to our distracted country.

Mr. Bitting replied that he had made it a rule not to interfere with politics, and had endeavored to preach the Gospel. Colonel Gregory informed him that politics had nothing to do with the matter; that the subject had resolved itself into the question of a Government or no Government, and that he who was not for the Government must be against it.

Occupying the position which he did, and being from the loyal State of Pennsylvania, he was extremely sorry that he had placed himself in a position which forbid him to pray for the President and thank God for the success of the Federal arms. This being the case, he must take military possession of the church, which was immediately done by the adjutant.

Clarissa Jones, head nurse at the Baptist Church hospital in Alexandria, wrote the following excerpt in a letter:

We have 9 Sesesh prisoners in the Church opposite to which we belong, being under the same officers, etc. Certain females come daily with grapes, peaches & the like to give to them [Confederate POW patients] alone – that is not allowable, for all the good things sent to the institution are equally divided, and this we explain, but not to their satisfaction. They become terribly worked up and in a majority of cases go off with their contributions. They do not understand what it is to be lady-like in their conversation or behavior. We have a [United States] flag over the door now to keep them out; they have a holy horror of the article and even to attend to their own sick will hardly subject themselves to the degradation of coming under it.

Tuscan Villa Hospital

The Tuscan Villa had been built in the Italianate style that became popular in the United States in the earlier part of the 1800s. This house was the large private residence of Francis L. Smith, who is known for acting as Robert E. Lee’s attorney in his unsuccessful attempt to regain possession of Arlington House. The Tuscan Villa was confiscated for use as a branch of the Wolfe Street Hospital, which was the Division I General Hospital.

From a letter written by aid worker Julia Wilbur, a Quaker woman from upstate New York who came to Alexandria as a Freedmen’s Aid worker, on Christmas Eve 1862:

You at a distance cannot image what a place this is at present. It was last Friday that 700 wounded were brought here. All day long the ambulances were busy in moving them from the boats to the hospitals. A great many slightly wounded were able to walk and will soon be well. In one hos[pital] I saw one ward filled up. Their wounds had been well dressed and they said they were well cared, they have plenty of blankets, and they were moved just as carefully as could be and laid on those clean white beds as tenderly as it c[oul]d have been done at home. … Among all those wounded, suffering men, I heard not a groan nor a complaint.

Image: Tuscan Villa Hospital

Image: Tuscan Villa Hospital

Photograph by Matthew Brady

By the end of the Civil War, more than thirty Federal hospitals and 6,500 sick beds were located in Alexandria.

SOURCES

Mercy Street PBS: Welcome to a Civil War Hospital

Alexandria During the Civil War

Union Hospitals in Alexandria

Extraordinary Alexandria: Mercy Street

A Look Inside the Union Occupation of Alexandria and the Peninsula Campaign