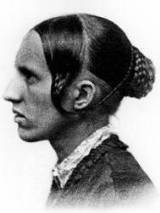

Author and Women’s Rights Activist

Caroline Wells Healey Dall was an author, journalist, lecturer and champion of women’s rights. A feminist and Unitarian Church liberal, Dall played a significant role in the antislavery movement and as spokesperson for woman’s access to education and employment.

Caroline Wells Healey Dall was an author, journalist, lecturer and champion of women’s rights. A feminist and Unitarian Church liberal, Dall played a significant role in the antislavery movement and as spokesperson for woman’s access to education and employment.

Caroline Healey was born on June 22, 1822, the oldest of eight children born to wealthy Bostonians, Mark and Caroline Foster Healey. Her father was a successful merchant, banker and investor in railroads who taught 18-month-old Caroline to pick out letters from the large type on the front page of the Christian Register.

At a time when most parents did not take girls’ education seriously, Mark Healey insisted on the best possible education for his daughter. Taught by tutors and at Joseph Hale Abbot’s School for Girls, Caroline began writing at an early age. In her early teens she wrote articles for the Christian Register and other newspapers, some of which she included in her first book, Essays and Sketches (1849).

Between ages 13 and 15 Caroline studied Latin, French and Italian. Due to her mother’s illness, Caroline took charge of the Healey household from the age of thirteen, and her formal education ceased at fifteen, but her thirst for learning did not. She learned, from Harvard professor Edward Tyrell Channing’s comments on his students’ papers, how to polish the style of her writing.

By 1840 Caroline was working in programs to assist Boston’s working-class poor. She taught Sunday school at the Benevolent Fraternity’s Pitts Street Chapel, ran a nursery for children of working women, and served as a visitor to the poor in their homes.

In 1840 18-year-old Caroline began visiting Elizabeth Peabody‘s new bookstore in Boston, and was greatly impressed by Peabody. Here was a model for womanhood quite different from her mother’s example. She wrote in her journal, “I love to hear her talk, to see her smile – although I return from both amazingly humbled in my own conception.”

In 1841 Peabody persuaded Caroline, a generation younger than most participants, to attend Margaret Fuller‘s weekly Conversations. Fuller, once precocious and outspoken herself, was repelled by the younger woman’s assertiveness. Dall later credited her association with Fuller as opening for her “all the great questions of life.”

In 1842, with her father facing bankruptcy, Caroline moved to Georgetown in the District of Columbia to work as the vice-principal at Miss English’s School for Young Ladies, a position she held for two years. She was also involved in founding a school for free African-Americans, a controversial and unpopular idea in Washington’s pro-slavery social circles.

Marriage and Family

While in Georgetown, Caroline became reacquainted with Charles Henry Appleton Dall, a Unitarian minister from Baltimore and a graduate of the Harvard Divinity School whom Dall had first met in Boston in 1837. Despite the misgivings expressed in her diary, Caroline married Dall on September 24, 1844.

Thus began what would be a tumultuous life over the next several years as the Dalls moved from one ministerial posting to another. Between 1846 and 1854 Charles Dall was assigned to churches in Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Needham, Massachusetts; and Toronto, Ontario. The couple had two children, William Healey Dall (born in 1845) and Sarah Keene Healey Dall (born in 1849).

During this time, Caroline helped Charles with his parish work, taught classes and sometimes even preached. She also continued to write, and was corresponding editor of pioneering women’s rights magazine, The Una, published by Paulina Wright Davis. While in Toronto (1850-1854) Caroline worked with an organization that helped fugitive slaves escape to Canada.

In her book Essays and Sketches (1849) Caroline Dall declared education to be “every woman’s birthright,” along with the right to find gainful employment. She claimed as woman’s “legitimate inheritance” the privilege of preaching, the respect of men, and freedom from being considered “a tool or a plaything.”

Unfortunately, Charles Dall turned out to be unstable. His tendency to stay in bed when faced with criticism limited his progress in the ministry, and he became a financial and emotional burden to Caroline. While they were in Toronto, he suffered a major breakdown, his ministry ended in professional and physical disaster in 1854, and the family returned to Boston.

In 1855 Charles Dall accepted an appointment by the American Unitarian Association as the first missionary to Calcutta, India, abandoning Caroline and their two children, ages five and nine. From then until his death in July 1886, Charles lived in Calcutta, briefly returning to the United States only five times in 31 years.

Caroline Dall remained in Boston and raised their children on her own, becoming increasingly involved in abolitionist and women’s rights activities. She was not without financial resources, however. By this time her father was a multi-millionaire, but Caroline was determined to make her own way, and made her living as a lecturer.

At the ninth National Women’s Rights Convention in New York City on May 12, 1859, speeches were given by Lucretia Mott, Antoinette Brown Blackwell and Ernestine Rose. Caroline Dall read the resolutions including one intended to be sent to every state legislature, urging that body to “secure to women all those rights and privileges and immunities which in equity belong to every citizen of a republic.”

Overbearing by nature, Caroline Dall soon alienated other leaders of the women’s movement, and her somewhat abrasive manner made her an unlikely candidate for a leadership role in “cooperative undertakings.” On the other hand, she found it difficult to work with other strong women and eventually dropped out of the organized women’s movement. Consequently, her contributions to women’s suffrage were neglected by later historians.

Feminist Author

Dall then turned exclusively to writing and speaking, and publishing several collections of her lectures. She produced a variety of works including Historical Pictures Retouched (1859), Barbara Frietchie (1892), and other notable historical writings; and the Patty Gray children’s stories (1869). She also published a score of articles, columns and reviews in the Springfield Republican, the Cambridge Tribune, the Nation and other periodicals.

In the 1860s Dall began publishing books on women’s rights, including Woman’s Right to Labor; or, Low Wages and Hard Work (1860) and Woman’s Rights Under the Law (1861), both significant feminist tracts. Woman’s Right to Labor deals with such issues as prostitution and the economic circumstances that lead women to it; factory work and its oppressive environment; women and self-employment; the ghettoization of women into traditional female occupations; female child laborers; and women’s role in the global economy.

Excerpt from Woman’s Right to Labor:

I ask for woman, then, free, untrammelled access to all fields of labor; and I ask it, first, on the ground that she needs to be fed, and that the question which is at this moment before the great body of working women is death or dishonor: for lust is a better paymaster than the mill-owner or the tailor, and economy never yet shook hands with crime.

It is pretty and lady-like, men think, to paint and chisel: philanthropic young ladies must work for nothing, like the angels. Let them, when they rise to angelic spheres; but, here and now, every woman who works for nothing helps to keep her sister’s wages down… Why? Because she helps to depress the estimate of woman’s ability. What is persistently given for nothing is everywhere thought to be worth nothing.

What many consider Dall’s most important written work, The College, The Market, and the Court: or Woman’s Relation to Education, Labor, and Law, (1867) grew out of the lectures she gave in Boston (1859-1862), in which she called for coeducation, equal vocational opportunities, equal pay for equivalent work, equality of the sexes under the law, and an equal share in the making of laws, which entailed the enfranchisement of women.

In this work, Dall argued that only work would give women the full human dignity they deserved. She described capable and educated middle-class women as underemployed and frustrated, and the lack of access to a livelihood as nothing less than tragic for women of the laboring class. According to Dall, many were driven to prostitution to feed themselves and their children.

In 1865 Dall helped found the American Social Science Association, an organization for helping the poor, unemployed, imprisoned and mentally ill, and served on its executive committee for the next forty years. During that time she worked for improvements in prison conditions, the treatment of the insane, public health and education.

After Mark Healy died in 1876, Dall lamented that in his last decade her father had squandered his fortune with ill-advised investments. Although their relations were always affectionate, the two had quite different personalities. They often found each other’s ideas and actions mutually incomprehensible. Dall wrote of her father shortly after his death:

I have thanked him every day of my life for [my] education, and if when the times came which tried men’s souls, he found it impossible to bear the results of his own loving and strenuous effort, who shall blame him? He was only one of thousands, and in the world which is to come, there will be no shadow between our souls.

In 1879 Caroline Dall moved to Washington, DC, where she taught adult classes in literature and morals and was a friend of First Lady Frances Cleveland. She lived there with her son, naturalist William Healey Dall, who had studied and published extensively on mollusks, and participated in the United States Coastal Survey of Alaska and the U.S. Geological Survey. He had also been a curator at the Smithsonian Institution since 1869.

Late Years

Dall continued to publish works of non-fiction for adults on such varied topics as The Romance of the Association; or, One Last Glimpse of Charlotte Temple and Eliza Wharton (1875), What We Really Know About Shakespeare (1885), and two autobiographical works – My First Holiday; or, Letters Home from Colorado, Utah and California (1881) and Alongside (1900), the latter, an account of her childhood.

Late in life Dall took on the role of historian of the Transcendentalist movement, publishing Margaret and Her Friends (1895), a book based on her notes of Margaret Fuller’s Conversations in 1841. This account, and her lecture Transcendentalism in New England (1897), challenged the accepted treatment of the Transcendentalists written by Octavius Brooks Frothingham two decades earlier, criticizing Frothingham’s neglect of Henry David Thoreau and Frederic Henry Hedge.

Dall made light of German philosophers’ influence on the movement and claimed instead that it was an indigenous product of New England’s history. She proposed Puritan dissident and martyr Anne Hutchinson as Ralph Waldo Emerson‘s spiritual ancestor. Although she had once herself admired him, she dismissed Bronson Alcott for his gross irresponsibility towards his family, as a figure unworthy of attention.

Also, unlike any previous writer, Dall insisted on two points: that the Transcendentalist movement was much more a movement for practical social reform than an episode in the history of ideas, and that Fuller and other women were not peripheral to the movement, but central players. Dall’s assertions substantially affected the way later historians would write of the Transcendentalists.

Though apparently troubled by chronic poor health, Caroline Dall was quite active until her death of pneumonia on December 17, 1912, at age 90.

From the age of fifteen until almost ninety, Dall documented in her journal her extraordinary life as a well educated woman, as the wife of a struggling minister, then as a single parent, struggling to turn her talents into economic rewards, and finally as a major reformer. This diary, perhaps the fullest record of a woman’s life in 19th century America, is part of the large Caroline Dall Papers collection at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

SOURCES

Caroline Wells Healey Dall

Caroline Dall and her Extraordinary Diary