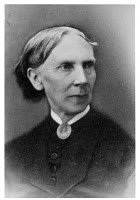

Philanthropist and Reformer During the Civil War

Annie Wittenmyer’s husband died shortly before the Civil War began, leaving her considerable wealth, and enabling her to become one of America’s foremost women reformers. After becoming secretary of her local Soldiers’ Aid Society, she launched a statewide system of collecting and distributing hospital supplies. After the war, she lobbied Congress for a bill that would grant pensions for former Civil War nurses.

Annie Wittenmyer’s husband died shortly before the Civil War began, leaving her considerable wealth, and enabling her to become one of America’s foremost women reformers. After becoming secretary of her local Soldiers’ Aid Society, she launched a statewide system of collecting and distributing hospital supplies. After the war, she lobbied Congress for a bill that would grant pensions for former Civil War nurses.

Born on August 26 1827, in Sandy Springs, Ohio, Annie Turner later became a Civil War nurse and relief worker. She married William Wittenmyer in 1847. In 1850, they moved, with his eleven year-old daughter Sally Anne to Keokuk, Iowa.

When Annie arrived at Keokuk, there were no public schools in the town. A schoolhouse was being built but it was not finished. In 1853, Annie hired a teacher and opened a free school for two hundred children. Her school continued until the public school opened. Annie gave birth to five children, but only one lived. Her husband died shortly before the Civil War broke out, leaving her considerable wealth.

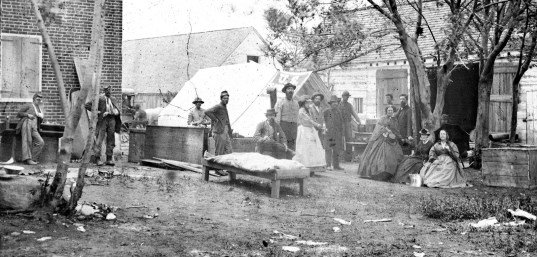

When the Civil War began, Annie was among the first people to organize a Soldier’s Aid Society. She later became their secretary, and devoted herself to relief work. As secretary of the Keokuk Soldiers’ Aid Society, she visited troop encampments and organized a statewide system of local aid societies to collect hospital supplies.

In April 1861, she wrote a letter with a list of items the soldiers needed badly. The response was so great that within ten days she was in the South distributing supplies to Iowa’s soldiers.

Supplies came in a steady stream for sixteen months. The town of Muscatine sent over 1500 bushels of potatoes. A society near Des Moines gave five cows to provide milk for the hospitals. An approximate total of $160,000 worth of supplies passed through her hands during the Civil War.

In 1862, Annie was appointed a Sanitary Agent for the state of Iowa. Her job included the distribution of supplies, correspondence with societies, and securing the necessary papers for soldiers who were going home.

On July 25 1862, Edwin Stanton, Union Secretary of War, issued an order which stated:

Permission is hereby given to Mrs. Annie Wittenmyer, Special Agent of the Iowa Sanitary Association, to pass with such goods as she may have in charge, to add within the lines of any of the Armies of the Departments of Kansas and of the Mississippi, for the purpose of visiting the sick and wounded soldiers of the Iowa Regiments in either of those Armies.

Annie was also concerned with the welfare of soldiers’ orphans. In October 1863, she held a convention of all the Aid Societies in Iowa, where she proposed the idea of an Orphan’s Home. The Orphans’ Home Association was formed. The people rose to the occasion magnificently. The first home was built in Farmington, Iowa.

In 1863, Annie was appointed president of the Iowa State Sanitary Commission. A rival all-male organization, the Iowa Army Sanitary Commission, was trying to take control of its female counterpart. The two groups feuded during Annie’s presidency. Charged with mismanagement of her organization, she successfully refuted the accusations. But the damage was done, and in May of 1864, she left the Commission, but continued her relief work.

With support from the United States Christian Commission, she realized her dream of installing special dietary kitchens in army hospitals. The first was created in Nashville, Tennessee. She trained other women, who installed more kitchens. By the end of the Civil War, the all-male medical department had adopted Annie’s idea.

In 1865, Annie went to Washington to request that the abandoned army barracks at Camp Kinsman at Davenport, Iowa, be donated by the government to serve as a home for orphans of the Civil War soldiers. Secretary of the War Stanton applied to Congress for blankets, sheets, pillows, and other items for the Orphans’ Home.

Rufus Hubbard, the superintendent at Farmington, was sent to Davenport to get the camp ready for the children. On January 22 1866, Congress approved transfer of the camp and all of its equipment to the Iowa Soldiers’ Orphans Association. Hubbard continued as superintendent until April 25, 1866 at which time Annie who had been serving as matron succeeded him.

Annie left Davenport in 1867 to serve as a lecturer, author, temperance worker, and Relief Corps officer. In 1871, she moved to Philadelphia and founded the periodical, Christian Woman, and remained its editor for 11 years.

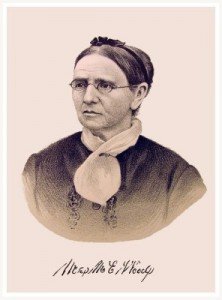

In 1873, Annie threw her support behind the temperance, or anti-alcohol, cause. In November 1874, she attended the Cleveland convention at which the national Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was organized and was elected its first president. For the next year, she and Frances Willard, the WCTU’s corresponding secretary, traveled widely to lecture on temperance and to organize local and state branches.

But politics soon split the WCTU. Annie’s reluctance to incorporate the fight for women’s right to vote into the WCTU caused her to lose her presidency to Frances Willard in 1879. Annie went on to form the Non-Partisan Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, an organization that took temperance as its only cause.

In 1889, she was elected national president of the Women’s Relief Corps of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), where she sought to bring recognition to the efforts of women in the Civil War.

In 1892, she lobbied Congress for the passage of the Army Nurses Pension Law, a bill that would grant pensions to former Civil War nurses. She was rewarded for her efforts when Congress granted her a pension in 1898, at the age of 71.

Annie Wittenmyer died at her home in Sanatoga, Pennsylvania, on February 2, 1900.

My grandfather was Jesse Wittenmyer from Lincoln, Neb. My father was Henry C Wittenmyer and I am Florence R Wittenmyer. Wondering if we may be related to Anni Wittenmyer.

Annie Wittenmyer’s husband did not die before the Civil War. He was divorced from Annie, remarried, and died in Chicago in 1879. The probate of his estate in Centerville, IA leaves part of his property to his and Annie’s son, Charles. Nor was Annie wealthy. Her home barely avoided sheriff’s sale on account of failure to pay taxes. Apparently Mrs. Wittenmyer was more comfortable being a widow than being a divorcee.