Wife of Union General Winfield Scott Hancock

While stationed in southern California just prior to the Civil War, Almira and her husband, future Union General Winfield Scott Hancock, threw a party for the many friends they had made there. Almira Hancock later stated that six of the future Confederates who attended that party were killed by Hancock’s troops at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Childhood and Early Years

Almira (Allie) Russell was the daughter of a prominent merchant in St. Louis, Missouri, where Winfield Scott Hancock was stationed after the Mexican-American War. West Point classmate Don Carlos Buell introduced Hancock to Almira, and after a short courtship, they were married in 1850 and had two children. A career soldier, Major General Hancock was best noted for his leadership at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863.

Winfield Scott Hancock was born on February 14, 1824, in Montgomery Square, Pennsylvania, the son of Benjamin Franklin and Elizabeth Hoxworth Hancock. Descended from a long line of American soldiers, he was christened with the name of America’s greatest living soldier – General Winfield Scott, the hero of the War of 1812.

In 1840, young Hancock received a coveted appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Hancock was then barely sixteen, short and weak; four years later, he was 6′ 2″ and strong. His friends and peers at West Point, who included future Civil War generals: Stonewall Jackson, George B. McClellan, James Longstreet, George Pickett and Ulysses S. Grant. Hancock graduated on June 30, 1844, 18th in a class of 44.

Hancock’s first years in the army were spent along the Red River in Texas, and on the frontier fighting Indians. When war broke out with Mexico in 1846, Hancock requested an assignment in a fighting unit, but he had few achievements to recommend him. Finally, on July 13, 1847, the young officer was transferred to Vera Cruz to serve under his namesake, General Winfield Scott. He was there long enough to get commendations for bravery in four different battles.

Regimental headquarters returned to St. Louis, and West Point classmate Don Carlos Buell introduced Hancock to Almira (Allie) Russell, the daughter of a prominent St. Louis merchant. After a short courtship, they were married on January 24, 1850. The couple had two children, Russell (1850-1884) and Ada Elizabeth (1857-1875).

On November 5, 1855, Lieutenant Hancock was appointed Assistant Quartermaster and ordered to Fort Myers, Florida during the Seminole Wars of 1856-7. Hancock’s young family accompanied him to his new posting, where Allie was the only woman on the post. It was difficult and arduous service, but Hancock was quickly becoming indispensible although, according to Allie, “he very much disliked quartermaster duties.”

Hancock was stationed in southern California in November 1858, and remained there, joined by Allie and the children, serving as a captain under future Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston. There Hancock became friends with several officers from the South. He became especially close to Lewis Armistead of Virginia.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Armistead and the other Southerners were leaving to join the Confederate Army, while Hancock remained in the U.S. Army. On June 15, 1861, Hancock and Allie hosted a party for their friends who were scattering because of the war. Lewis Armistead gave his Bible and personal belongings to Allie for safekeeping – to be opened only if he died in battle.

Hancock headed East to offer his services in the defense of the Union. Arriving in Washington, DC, Hancock was summoned to the Headquarters of General George B. McClellan, who appointed Hancock Brigadier General Of Volunteers in the Army of the Potomac on September 23, 1861.

Hancock’s first action was during the Peninsula Campaign, where he commanded a brigade at the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5, 1862. McClellan telegraphed to Washington that “Hancock was superb today,” and Hancock the Superb was born.

At the Battle of Antietam, Hancock took command of the First Division in the II Corps, after the mortal wounding of Major General Israel B. Richardson in the horrific fighting at Bloody Lane. Hancock made a dramatic entrance onto the battlefield, galloping between his troops and the enemy, parallel to the Sunken Road.

General McClellan was replaced with General Ambrose Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac about that time, and he was replaced by General Joseph Hooker in the spring of 1863. Hancock was promoted to major general on November 29, 1862, and led his division in the disastrous attack on Marye’s Heights in the Battle of Fredericksburg the following month, where he was wounded in the abdomen.

In May 1863, Hancock’s division was instrumental in covering the withdrawal of Federal forces at the Battle of Chancellorsville – another terrible Union defeat – and he was wounded again. When General Darius Couch asked to be transferred out of the Army of the Potomac in protest of the actions of General Hooker, Hancock assumed command of II Corps, which he would lead until shortly before the war’s end.

Hancock at Gettysburg

Hancock would provide his most important service at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. After hearing that General John Reynolds was killed early on July 1, Major General George Gordon Meade, the new commander of the Army of the Potomac, sent Hancock ahead to take command of the units on the field and assess the situation.

At 3:30 PM, on July 1, 1863, Hancock arrived at Gettysburg, and found the commander of the Union XI Corps, Major General Oliver Otis Howard, attempting to establish a defensive position. Federal positions had collapsed both north and west of town, and General Howard had ordered a retreat to the high ground south of town at Cemetery Hill.

Hancock then went to work establishing the Union battle line that would be known as the Fish Hook, and placed Union forces in a strong defensive position on Cemetery Ridge. Hancock’s determination boosted the morale of the retreating Union soldiers, but he played no direct tactical role on the first day.

On the second day, General Robert E. Lee attacked both Yankee flanks simultaneously, when USA General Daniel Sickles attempted to move his III Corps forward into the Peach Orchard. Sickles’ action exposed the Federal left flank just as CSA General James Longstreet launched his attack toward the Round Tops.

Seeing the trouble, Hancock sent his First Division under Brigadier General John Caldwell to aide Sickles. The second brigade of that division was the famed Irish Brigade. Prior to marching to the relief of Sickles, Father William Corby, the chaplain of the Irish Brigade, gave the soldiers general absolution for their sins.

In the evening, the Confederates reached the crest of Cemetery Ridge, but could not hold the position in the face of counterattacks from the II Corps, including an almost suicidal counterattack by the First Minnesota against a Confederate brigade, ordered in desperation by Hancock.

On the third day at Gettysburg, General Meade placed Hancock in command of the I and III Corps, along with his own II Corps. Hancock was then commanding three-fifths of the Army of the Potomac.

General Lee planned to have Longstreet command General George Pickett’s Virginia division plus six brigades from General A. P. Hill‘s Corps in an infantry attack on General Hancock’s II Corps position at the right center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. Prior to the attack, Confederate artillery would try to weaken the Union line.

Around 1 PM, between 150 to 170 Confederate guns began an artillery bombardment that was probably the largest of the war. After waiting about 15 minutes, 80 Federal cannons added to the din. During the artillery attack, Hancock rode along his line encouraging his men to hold their ground. A soldier who witnessed Hancock that day stated, “His daring heroism and splendid presence gave the men new courage.”

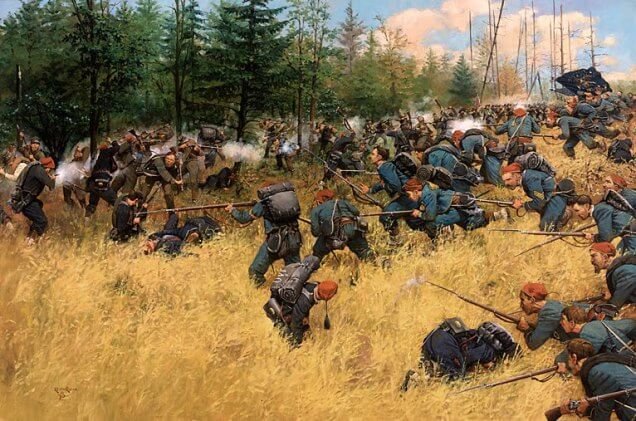

At about 3 PM, the cannon fire subsided, and 12,500 Southern soldiers from the command of General George Pickett stepped from the ridgeline and began to cross three-quarters of a mile of open ground, under intense fire from Union artillery massed on Cemetery Ridge, in what would be forever known as Pickett’s Charge.

In addition to the musketry and canister fire from Hancock’s II Corps, the Confederates suffered fierce flanking artillery fire from Union positions north of Little Round Top. Although the Federal line wavered and broke temporarily at a jog called the Angle, at a low stone fence just north of a patch of vegetation called the Copse of Trees, reinforcements rushed into the breach, and the Confederate attack was repulsed.

Hancock was not idle during the attack; he seemed to be everywhere on the battlefield, directing regiments and brigades into the fight. As he approached the Vermont Brigade commanded by Brigadier General George Stannard, Hancock suddenly reeled in his saddle and began to fall to the ground. Two of Stannard’s officers sprang forward and caught Hancock as he fell.

A bullet had struck the pommel of Hancock’s saddle and penetrated eight inches into his right groin, carrying with it some wood fragments and a large bent nail from the saddle. His aides applied a tourniquet to stanch the bleeding; Hancock removed the nail himself, and is said to have remarked wryly, “They must be hard up for ammunition when they throw such shot as that.”

During the infantry assault, General Hancock’s old friend, CSA General Lewis Armistead and his men reached the stone wall near the Copse of Trees. Armistead’s brigade got farther in the charge than any other, but they were quickly overwhelmed. This event has been called the High Watermark of the Confederacy – the closest they ever came to winning Southern independence.

Armistead was shot three times just after crossing the stone wall. Captain Henry Bingham of Hancock’s staff rushed to Armistead and told him that his old friend Hancock had just been wounded a few yards away. This scene is featured in Michael Shaara’s novel, The Killer Angels, in which Armistead is a principal character. Armistead was taken to a Union field hospital at the George Spangler Farm, where he died two days later.

General Hancock refused to leave the field until his troops had repulsed the Confederate attack. Though in much pain, he continued to direct and encourage his men. The Union victory was largely the result of the leadership of Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, and Gettysburg marked the zenith of his military career.

Hancock was taken to his father’s home in Norristown, Pennsylvania to recover. He was received at Norristown by his fellow citizens, and borne to his home on a stretcher, on the shoulders of soldiers of the Invalid Corps. When Hancock had recovered enough to travel to West Point, he was honored with public receptions there, in New York, and at St. Louis, where he went to see his family.

Image: General Winfield Scott Hancock

The Overland Campaign

In March, 1864, Hancock was again ordered to the front, and he led his old corps through General Ulysses S. Grant’s spring 1864 Overland Campaign, from the Rapidan to Petersburg. Grant was committed to a war of attrition, in which the superior Union forces would bleed Lee’s army dry. Union casualties would be high, but the Union had greater resources to replace lost soldiers and equipment.

Hancock served with distinction in the strenuous and bloody series of battles that began in the Wilderness in early May, and continued through Yellow Tavern, North Anna, Old Church, Cold Harbor, Trevilian Station, and finally to the ten-month siege at Petersburg, Virginia.

At Spotsylvania Court House on May 12, 1864, Hancock led a magnificent pre-dawn charge at the head of his whole corps of 20,000 men. The target was the Mule Shoe – a salient in the Confederate trenches. In less than an hour, the II Corps broke through the Rebel lines. Hancock took close to 4,000 prisoners, destroying a whole division of the Confederate Second Corps.

Hancock sent a brief despatch to General Grant: “General, I have captured from thirty to forty guns. I have finished up Johnson, and am now going into Early,” (Confederate Generals Edward “Allegheny” Johnson and Jubal Early). For those heroic efforts, Hancock earned the rank of major general. In June, his Gettysburg wound reopened, but he soon resumed command, sometimes traveling by ambulance.

Second Battle of Reams Station

Hancock’s only significant defeat occurred during the Siege of Petersburg. Soon after the Union success at the Battle of Weldon Railroad, Hancock’s II Corps was ordered to move south along that rail line, destroying track as it went. By late August 24, 1864, the II Corps was three miles south of Reams Station, when Hancock was informed that CSA General A.P. Hill’s infantry and General Wade Hampton’s cavalry were moving out of Petersburg’s defenses to meet this threat.

During the morning of August 25, Hampton started driving Hancock’s troops back up the Halifax Road toward Reams Station. Hill determined that a large frontal assault was needed to drive the Union forces off the railroad. It was 5:00 pm before the Confederates were ready for their second assault, and it began with a heavy artillery barrage.

Hampton and Hill were finally able to coordinate an attack upon the Union position, and under this pressure, overran the Union position, capturing 9 guns, 12 colors, and many prisoners. The II Corps was shattered, and swept from the field by 7:00 pm. Hancock realized his greatest defeat as a corps commander, losing nearly 3000 soldiers as casualties or as prisoners.

In Grant’s campaign against Lee, Hancock and his famed II Corps had been repeatedly called upon to plunge into the very worst of the fighting, and the casualties had been terrible. At the beginning of May 1864, the II Corps numbered 30,000 officers and men. Casualties since then had topped 26,000 killed, wounded or missing and he felt their losses deeply.

General Winfield Scott Hancock asked to be relieved of command of the II Corps on November 25, 1864. Constant pain from his old wound – he had never regained full mobility nor his youthful energy – and the loss of so many of his men contributed to his decision to give up field duty.

Hancock’s farewell message November 26, 1864:

Conscious that whatever military honor has fallen to me during my association with the Second Corps has been won by the gallantry of the officers and soldiers I have commanded… in parting from them, I am severing the strongest ties of my military life.

Hancock’s first assignment after leaving field duty was to command the ceremonial First Veterans Corps, a largely ceremonial post. For the next three months, Hancock was at Washington organizing wounded veterans for service – as much as his health would permit. He did more recruiting, commanded the Middle Department, and relieved General Philip Sheridan in command of forces in the now-quiet Shenandoah Valley.

By spring 1865, the war had ended at Appomattox Court House, and General Hancock – who for three years had been one of the most conspicuous figures in the Army of the Potomac – was not there to take part in the final triumph.

Execution of Lincoln Assassination Conspirators

In April 1865, General Hancock was summoned to Washington to take charge of carrying out the execution of the Lincoln Conspirators. President Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated on April 14, 1865, and by May 9, a military commission had been convened to try the accused. The assassin John Wilkes Booth was already dead, but his co-conspirators were quickly tried and convicted. President Andrew Johnson ordered the executions to be carried out on July 7.

Although Hancock was reluctant to execute some of the less-culpable conspirators, especially Mary Surratt. He wrote to Judge Clampitt, Surratt’s legal counsel:

I have been on many a battle and have seen death, and mixed with it in disaster and in victory. I have been in a living hell of fire, and shell and grapeshot, and, by God, I’d sooner be there ten thousand times over than to give the order this day for the execution of that poor woman. But I am a soldier, sworn to obey, and obey I must.

Hancock hoped that Surratt would receive a pardon from President Johnson, so hopeful that as commander of the Middle Military District, he posted messengers all the way from the Arsenal to the White House, ready to relay the news to him at a moment’s notice, should the pardon be granted. It was not.

Hancock remained in the postwar army as brigadier general. In 1866, Ulysses S. Grant had him promoted to major general in the regular army, and he served at that rank for the rest of his life. He was sent west to command the Military Department of Missouri based at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, but his time there was brief.

On November 29, 1868, President Andrew Johnson named Hancock to replace Philip Sheridan as military governor of Louisiana during Reconstruction. It was in this position, that he would issue General Order Number 40, that would essentially allow the civilian government to quickly replace the military government. Hancock’s refusal to use military authority to assist Republican radicals strengthened his ties to Democrats and angered Grant.

With the death of General George Gordon Meade in 1872, Hancock became the senior major general in the U.S. Army, and was assigned to take Meade’s place as commander of the Division of the Atlantic at Governor’s Island in New York harbor. Enjoying the fine living there, Hancock eventually weighed over 250 pounds.

Winfield and Allie were devastated by the early deaths of both of their children within a ten-year span. Their 18-year-old daughter Ada died of typhoid fever in 1875 in New York City. Son Russell, who was always sickly, left a wife and three children when he died on December 30, 1884, in Mississippi.

Presidential Candidate

Democratic strategists had considered Hancock a potential presidential nominee as early as 1864, and his name resurfaced during subsequent presidential campaigns. He finally received the Democratic nomination for President in 1880. He and Allie found the constant flow of political visitors maddening.

The Republicans nominated James A. Garfield, a longtime Ohio congressman, and attacked Hancock’s complete lack of political experience. Neither candidate for the 1880 Presidential Election inspired voters to shift political allegiance. Garfield won by less than ten thousand votes. But Hancock was the first Northerner to carry the Southern states since the war.

Hancock had refused to be examined by a doctor, despite the illnesses that plagued him late in life, maybe because the field surgeons at Gettysburg had caused horrible suffering in trying to remove the bullet and bone fragments from his wound. He had been ill for several days when doctors discovered that he had severe diabetes. He became delirious on the evening of February 5.

Winfield Scott Hancock died on February 9, 1886, at 2:35 PM, five days before his sixty-second birthday, at Governor’s Island, still in command of the Military Division of the Atlantic. After a brief funeral service at Trinity Church in New York City February 12, 1886, General Hancock’s remains were taken to his boyhood home of Norristown, PA, and placed alongside his daughter Ada in a mausoleum that he had designed.

Almira Russell Hancock received many requests to write about her husband and his military experiences and his correspondence. Her memoir, Reminiscences of Winfield Scott Hancock, was published in 1887 by Mark Twain’s publishing firm, Webster & Company. Afterward, she burned Hancock’s letters.

Almira Russell Hancock died in April 1893 and was buried near her family in St. Louis, Missouri. Although she outlived both of her children, she was survived by the three grandchildren fathered by her son Russell.

New York Times Article, April 23, 1893:

The funeral of Mrs. Almira Russell Hancock, widow of General Winfield Scott Hancock, who died at her home, the Gramercy, 34 Gramercy Park Thursday afternoon, took place yesterday at noon at the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Transfiguration on East Twenty-ninth Street.

Bronze by Frank Edwin Ewell

Gettysburg National Military Park

Photograph of monument taken after an ice storm

Winfield Scott Hancock was a very able military commander. To the North, he was known as Hancock The Superb. The South called him The Thunderbolt of the Army of the Potomac. The Sioux and the Cheyenne called him Old Man of the Thunder. A man of great charisma and a commanding physical presence, he was a soldier’s soldier, something of an artist, amateur scientist, botanist, and he even wrote some verse.

SOURCES:

Battle of Gettysburg

Winfield Scott Hancock

Battle of Boydton Plank Road

Wikipedia: Winfield Scott Hancock

Major General Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock, Major General, USA

Winfield Scott Hancock – U.S. Major General

Gettysburg Daily Photos