Black Women Intelligence Agents in the Civil War

Other than a very few famous African American women spies, little is known about the black women who gathered intelligence for the Union during the Civil War. We do know that some were former slaves and others were free women who volunteered to spy on the Confederacy, often at great risk to their own personal safety.

Other than a very few famous African American women spies, little is known about the black women who gathered intelligence for the Union during the Civil War. We do know that some were former slaves and others were free women who volunteered to spy on the Confederacy, often at great risk to their own personal safety.

Image: Unidentified African American Woman

Escaped slaves served as a primary source of intelligence for the Union Army. Throughout the official records of the war, however, there are frequent references to bits of intelligence coming from contrabands, a term that dates back to early 1861 at Fort Monroe, Virginia. General Benjamin Butler refused to return three escaped slaves to slaveholders who supported the Confederacy, referring to the slaves as contraband of war. The term caught on.

Runaway slaves gave the Union Army a continually flowing stream of intelligence. So did slaves who volunteered to be in-place agents. Other African Americans risked their lives in secret, intelligence-gathering missions or while entering enemy territory as scouts. There are few direct references to the contributions of specific women in historical records, mainly because documents were destroyed to protect their identities.

Southern black women operating as spies, scouts, couriers and guides were willing and able to gather extensive information about Confederate operations. Black Dispatches resulted from frontline debriefings of slaves – either runaways or those having just come under Union control. Black Americans also contributed to tactical and strategic Union intelligence through behind-the-lines missions.

Black Dispatches

The value of the information that could be obtained by black Americans behind Confederate lines was clearly understood by most Union generals early in the war. A stream of articles and stories in the Northern press during the war also made the public aware. All intelligence was helpful, but in-place agents could provide the enemy’s future plans. Intelligence provided by slaves and free African Americans were called black dispatches.

The Dabneys

Black Americans made significant contributions to Union intelligence during the War. Because of the culture of slavery in the South, blacks performing menial activities could move about without suspicion. A black couple provided intelligence about Confederate troop movements to the Union during the fighting around Fredericksburg, Virginia in 1863.

A runaway slave named Dabney crossed into the Union lines with his wife and found employment in General Joseph Hooker‘s headquarters camp. A few weeks later, Dabney’s wife returned to Confederate territory after learning that her master, a Southern woman, was returning to her home nearby. Shortly thereafter, Dabney began reporting Confederate movements to Hooker’s staff. Union officials soon discovered that his reports were accurate, and asked him where he got his information.

Dabney led them to an elevated area in the camp, from which they had a clear view of Fredericksburg and much of the surrounding area. He pointed to a house on the outskirts of the town, along the river bank. In its yard was a clothesline where clothing, sheets and towels were hung out to dry.

Dabney explained that he and his wife had worked out their own signaling system using the laundry that she hung out to dry for her employer. Whenever she saw troops moving through the area or overheard Confederate soldiers discussing their future plans, she would rush to the clothesline and hang items in particular formations, sending Dabney a coded message.

For example, a white shirt stood for General A. P. Hill, pants hung on the clothesline upside down indicated the direction west, etc. While this system could send simple messages such as “Hill-north-three regiments,” its use was extremely limited. However, that does not diminish the courage and commitment these individuals demonstrated by their actions. It illustrates the extent to which African Americans would go to assist their saviors, the Union Army.

Mary Touvestre

Valuable intelligence was also provided to the Union Navy by African Americans. Shortly after the war began in early 1861, fearing that the Confederacy would take control of the Gosport Shipyard in Portsmouth, Virginia – a U.S. Navy facility for building and repairing ships – the Navy commander ordered that the shipyard be burned on April 21, 1861. Union forces withdrew to Fort Monroe, the only land in the area still in Union control.

The Confederate forces did capture the shipyard soon after through an elaborate ruse set up by civilian railroad builder (later a Confederate general) William Mahone. The capture of the shipyard allowed a tremendous amount of war material to fall into Confederate hands – 1,195 heavy guns alone were captured and used to defend the Confederacy.

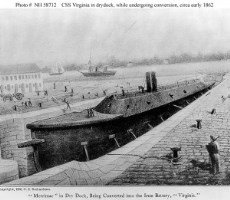

In the haste to abandon the shipyard, the U.S. Navy ship Merrimack had only been destroyed above the waterline when Federal forces abandoned the shipyard. In early 1862, the Confederates began rebuilding the hulk of the Merrimack, a steam-powered frigate, as an ironclad, renaming her the CSS Virginia.

Image: Confederate Ironclad, the CSS Virginia

Image: Confederate Ironclad, the CSS Virginia

In late 1861-early 1862, Mary Touvestre, a freed slave, was working as a housekeeper for one of the engineers who were rebuilding the Merrimack into the CSS Virginia, the first Confederate ironclad warship. Touvestre overheard her employer talking about the new ship.

Realizing the threat the CSS Virginia posed to the northern blockade, Touvestre stole a set of plans for the ship and fled North. Traveling from Portsmouth to Washington, DC, Touvestre risked severe punishment if Confederate authorities captured her with the plans. After a dangerous trip, she arrived in the capital and arranged a meeting with Naval officials, who passed the information on to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles.

Touvestre’s warning convinced officials of the need to speed up construction of the Union’s own ironclad, the USS Monitor. The Virginia was still able to destroy two Union frigates, the USS Congress and the USS Cumberland, before the Monitor was completed, but it could have been worse. Some historians believe that if Touvestre had not warned the Navy, the Virginia might have thwarted the blockade long enough for the Confederacy to receive desperately needed supplies from Europe.

The ironclad CSS Virginia waged war on the Union fleet all day on March 8. This engagement was part of a Confederate effort to break the Union blockade of Southern ports. Unfortunately, the USS Monitor did not arrive in Hampton Roads until later that night, too late to save many of the Union ships from partial or total destruction.

On March 9, at the Battle of Hampton Roads, often referred to as the Battle of the Ironclads, the CSS Virginia sailed out to finish off the remaining fleet when she was met by the USS Monitor. The ships battled for about four hours to a draw. Its major significance was that it was the first meeting of ironclad warships. The Confederates burned the Gosport Shipyard again when they retreated in May 1862.

Mary Elizabeth Bowser

The Richmond Underground was a Union spy ring run by Elizabeth Van Lew, whose wealthy family was well respected in Richmond. Van Lew did not hide her Union sympathies, but because of her eccentric behavior she appeared harmless to Confederate officials. Before developing her own cipher, she tore important messages into pieces and transported them by multiple couriers in the soles of shoes and the shells of eggs.

Van Lew soon realized the espionage value of a slave who was secretly able to read and write. Her former slave Mary Elizabeth Bowser was well educated by Van Lew, but she pretended to be an illiterate slave, and Van Lew made sure she was hired as a regular employee at the Confederate White House after working several social functions there.

Because the Southern leaders and military officers considered slaves illiterate and incapable of independent thought, they misjudged the intelligence and cleverness of African Americans. Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his guests openly discussed Confederate military plans and government issues, and Davis left important documents on the desk in his study.

Image: Confederate White House

Image: Confederate White House

Davis never dreamed that Bowser was one of the Union’s first and most effective agents who had infiltrated the inner sanctum of the enemy and extracted some of the most guarded secrets of the Confederacy. Each night after she finished her duties, Mary would meet Van Lew at isolated locations on the outskirts of Richmond to exchange information. Upon her arrival, Bowser recited from memory the private conversations and documents she had witnessed that day.

In the fall of 1865, Mary Elizabeth Bowser gave an address in Brooklyn alluding to her infiltration of the Confederate White House during the war. Though her story has been difficult to document, Bowser’s willingness to risk her life as part of the Richmond underground is certain.

General Tubman

One of our nation’s most famous African Americans, Harriet Tubman was also one of the war’s most daring and effective spies. Unlike many others, her espionage activities are well documented. Early in 1863, Union officers on the coast of South Carolina decided that Tubman would be invaluable to them as a covert operative.

Tubman was asked to assemble a small reconnaissance unit of ex-slaves who knew the area well; she recruited nine men, some of them riverboat pilots who intimately knew the waterways throughout the coastal lowlands. One of her most important missions was to identify the location of the remotely-detonated mines the Confederates had placed along the waterways that were patrolled by Union boats.

In July 1863, Colonel James Montgomery asked Tubman to lead a night raid up the Combahee River, near Beaufort, South Carolina. Union gunboats, carrying some 300 black soldiers, slipped up the river, eluding the mines that Tubman and her crew located. Undetected, they swept ashore, destroyed a Confederate supply depot, burned homes and warehouses, and liberated more than 750 slaves from nearby rice plantations.

The story of General Tubman’s Combahee Raid appeared on the front page of The Commonwealth, a Boston newspaper, on Friday, July 10, 1863. This an excerpt:

The Combahee strategy was formulated by Harriet Tubman as an outcome of her penetrations of the enemy lines and her belief that the Combahee River countryside was ripe for a successful invasion. She was asked by General Hunter “if she would go with several gunboats up the Combahee River, the object of the expedition being to take up the torpedoes [mines] placed by the rebels in the river, to destroy railroads and bridges, and to cut off supplies from the rebel troops.

She said she would go if Col. Montgomery was to be appointed commander of the expedition… Accordingly, Col. Montgomery was appointed to the command, and Harriet, with several men under her, the principal of whom was J. Plowden… accompanied the expedition. Actually in this raid it was Montgomery who was the auxiliary leader. The whole venture owed its success to the complete preliminary survey made by Harriet Tubman’s espionage troops.

Captain John F. Lay, the Confederate investigating officer, discussing the movement afterwards, stated, “The enemy seems to have been well posted as to the character and capacity of our troops and their small chance of encountering opposition, and to have been well guided by persons thoroughly acquainted with the river and country.” It was a commentary, however indirect, on Harriet’s work and the labor of her subordinates.

After the War

The intelligence contributions of black Americans became obscure after the war ended. Racial prejudice probably played a part in this, as it did in subduing information about the contributions of African American Union military regiments. However, most spies did not want their identities made public, and many records were purposely destroyed in the emotional period following the Civil War, when many of these African American women continued to live near people still loyal to the South.

In Washington, DC, the War Department turned over portions of its intelligence files to many of the participants involved, and most of those records were destroyed or lost. Therefore, accounts by individuals of their parts in the war or official papers focusing on those subjects have become important sources of information, much of which is difficult to substantiate due to the lack of supporting documents.

On the Confederate side, one of the last act of Confederate Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge before fleeing Richmond in April 1865 was to destroy virtually all intelligence files, including counterintelligence records regarding Union spies. With the surrender of the Confederacy, Breckinridge fled the country, abdicating his post.

Twenty-four books were published after the war by self-proclaimed spies or counterspies – nineteen by men and five by women. Seventeen of these books were written by so-called Union spies and seven by Confederates. None were written by African Americans. For too long, black women have been rendered invisible in Civil War history. It is time to give them their due.

SOURCES

CIA.org: Black Dispatches

Wikipedia: Black Dispatches

Wikipedia: Norfolk Naval Shipyard

CIA.org: Intelligence in the Civil War