Civil War Nurse in St. Louis, Missouri

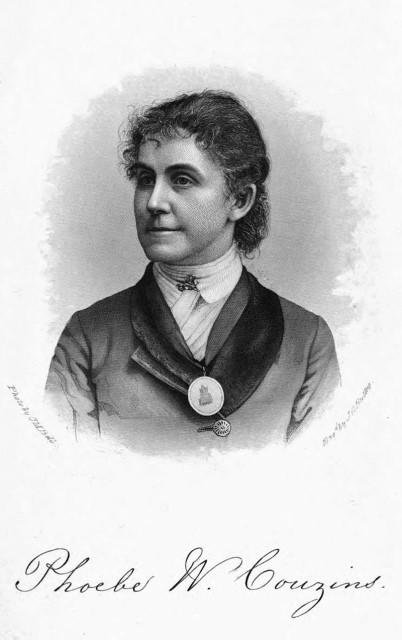

Union Nurse: Adaline Weston Couzins

Adaline Weston Couzins was a Union nurse in Missouri. She was one of the Civil War Nurses on Hospital Ships that traveled up and down the Mississippi River, risking her life helping wounded soldiers. A Minie ball struck her in the knee in 1863, but she kept on nursing throughout the war and afterward. She was a woman of great courage and compassion for her fellow men and women.

Early Life

Adaline Weston was born August 12, 1815, in Brighton, England. At the age of eight, she came to America with her parents. In 1834, Adaline eloped with John Edward Decker Couzins, a carpenter and builder by trade. Her husband held the position of chief of police in St. Louis throughout the Civil War and a U.S. marshal for the eastern district of Missouri from 1884 to 1887. Adaline gave birth to four children, and their daughter Phoebe Wilson Couzins was one of the first women in the United States to earn a law degree.

Adaline Weston Couzins began her nursing career as a volunteer relief worker during a cholera epidemic that hit St. Louis, Missouri in 1849, only the first time she worked as a tireless public servant. Cholera is a severe bacterial infectious disease caused by bacteria. The classic symptoms are diarrhea and vomiting that can quickly lead to dehydration. Symptoms start two hours to five days after exposure. There were very few hospitals in the United States at that time and even fewer nurses. Family members or servants had to nurse the sick back to health.

Civil War

After the Civil War had begun in April 1861, Couzins volunteered her services to one of the city’s leading surgeons, Dr. Charles Pope. She and her husband met the first train transporting wounded soldiers to St. Louis from the Battle of Wilson’s Creek on August 10. They helped Union medical personnel carry the men into a hospital, where Adaline “washed and dressed them with the appliances of hospital stores she had gathered together when news came of the battle.”

Jessie Benton Fremont, a native of St. Louis and wife of General John C. Fremont, noticed the casualty crisis in St. Louis and convinced her husband to approve the plan for the Western Sanitary Commission (WSC) and it was established September 10, 1861. The Commission assisted the Medical Department of the Army by providing doctors and nurses and building military hospitals. The first such facility held 500 patients, but they needed many more beds.

Ladies Union Aid Society

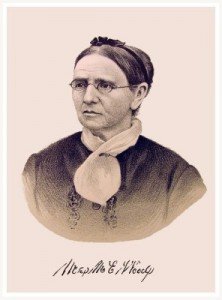

Other relief organizations like the Ladies Union Aid Society (LUAS), organized on August 2, 1861, were soon formed in several other cities. Adaline Weston Couzins joined the Ladies Union Aid Society of St. Louis, an all-female organization that provided funds, supplies, and volunteers. LUAS members provided a wealth of handmade items and cash to be distributed by the WSC. The Society also brought women into the public sphere as they raised money and collected supplies. Perhaps their most important role was nursing sick and wounded soldiers.

The Union Army was ill-prepared to care for the massive number of casualties sustained during the first few battles. Therefore, the aid provided by organizations like the WSC and LUAS was invaluable. The women collected supplies – what the nurses called comforts – such as blankets, pillows, and sheets; underwear, socks, slippers, towels and handkerchiefs. Foods and spirits were also popular, like dried and canned fruits, jellies, butter, and crackers; packages of farina and bushels of vegetables; and bottles of wine, brandy and whiskey. These articles were almost always free gifts from loyal Union women.

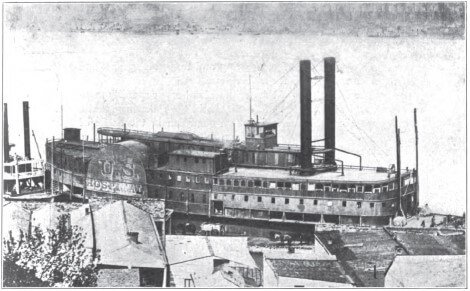

Image: Red Rover Hospital Ship at Vicksburg, Mississippi

Image: Red Rover Hospital Ship at Vicksburg, Mississippi

The WSC and the LUAS also assisted in the creation of hospital ships on the Mississippi River. One of those ships, the City of Louisiana, transported the wounded from Pittsburg Land, Tennessee after the Battle of Shiloh to military hospitals in St. Louis. Couzins worked tirelessly washing and bandaging wounds and comforting injured soldiers. While working on the ships, the women wore long black dresses with large white aprons.

LUAS members also traveled to the battlefields where they dealt firsthand with wounded soldiers, where conditions were difficult and sometimes dangerous. Adaline Couzins and another society member, Arethusa Forbes, volunteered to inspect and report the number of casualties left in the wake of General John C. Fremont’s march through Missouri in the winter of 1862. The women worked quickly in sub-zero temperatures. When they returned to St. Louis, a long line of hospital train cars was sent to retrieve the wounded, men who would have likely died if not for the actions of these brave women. Both women suffered from severe frostbite; Forbes never fully recovered.

Couzins was undaunted by the experience. She volunteered to go with Dr. Simon Pollack, chief surgeon for the Western Sanitary Commission, to Tennessee, to bring back the wounded from the Battle of Fort Henry, fought on February 6, 1862. They were the first in the Civil War to use river steamers as hospital ships to carry the wounded from the battlefield to military hospitals in the North.

Carrying supplies provided by the LUAS, Couzins attended to the wounded after several major battles in the Western Theater, including Shiloh; Donaldson; Corinth; Fort Pillow; Vicksburg. Some women were unsuited to work on the battlefields or steamers duty, but Couzins was considered by those around her to be perfect for the job. The Society also brought women into the public sphere as they raised money and collected supplies.

Unlike women of the U.S. Sanitary Commission and most Union Army nurses, Couzins received no compensation for her many hours of grueling work. She paid for her transportation to the battlefields and sometimes for others as well.

Injured in Battle

Despite the grueling work, emotional strain, and physical danger, Adaline Couzins continued to work on the hospital boats. In the summer of 1863, during General Ulysses S. Grant’s siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi, a Minie ball fragment struck Couzins in the knee. While not serious enough to stop her work, the wound gave her problems in later years. She continued volunteer nursing until the end of the war.

Minie Balls

French army officer Claude-Etienne Minie invented the bullet that bore his name in 1849. The Minie ball was a cylindrical bullet with a cone on top and a hollow base made out of iron that expanded when fired. It was accurate over long distances and was soon used by the British army in the Crimean War. Both Union and Confederate soldiers used the Minie ball in their muzzle-loading rifles. When they rammed the ball into the charge, the heat caused the bullet to expand in the grooves of the spiraled rifle causing it to spin at incredible speeds.

Minie Ball Wounds

The Minie Ball was also infamous for the incredible damage it inflicted on human flesh. Upon entering the body, the ball shattered, completely destroying bones and everything else in its vicinity. Because bone could not heal itself after sustaining such an injury, the limb affected was almost always amputated. If the patient did not die during the amputation, he would almost certainly fall victim to infection, which was rampant in unsanitary Civil War field hospitals. This excerpt from A System of Surgery (1873) by William Todd Helmuth, M.D. explains the types of wounds caused by the Minie ball during the Civil War:

The effects are truly terrible; bones are ground almost to powder, muscles, ligaments, and tendons torn away, and the parts otherwise so mutilated, that loss of life, certainly of limb, is almost an inevitable consequence. None but those who have had occasion to witness the effects produced upon the body by these missiles, projected from the appropriate gun, can have any idea of the horrible laceration that ensues. The wound is often from four to eight times as large as the diameter of the base of the ball, and the laceration so terrible that mortification almost inevitably results.

Grand Mississippi Valley Sanitary Fair

In January 1864, the Western Sanitary Commission began organizing the Grand Mississippi Valley Sanitary Fair. The fair’s purpose was to raise money for the war effort. It opened on May 17, 1864 and ran until June 18. General William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Department of the West, was named honorary president of a male executive committee. However, the real work was done by a separate executive committee of women. After paying for admission, visitors walked past rows of booths selling all sorts of goods. The money from the fair went to help the WSC and the LUSA.

By 1864 the WSC had funded more than 70 hospitals around the southwest and ran 15 in Saint Louis. It provided aid throughout the war including at the major battles of Shiloh, Pea Ridge, and Vicksburg. Members did more than provide medical aid, though. They provided homes for soldiers who had been discharged or were on leave and could not afford hotels or lodging. They also provided aid to freedmen, white refugees from the South, and Union prisoners of war such as those at Andersonville.

Throughout the remainder of the Civil War, Adaline Couzins traveled up and down the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers on the steamers that had been transformed into floating hospitals. Doctors who served beside Couzins intelligent, experienced, capable, and very reliable.

Women’s Rights

Women who served in leadership roles in organizations like The Ladies Union Aid Society learned a great deal about business and public life. These experiences expanded their role in society and had a lasting impact on women’s rights after the war. Opportunities opened up for women in fields such as nursing. Understandably, many of the women leaders during the Civil War served as activists in the women’s suffrage movement and forged successful careers.

Adaline Couzins headed the Ladies Sanitary Corps of the Special Health Department of St. Louis and was one of the founders of the Female Guardian Home of St. Louis. She also applied to Edward Bates, President Abraham Lincoln‘s attorney general, for the position of head of the St. Louis post office. As he read her petition, Bates thought to himself that “no one in our country deserves it more, and I know you will do the office justice.” She did not get the job, but Bates’ confidence in her gave her the inspiration to continue.

Image: Minie Ball Fragment

Image: Minie Ball Fragment

Similar to the one that struck Couzins in the knee at Vicksburg

Late Years

Adaline’s battle wound grew painful as she aged and hindered her ability to walk, but she remained as committed as ever to her work as a public servant. However, she became increasingly immobile and finally bedridden in old age.

Phoebe Couzins solicited the United States Government to come to her mother’s aid. Many who were aware of Adaline’s great work during and after the Civil War wrote letters telling of her invaluable service. Many St. Louisans prepared testimonials, citing her unrelenting efforts as a nurse in that city before, during and after the war. Excerpt from Portraits of Conflict: A Photographic History of Missouri in the Civil War (2009):

Couzins returned to volunteer nursing during an 1866 outbreak of cholera. In the postwar years she and her two daughters were active in the women’s suffrage movement. By 1888 she was bedridden thanks to her war wound. Arethusa Forbes successfully petitioned Congress for a disability pension for her friend, testifying, “That petticoat with the rebel bullet-hole and the bent hoop skirt … ought to speak loudly for a pension.”

On May 27, 1888, Congress passed Bill 2356 granting Adaline Couzins a government pension.

Adaline Weston Couzins died in St. Louis May 9, 1892 at the age of seventy-seven, a respected community leader whose many contributions were widely acknowledged. She is buried at Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

Arethusa Forbes wrote a letter to Phoebe Couzins years later in which she recalled an incident when Adaline briefly took charge of patient care on one of the hospital ships. The “regular male doctors lay drunk in their cabins on liquors furnished by the Ladies Union Aid for the wounded soldiers.”

SOURCES

Ladies’ Union Aid Society

In Her Place: A Guide to St. Louis Women’s History

Western Sanitary Commission and Ladies Union Aid Society