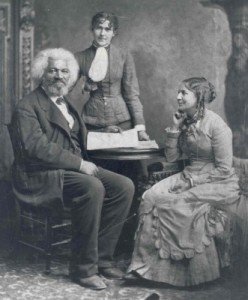

Educator, Feminist and Wife of Frederick Douglass

Standing is Helen’s sister Eva Pitts

Helen Pitts Douglass (1838–1903) was a teacher and feminist, and the second wife of former slave, abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Frederick Douglass. She created the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association, and spent the last years of her life trying to build a memorial to her deceased husband, who is recognized as the father of the civil rights movement.

Helen Pitts was born in 1838 in Honeoye, New York. She attended school at the Genesee Wesleyan Seminary in Lima, New York, and graduated from Mary Lyon‘s Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College) in 1859.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) was a famous abolitionist, writer, lecturer and statesman. He was born a slave on Maryland’s Eastern Shore and was given the name Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. At an early age, he learned to read and write, and escaped to freedom in the North, changing his name to Douglass to avoid recapture.

Eventually he settled in Rochester, New York, and was active in the abolitionist movement. He was a leader of Rochester’s Underground Railroad and became the editor and publisher of the North Star, an abolitionist newspaper. Throughout his life, Douglass remained an outspoken advocate for the rights of African Americans.

Douglass also advocated the rights of women and participated in the first Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls in 1848 and signed the Declaration of Sentiments. After the convention, Douglass published a positive editorial on “The Rights of Women,” which appeared in the July 28, 1848 edition of the North Star.

The History of Woman Suffrage notes that during the subsequent adjourned Women’s Rights Convention held in Rochester on August 2, 1848, “Frederick Douglass… advocated the emancipation of women from all the artificial disabilities, imposed by false customs, creeds and codes.” In 1853, Douglass signed “The Just and Equal Rights of Women,” for the Woman’s Rights State Convention held in Rochester, and spoke at that meeting.

During the Civil War, Douglass asked President Abraham Lincoln to make abolition a goal and fought for the right of African Americans to enlist in the Union Army. Douglass then helped to recruit African-American soldiers and wrote a popular editorial entitled “Men of Color, To Arms,” which became a recruiting poster.

After the Civil War, Frederick Douglass moved to Washington, DC. During his tenure there, Douglass held a number of government posts. From 1877 to 1881, he served as US Marshall for the District of Columbia under the administration of President Rutherford B. Hayes. He was appointed the District of Columbia’s Recorder of Deeds by President James A. Garfield, and served in that post from 1881 to 1886. He was the U.S. Minister to Haiti under President Benjamin Harrison, and served in this post from 1889 to 1891.

Women in Education

After the war, Helen Pitts taught at the Hampton Institute in Virginia, which was founded by black and white leaders of the American Missionary Association after the Civil War to provide education for freedmen. After several years there, tensions mounted when Helen caused the arrest of local residents whom she thought had insulted and abused her students. Poor health forced her to return to Honeoye.

In 1882 Pitts moved to Washington, DC to live with her uncle. Pitts continued her interest in the women’s rights movement and co-edited a radical feminist publication called The Alpha with Dr. Caroline Winslow, president of the Moral Education Society of Washington. Pitts wrote articles and assisted in the publication of the newspaper.

That same year Frederick Douglass hired Helen Pitts as a clerk after he was appointed the Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia. Because he was writing his autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass and was often lecturing, Pitts helped him frequently in his work. Douglass’ first wife, Anna Murray Douglass, died on August 4, 1882 after a long illness.

On January 24, 1884 Helen Pitts married Douglass; he was 66 and she was 46. The ceremony was performed by Reverend Francis Grimke, mixed race nephew of Sarah and Angelina Grimke. “Love came to me, and I was not afraid to marry the man I loved because of his color,” Helen said. They lived together at Douglass’ home Cedar Hill, named after the cedar trees that shaded the house. Douglass had moved to Cedar Hill, when he became US Marshal of the District of Columbia in 1877.

Frederick and Helen Pitts Douglass faced a storm of controversy as a result of their marriage. Interracial marriages were still a rarity, and illegal in some states. Although Helen’s father Gideon Pitts was an abolitionist friend to Douglass and the Pitts home was a stop on the Underground Railroad, her family were against the marriage and stopped talking to her. Douglass’ children felt his marriage was a repudiation of their African American mother.

Because Helen was a direct descendant of Priscilla Alden and a cousin to President John Adams, her marriage to a former slave was another source of outrage. Douglass himself wrote:

No man, perhaps, had ever more offended popular prejudice than I had then lately done. I had married a wife. People who had remained silent over the unlawful relations of white slave masters with their colored slave women loudly condemned me for marrying a wife a few shades lighter than myself. They would have had no objection to my marrying a person much darker in complexion than myself, but to marry one much lighter, and of the complexion of my father rather than of that of my mother, was, in the popular eye, a shocking offense, and one for which I was to be ostracized by white and black alike.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a great source of support for Helen. She congratulated the two and wrote:

In defense of the right to… marry whom we please – we might quote some of the basic principles of our government [and] suggest that in some things individual rights to tastes should control…. If a good man from Maryland sees fit to marry a disenfranchised woman from New York, there should be no legal impediments to the union.

Helen was her husband’s intellectual equal, and traveled extensively with him. They lived in Haiti while Douglass served as Minister and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti (1889–1891) under President Benjamin Harrison. In 1892 the Haitian government appointed Douglass as its commissioner to the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition.

Because Elizabeth Cady Stanton had been such a comfort to Helen early in their marriage, Frederick Douglass had remained faithful to the cause of women’s rights. He attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, DC on February 20, 1895. During that meeting, Douglass was brought to the platform and given a standing ovation by the audience.

Shortly after he returned home from that meeting on February 20, 1895, Frederick Douglass suffered a massive heart attack and died at the age of 77. Helen and Frederick had been married for eleven years. His funeral was held at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church where thousands passed by his coffin paying tribute. At the service, Susan B. Anthony gave a eulogy that Stanton had written.

A Memorial to Frederick Douglass

Douglass’ will left Cedar Hill to Helen, but it lacked the number of witnesses needed in bequests of real estate and was ruled invalid. Helen suggested to his children and their spouses that they agree to set Cedar Hill apart as a memorial to their father and deed it to a board of trustees. The children declined, insisting that the estate be sold and the money divided among all the heirs.

With borrowed money, Helen bought the place, and then devoted the rest of her life to planning and establishing the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association. Besides effecting passage of the law incorporating the association, she worked to raise funds to maintain the estate. For eight years, she lectured throughout the northeast.

During the last year of her life, Helen was ill and unable to lecture, as well as discouraged by the falling off of contributions for her cause. She begged the Reverend Francis Grimke not to let her work fall by the wayside in her absence. He suggested that if the mortgage on Cedar Hill should not be paid off in her lifetime, money from the sale of the property should go to two college scholarships in her and Frederick’s names. She agreed, on the condition that the scholarships be in Douglass’ name only.

Helen Pitts Douglass died in 1903 at age 65. Her wish was to be buried on the grounds of Cedar Hill, but that was not allowed. There was no funeral service, and she was quietly buried beside her husband in Rochester.

After Helen’s death, the $5,500 mortgage on Cedar Hill was reduced to $4,000, and the National Association of Colored Women, led by Mary Talbert of Buffalo, New York raised funds to buy Cedar Hill and opened the house to visitors in 1916. Administered by the National Park Service, the Frederick Douglass Memorial Home helps us to better understand the life of the man who is recognized as the father of the civil rights movement.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Helen Pitts Douglass

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

Helen Pitts Douglass was my great great aunt. When she married Douglass, her father insisted her name never be mentioned. In spite of that, Helen’s mother and younger sister maintained contact with Helen.

USA was founded on notions of white supremacy remember Mildred jitter and Richard loving 1958 they had ro leave va as mixed marriages were forbidden we adore Fredrick Douglas and both his for their courage rhey are now up above with the heavenly hosr