One of the First American Feminists and Women’s Rights Activist

Susan B. Anthony played a pivotal role in the 19th century women’s rights and women’s suffrage movements in the United States. Working closely with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Anthony was a primary organizer, lecturer and writer for the movements, especially the first phases of the long struggle for women’s right to vote. She traveled the United States, averaging 75 to 100 speeches per year.

Susan B. Anthony played a pivotal role in the 19th century women’s rights and women’s suffrage movements in the United States. Working closely with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Anthony was a primary organizer, lecturer and writer for the movements, especially the first phases of the long struggle for women’s right to vote. She traveled the United States, averaging 75 to 100 speeches per year.

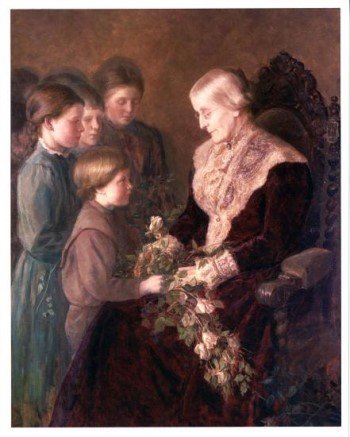

Image: Susan B. Anthony on the Occasion of her 80th Birthday, 1900

By Sarah J. Eddy

Childhood and Early Years

Susan Brownell Anthony was born on February 15, 1820 in Adams, Massachusetts and raised in a Quaker family with long activist traditions. She was the second oldest of seven children born to Daniel and Lucy Read Anthony. Susan was a precocious child, learning to read and write by age three.

In 1826, the Anthony family moved to New York, where Susan attended a local district school, where a teacher refused to teach her long division because of her gender. Upon learning of the weak education she was receiving, her father promptly had her placed in a group home school, where he taught Susan himself.

In 1837, Anthony was sent to a Quaker boarding school in Philadelphia, but she did not stay there long. Her formal education came to an end when her family, like many others, was financially ruined during the Panic of 1837. Their losses were so great that they attempted to sell everything at an auction, but Susan’s uncle restored their belongings to the family.

In 1839, the family moved to Hardscrabble, New York during the economic depression that followed. That same year, Anthony left home to teach and pay off her father’s debts. She taught first at Eunice Kenyon’s Friends’ Seminary, and then at the Canajoharie Academy in 1846, where she rose to become headmistress of the Female Department. Anthony was inspired her to fight for wages equivalent to those of male teachers, since men earned roughly four times more than women for the same duties.

Social Reformer

At age 29 Anthony quit teaching and moved to the family farm in Rochester, New York, where the Anthony family were active in the anti-slavery movement. Anti-slavery Quakers met at their farm almost every Sunday, where they were sometimes joined by Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. Anthony’s brothers Daniel and Merritt were anti-slavery activists in Kansas.

In Rochester, she attended the local Unitarian Church and began to distance herself from the Quakers, in part because she had frequently witnessed instances of hypocritical behavior such as the use of alcohol amongst Quaker preachers. By the 1880s, Anthony was an agnostic.

In 1851, on a street in Seneca Falls, New York Susan B. Anthony was introduced to Elizabeth Cady Stanton by fellow feminist Amelia Bloomer. Later that year Anthony and Stanton organized the first women’s state temperance society in America after Anthony was refused admission to a previous convention on account of her sex.

This experience, and her acquaintance with Stanton, led Anthony to join the women’s rights movement in 1852. Anthony was invited to speak at the third annual National Women’s Rights Convention held in Syracuse, New York in September 1852. She and Matilda Joslyn Gage both made their first public speeches for women’s rights at that convention. Soon after, Anthony dedicated her life to woman suffrage – the right to vote.

Stanton and Anthony remained close friends for the remainder of their lives, but Stanton longed for a broader, more radical women’s rights platform. Stanton, married and mother of several children, served as the writer and idea-person of the two. Anthony never married and was usually the organizer and the one who traveled, gave lectures and bore the brunt of antagonistic public opinion as she attempted to persuade the government that society should treat men and women equally.

Anthony was aggressive and compassionate by nature, with a keen mind and a great ability to inspire. She began to gain notice as a powerful public advocate of women’s rights and as a new and stirring voice for change, participating in every subsequent annual National Women’s Rights Convention and serving as convention president in 1858.

In the era before the Civil War, Anthony took a prominent role in the New York anti-slavery movement. In 1856, recruited by abolitionist Abby Kelley, Anthony became an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society – arranging meetings, making speeches, putting up posters and distributing leaflets. She encountered hostile mobs, armed threats and things thrown at her. She was hung in effigy, and in Syracuse her image was dragged through the streets.

In 1859 Anthony spoke before the state teachers’ conventions in New York and Massachusetts, calling for equal educational opportunities for all regardless of race, and for all schools, colleges, and universities to open their doors to women and people who had been enslaved. She also campaigned for the right of children of people who had been enslaved to be able to attend public schools.

Though women’s rights conventions were not held during the Civil War years, Anthony and Stanton were not idle. In 1863 they and other women’s rights activists organized the Women’s National Loyal League to lobby for an amendment to the US Constitution to abolish slavery. They gathered 400,000 signatures to petition the Congress, significantly assisting in the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment outlawing slavery.

After the war, many who had been active in both women’s rights and anti-slavery activism, wanted to join the two causes. In May 1866, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper spoke at that year’s Women’s Rights Convention, also advocating combining their efforts to win voting rights for women and African Americans. Anthony and other activists founded the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), and the first national meeting was held three weeks later.

Anthony also became more focused on women’s suffrage in her weekly newspaper The Revolution, which she began publishing in 1868. The paper also discussed equal pay for equal work and more liberal divorce laws. Anthony insisted on expensive printing equipment and paid women workers the high wages she thought they deserved. She even got President Andrew Johnson to subscribe before the first issue. However, revenue from advertisements was too low to cover costs, and she sold the paper in 1870.

In 1869, the American Equal Rights Association voted to support the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which granted suffrage to black men, but women were excluded. Anthony questioned why women should support this amendment when black men were no longer supporting women’s voting rights. She also appeared before every Congress from 1869 to 1906, asking for the passage of a suffrage amendment.

In response to the split in the AERA over the Fifteenth Amendment on May 15, 1869 Stanton and Anthony founded the National Woman Suffrage Association, an organization dedicated to gaining women’s suffrage. The rival American Woman Suffrage Association, which supported the Fifteenth Amendment, was founded in November 1869 by Lucy Stone and others.

Ignoring opposition and abuse, Anthony traveled and lectured across the nation for the vote. She also campaigned for women’s labor organizations. She and Stanton were delegates at the 1868 convention of the National Labor Union. In 1870 Anthony formed the Workingwomen’s Central Association, whose purpose was to draw up reports on working conditions and provide educational opportunities for working women.

Anthony boosted the newly-formed women typesetters’ union in The Revolution and tried to establish trade schools for women printers. When printers in New York went on strike, she urged employers to hire women instead, believing this would show that they could do the job as well as men, and therefore prove that they deserved equal pay. Anthony was later expelled from the National Labor Union over this controversy.

A Woman’s Right to Vote

The privileges of citizenship stated in the Fourteenth Amendment contained no gender qualification, and Anthony’s interpretation was that women had been given the constitutional right to vote. She cast a vote in the 1872 Presidential Election in Rochester, New York, writing to Stanton on the night of the election that she had “positively voted the Republican ticket–straight…”

Two weeks later, on November 18, 1872, Susan B. Anthony and three of her sisters were arrested for voting. Anthony refused to pay her streetcar fare to the police station because she was “traveling under protest at the government’s expense.” She was indicted in Albany, and the Rochester District Attorney asked for a change of venue because a jury might be prejudiced in her favor.

The trial gave Anthony the opportunity to spread her arguments to a wider audience than ever before – after her arrest and prior to her trial she undertook an exhaustive speaking tour of all 29 of the towns and villages of Monroe county where her trial was to be held. In her speeches she addressed the question “Is it a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?”

She quoted the Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution, the New York Constitution, James Madison, Thomas Paine and the Supreme Court as proof that women as citizens had a right to vote. She argued that women, always in servitude to man, should be included in the emancipation amendment granting voting privileges to former slaves.

At Anthony’s trial in Canandaigua in 1873, the judge refused to allow Anthony to testify on her own behalf, allowed statements given by her at the time of her arrest to be allowed as “testimony,” explicitly ordered the jury to return a guilty verdict without deliberating, refused to poll the jury afterwards, and read an opinion he had written before the trial even started.

Her sentence was a $100 fine; true to her word in court (“I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty”), Anthony never paid the fine, and an embarrassed US Government took no collection action against her. She petitioned the US Congress to remove the fine in January 1874.

Between 1881 and 1885 Anthony, Stanton, Matilda Joslyn Gage and Ida Husted Harper collaborated on and published the History of Woman Suffrage. The last of four volumes, edited by Anthony and Harper, was published in 1902.

In 1887 the two women’s suffrage organizations merged as the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Anthony campaigned in the West in the 1890s to make sure that territories where women had the vote were not blocked from admission to the Union.

Anthony’s pursuit of alliances with moderate suffragists created tension between herself and more radical suffragists like Stanton. Stanton openly criticized Anthony’s stance, writing that Anthony and Lucy Stone “see suffrage only. They do not see woman’s religious and social bondage.” Anthony responded: “We number over ten thousand women and each one has opinions… and we can only hold them together to work for the ballot by letting alone their whims and prejudices on other subjects!”

Late Years

In the 1890s Anthony raised $50,000 in pledges to ensure the admittance of women to the University of Rochester. In a last-minute effort to meet the deadline she put up the cash value of her life insurance policy. The University was forced to make good its promise and women were admitted for the first time in 1900.

Following her retirement, Anthony remained in Rochester. When asked if women in the United States would ever be given the vote she replied:

It will come, but I shall not see it…It is inevitable. We can no more deny forever the right of self-government to one-half our people than we could keep the Negro forever in bondage. It will not be wrought by the same disrupting forces that freed the slave, but come it will, and I believe within a generation.

Susan B. Anthony died of heart disease and pneumonia on March 13, 1906 at her home on Madison Street in Rochester.

Following her death, the New York State Senate passed a resolution remembering her “unceasing labor, undaunted courage and unselfish devotion to many philanthropic purposes and to the cause of equal political rights for women.”

On August 26, 1920 – fourteen years after Susan B. Anthony’s death – women were given the right to vote by the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, also known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. On November 2, 1920, over eight million American women voted for the first time.

Susan B. Anthony Quote:

There is not the woman born who desires to eat the bread of dependence, no matter whether it be from the hand of father, husband or brother; for any one who does so eat her bread places herself in the power of the person from whom she takes it.

My Favorite Susan B. Anthony Quote

Cautious, careful people, always casting about to preserve their reputation and social standing, never can bring about a reform. Those who are really in earnest must be willing to be anything or nothing in the world’s estimation, and publicly and privately, in season and out, avow their sympathy with despised and persecuted ideas and their advocates, and bear the consequences.

SOURCES

Susan B. Anthony House

Wikipedia: Susan B. Anthony